This report is the second in a TCF series—The Cycle of Scandal at For-Profit Colleges—examining the troubled history of for-profit higher education, from the problems that plagued the post-World War II GI Bill to the reform efforts undertaken by the George H. W. Bush administration.

The return home of thousands of war veterans can bring out the worst in for-profit higher education. The epidemic of fraud and abuse by trade schools that enrolled World War II veterans under the GI Bill, which prompted intense scrutiny by Congress and Presidents Harry S. Truman and Dwight Eisenhower, is a prime example.

For the most part, the reforms Congress had adopted in creating college benefits for veterans of the Korean and Vietnam wars seemed to work, and the 1950s and 1960s were relatively scandal-free.1 In a November 1971 letter, Donald Johnson, President Richard Nixon’s appointee leading the Veterans Administration (VA), went so far as to far to declare that “most of the areas of abuse detected in the earlier World War II program were eliminated.”2

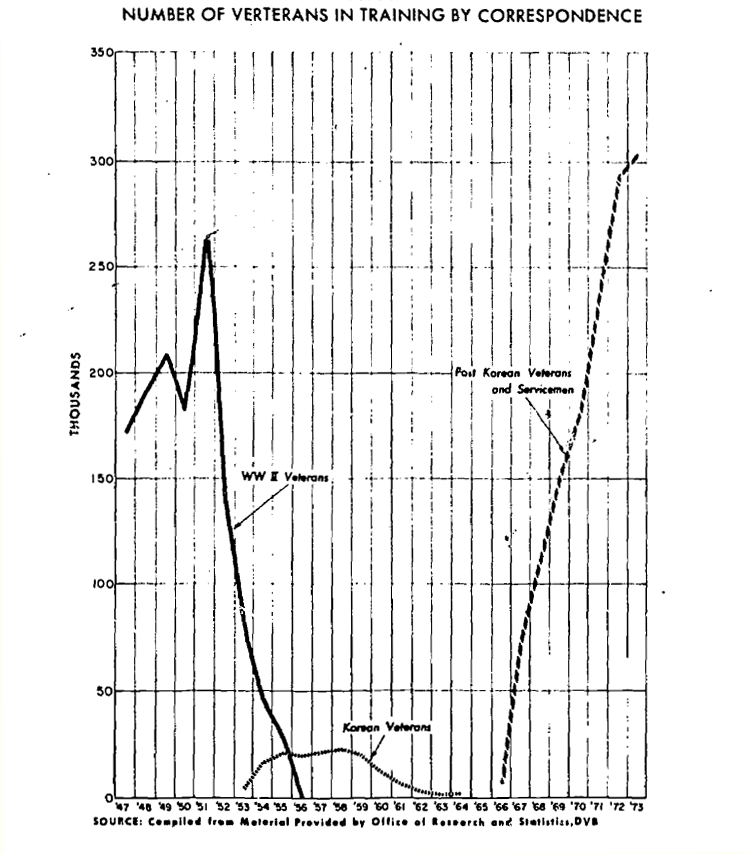

Unfortunately, Johnson’s optimism proved premature. The extension of GI Bill benefits not just to veterans but to active duty servicemen fed a rapid expansion of “correspondence schools,” a more primitive and less interactive version of today’s online education, conducted through the U.S. Mail (see Figure 1). The growth in this for-profit education industry was spurred in large part by the fact that soldiers and veterans could enroll while also holding a full-time job. A report ordered by Congress warned in September 1973 that “private profit making home study schools” were using misleading advertisements and “sophisticated sales techniques” to take advantage of Vietnam veterans and servicemen, who subsequently dropped out at high rates.3 The Trump University scam used similar sales techniques.

Vietnam veterans were not the only ones eligible for federal aid to enroll in these schools. As part of the War on Poverty, President Lyndon Johnson had expanded federal student aid programs to millions of Americans who had not served in the military, creating a new and growing pool of federal dollars for schools to tap. The convergence of these two markets—Vietnam veterans, and the middle- and low-income Americans—created the “perfect storm” for profit-making shenanigans. Harold Orlans, a researcher at the National Academy of Public Administration Foundation observed in 1974 “a pile of money, like a pile of compost, can nourish a lot of worms. That happened when the GI bill provided some $14.5 billion for the education of World War II veterans, and it happened again during the last decade when over $25 billion in student aid was provided under various Federal programs.”4

By the early 1970s, defaults in the relatively new guaranteed student loan program were becoming a national issue. When Terrel Bell, the Nixon and Ford appointee responsible for administering the program, was hauled before Congress in 1976 to explain why his agency was not doing a better job of reducing defaults, he pushed back: “It must be kept in mind that when the floodgates were opened in 1968 to allow virtually every kind of institution operating on an interstate basis to lend under the program—public, private, profit, nonprofit, noncollegiate, and correspondence schools—we had only 50 persons on the staff.”5 The mention of “profit” schools was no accident: by 1975, for-profit schools accounted for most of the defaults in the loan program.6

The Cycle Of Scandal At For-Profit Colleges

Read the series of papers focusing on the repeated for-profit college scandals of the past sixty years.The GOP Reversal on For-Profit Colleges in the George W. Bush Era

When President George H. W. Bush “Cracked Down” on Abuses at For-Profit Colleges

The Reagan Administration’s Campaign to Rein In Predatory For-Profit Colleges

Vietnam Vets and a New Student Loan Program Bring New College Scams

Truman, Eisenhower, and the First GI Bill Scandal

The For-Profit College Story: Scandal, Regulate, Forget, Repeat

The GOP Has a Long History of Cracking Down on “Sham Schools”

Congress Remembered, Then Congress Forgot

In the original proposal for what became the landmark Higher Education Act of 1965, the Johnson Administration included for-profit trade schools as potential participants in the same federally guaranteed student loan program as traditional colleges. Seeking to avoid a repeat of past scandals, Congress objected, and instead created two programs.7 That way, their logic went, the size and parameters of each program could be adjusted separately as needs or problems emerged.8

Just three years later, Congress merged the vocational school loan program into the Higher Education Act. Because this step effectively eliminated any cap on the growth of for-profit colleges financed by federal loans, it was the floodgate-opening that Bell, the top education official to Presidents Nixon, Ford, and Reagan, blamed for the default crisis. As Bell accurately characterized, it proved to be an invitation for excess.

Recruiters at for-profit schools quickly resumed old habits honed under the GI Bill. Access to loans backed by the government, which were called Federally Insured Student Loans (FISL), was like manna from heaven; recruiters could market their schools as financially backed by the federal government, with no risk to private lenders wary of loaning thousands of dollars to students with few assets. As one salesman declared, “I could go down in the ghetto and stand on the corner and enroll all kinds of people if it is free. He doesn’t care if the course is airlines, insurance adjusting, hotel-motel management, or what, if it is free, going to be paid for by the government and you can get him a job. He would have to be crazy not to do this. This is a salesman’s dream.”9 A memo to salesmen from a regional sales manager for Bell and Howell’s vocational schools gave this motivational pep talk: “Get up every morning and say to yourself, ‘I have the product and the way to buy it. I have no money problems because I have FISL . . . I’m going to sell everyone on FISL.’”10

Recruiting new students became so easy that school owners no longer had to worry much about the loss of income from dropouts. As the CEO of LTV Educational Systems explained, “the replacement of a drop-out with a new FISL-financed enrollment became easy, and a new way of life overnight in the business.”11 The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) found that,

the availability of federal loans and grants has worsened the shoddy recruitment, advertising, enrollment practices of the proprietary schools industry. In conjunction with deceptive advertising, high pressure sales tactics and misrepresentations of course difficulty and content, FISL monies have allowed marginal schools to add thousands of students to their rolls without regard for proper career training. Advertisements placed in the media and “canned” sales pitches entice students with claims of federal grants or subsidies. Often the mere mention of the federal government to potential students implies, and is understood as, government inspection and approval of course content and job placement capabilities.12

By 1973, the administrator of the guaranteed loan program at the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) had caught on and warned in internal memos of the rise of “FISL factories.”13 For example, Commercial Trades Institute had just one student with a federal loan in 1970, but had 50,906 such students in 1973. The number at DeVry Institute of Technology rose from 2,663 to 69,934. At Advance Schools, a home-study correspondence school, there was a sixty-seven-fold increase, from 1,209 to 80,891 students with federal loans.14

Major Newspapers Feature Stories of Scam Schools and Defrauded Students

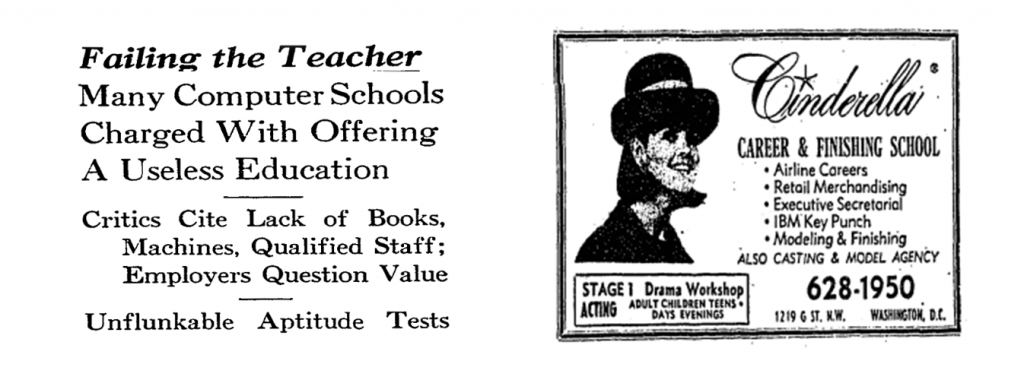

More than a few newspaper reporters went undercover to expose schools by testing the patently phony claims schools made. In a front-page Wall Street Journal June 1970 story headlined “Many Computer Schools Charged with Offering a Useless Education,” reporter Dan Rottenberg took the twelve-question “entrance exam” for the computer programming course at Bryant and Stratton College in Chicago by deliberately answering most of the questions incorrectly. Within a week, he was nonetheless visited at home by a salesman trying to enroll him.15

In 1971, the Washington Post ran a three-part series by Carl Bernstein, who would soon team up with Bob Woodward to break the Watergate story. Bernstein focused on career schools in the Washington, D.C., areas, such as the Cinderella Career and Finishing School, which ran ads to lure young women to enroll on the false promise that they would obtain jobs as airline stewardesses and retail buyers.16 Bernstein found that oversight of the schools was in many cases nonexistent or laughably lax. “In the District of Columbia and at least 20 states,” Bernstein noted, “career schools are operated without any regulation by local law.”17

Bernstein was particularly critical of the federal government’s reliance on accrediting agencies, in which the seal of approval, “accredited by an agency approved by the U.S. Office of Education,” is “bestowed by the same businessmen who operate the private schools, rather than by experts in the vocational fields in which they offer courses.”18 The Washington Post’s editorial page lauded Bernstein’s series, saying that he had “turned up extremely disturbing cases here and elsewhere in which so-called ‘career schools’ have used deceptive advertising and misleading high-pressure sales pitches to entice people into fruitless programs. What’s worse, the articles pointed up an almost total lack of regulation of these schools.”19 (In a piece of historical irony, the Washington Post would later purchase a for-profit college company and editorialize against stronger government regulation.)20 At the time, many conservatives shared the Washington Post’s disenchantment with private accrediting agencies. “As [student aid] programs have grown and proprietary and vocational schools have gained access to them,” Chester Finn Jr, a future Reagan appointee, wrote in 1975, “the accrediting system has failed to organize and conduct itself in ways calculated to prevent the abuses and mishaps that have become endemic.”21

Carl Bernstein’s series was just the start of a slew of newspaper investigations into the for-profit industry. The Boston Globe’s famed “Spotlight” investigative reporting team (later immortalized in the 2015 Oscar-winning film of the same name) conducted a four-month investigation into the quality of education provided by one hundred licensed for-profit schools in Massachusetts. The central conclusion of the March 1974 series was that for-profit career schools had “evolved into a $2.5 billion annual business in the United States largely through the use of high-pressure salesmen, questionable advertising, and the failure of government regulation at all levels.”22

The Spotlight team did a deep-dive investigation into the largest trade school in the state—ITT Technical Institute—and found that the school had been “using misleading advertising and a highly deceptive sales force . . . it has a demonstrably dismal record of training students for careers in their field of study . . . about seven out of ten students who enroll at the school drop out and only half of those who graduate are placed in jobs.”23

According to Globe’s report, ITT’s predatory recruiting practices included sending phony telegrams to 17,000 individuals in “ghetto neighborhoods” such as Boston’s Roxbury, informing them they had been “selected” to take a test at ITT for “our special scholarship program.” The recipients of the phony telegram had simply been selected by their zip code, not based on their achievement or promise and the “special scholarship program” consisted of four scholarships to ITT Technical, only one of which was actually awarded. The Better Business Bureau warned ITT that the massive telegram mailing was unfair, deceptive, and violated state and federal laws. Two weeks later, ITT sent out another round of the same phony telegrams.24

To experience ITT’s recruiting efforts firsthand, three members of the Spotlight team posed as prospective students. They discovered that ITT salesman used the loan application for federal aid “like personal calling cards.” One reporter who sought a guaranteed loan told his ITT salesman he had a high family income that disqualified him from receiving federal student aid, but the salesman wrote down a lower figure on the federal application to maintain the reporter’s eligibility. Another reporter on the Spotlight team deliberately answered more than half of the questions on the qualifying exam for a dental assistant training course incorrectly but was admitted anyway. “You’re pretty smart,” the ITT salesman told her.25 The third reporter applied to be a salesman for ITT and learned that the director of marketing spurred on his salesman with this pithy motto: “Get the asses in the classes.”26

Meanwhile, the Chicago Tribune investigated Chicago-area career schools and correspondence schools. The Chicago Tribune’s series concluded that the industry was “filled with fast-buck operators preying on men and women who believe education is the best way to secure a future. Countless persons seeking to become airline stewardesses, nurses’ aides, TV repairmen, truck drivers, cashiers, and interior decorators are spending $3 billion a year for correspondence and residence school courses. Many are worthless or of questionable value.”27 State records, the Chicago Tribune reported, showed that of the 1,037 students who enrolled in a training program for travel agents in 1974, 686 students dropped out, and only 9 individuals were placed in jobs—a success rate just under 1 percent.

Home-study correspondence schools were especially profitable because of their low overhead costs and the ability to grow quickly. Advance Schools Inc., which called itself the “Cadillac” of correspondence schools, opened in October 1970 and enrolled more than 80,000 students at its peak, with a heavy reliance on FISL loans and GI educational benefits. It filed for bankruptcy in April 1975, leaving behind more than $100 million in government guaranteed student loans outstanding (almost $450 million in today’s dollars).28

In a follow-up to Bernstein’s reporting, a 1974 Washington Post series entitled “The Knowledge Hustlers” found that trade school recruiters, motivated “more by earnings than educational ideals, have gone hunting for customers in the ghetto of Atlanta, Boston and Los Angeles, in Greenville, S.C., and Shreveport, La., in the public housing of Ardmore, Okla., in the food stamp lines of San Antonio, Tx., in the barracks of Army bases in West Germany and even in a halfway house for mental patients in the Pacific Northwest.”29 The companies, the Washington Post series concluded “were exploiting the insured loan program to boost their enrollment revenues. In case after case, the students, whom the program was intended by Congress to benefit, have been the ones to suffer most . . . thousands of young Americans [have been lured] into debt for training opportunities that turned out to be dead ends rather than promising paths to high-paid jobs.”30 Accrediting agencies, in particular, had repeatedly failed “to protect young consumers from being enticed into debt with federally insured student loans by schools that shortchange them, or from wasting their GI Bill benefits on costly, blind-alley correspondence courses. For thousands of veterans and other consumers, accreditation has in fact spelled deception.”31

One feckless accreditor highlighted by the Washington Post was the Association of Independent Colleges and Schools (AICS), which in 1991 became the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools (ACICS). In June 1973, the Office of Education wrote AICS after thirteen of their accredited schools closed within eight months. The shuttered schools had closed “without delivering the educational services for which a large number of student borrowers have paid in advance from proceeds of federally insured students loans.” John Profitt, the director of the Office of Education’s accreditation and institutional eligibility, was clear that the association should have done more to spot the failing career schools. “Questionable recruitment and admissions practices have usually resulted in an alarmingly high dropout rates by these institutions prior to their closure,” Profitt wrote. “Many of these institutions lacked the financial capability to meet required student refund liabilities because of apparent mismanagement.”32

The Washington Post reported that one AICS-accredited school, in San Antonio, would send recruiters to the local welfare office on days when recipients came in to pick up their food stamps. The head of AICS reported in a confidential memo that “a very high percentage of these welfare recipients were migratory farm workers who could only be expected to remain in the area only short periods of time before moving on to another part of the country, automatically producing a dropout that would be very profitable to the institution.”33 The agency’s failure to follow up on signs of abuse is remarkably similar to situations that led the very same accreditor to lose its federal recognition in 2016.34

In 1975, cable TV was in its infancy, and CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC didn’t exist. The three networks were the primary source of national news stories—and in August 1975, for-profit abuses of the FISL program became a bona fide national scandal when the CBS Evening News aired two special reports, two nights in a row, totaling more than fifteen minutes, on abuses by proprietary schools.35

Congress and Multiple Federal Agencies Try to Rein In the Abuses

Most Americans take for granted the existence of consumer protection laws. But when President Nixon took office in 1969, the consumer protection movement was in its infancy. For many businesses, including for-profit colleges, the principle of caveat emptor—buyer beware—was the prevailing maxim. Throughout the 1960s, the proprietary industry joke was that “every school has a refund policy: No refunds.”36 As the consumer protection movement blossomed in the early 1970s, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) emerged for the first time to rein in the excesses of for-profit schools. The FTC’s efforts to regulate for-profit schools “had a profound impact on reforming the proprietary school industry,” according to UCLA education professor Wellford Wilms. “By the early 1970s, public exposures of proprietary schools’ deceptive sales and recruiting practices had become commonplace, underscoring the impotence of state regulatory law and pointing to the need for federal intervention.”37

Reports of abuses at trade schools prompted the FTC, under the direction of Republican stalwarts, to launch an investigation.38 In May 1972, the FTC began what would become an escalating regulatory assault on for-profit schools. That month the Commission issued a “Guide for Private Vocational and Home Study Schools,” identifying practices that the Commission believed were unfair or deceptive.39 In August 1973, the FTC launched a major education campaign—6 percent of the agency’s budget—to warn the public about unethical and illegal practices by vocational schools. The campaign included radio and television spots featuring well-known celebrities, bus posters in thirty-two cities, the distribution of more than 90,000 guidebooks or brochures for consumers, and nearly 70,000 information kits distributed to school counselors.40 Multiple investigations and hearings in six cities led to a remarkable 552-page report from the FTC detailing the methods of predatory schools.41

Concurrent with its consumer protection campaign, the FTC started bringing complaints against for-profit schools. From 1970 to mid-1974, the FTC issued twenty-five complaints against for-profit schools where the commission asserted schools had violated the Federal Trade Commission Act, including four major cases against large for-profit schools. In each case, the FTC alleged that the institutions had “unfairly retained sums obtained from thousands of students through the use of unfair and deceptive practices,” and sought to have the proprietary schools provide restitution for students who were damaged by the “unfair practices and who were unable to obtain employment in the jobs for which training was obtained.”42

Lobbyists for the trade schools dismissed the stories in the media and the FTC findings as anecdotal, blaming students and the U.S. Office of Education for student loan defaults.43 Some members of Congress, many of them Republicans, were not convinced. At a House hearing in July 1974, Alphonzo Bell, a blue-blood GOP congressman from Los Angeles and a former member of the Republican National Committee, labeled the problems a “national scandal,” not “isolated instances of local fraud.”44 The schools had “violated the most minimal standards of decency and professional ethics.” They “lured unsuspecting persons into training courses of dubious value through misleading claims and high-pressure sales tactics. These schools sign up students when there is virtually no possibility they will ever realize the glamorous career objective so eloquently and deceptively sold to them.”45

At the same hearing, Congressman Jerry Pettis, another Republican from Los Angeles, was just as steamed. These “fly-by-night outfits” were, according to Pettis, run by “shrewd manipulators and con artists” interested “only in Federal money for tuition.”46 When a witness from the FTC noted the dozens of cases the agency had filed against individual schools, Congressman Joel Pritchard (R-WA) pleaded for a more comprehensive approach, like legislative recommendations or regulation: “[T]his is not a national disaster but it is certainly a national disgrace. . . . It is hard for me to believe that bringing complaints against 35 or 375 [schools] is really what was needed.”47

Pritchard, a World War II veteran who was familiar with the abuses that had taken place under the first GI Bill, suggested that if the government could not adequately check every school, “the only other way is if you hang a couple of people when they get out of line. That is enforcement and there is no better way to do it and if no one is in jail or in prison today, then you have a lot of people getting away with a lot of bad stuff.”48

Caspar Weinberger, the secretary of health, education, and welfare (who would later become defense secretary in the Reagan administration), saw many students as victims who should not have to repay their loans if the school misled them.

Spurred in part by the FTC’s campaign, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) began to shift its regulatory efforts. While HEW had initially treated rising student loan defaults as largely due to poor collection procedures, federal officials came to believe that in many cases the schools themselves were a bigger problem.49 Using authority Congress had granted it in 1972, the Office of Education began to take action against schools and, by July 1975, the Wall Street Journal reported that 340 had been removed from participation in federal student aid programs. Caspar Weinberger, the secretary of health, education, and welfare (who would later become defense secretary in the Reagan administration), saw many students as victims who should not have to repay their loans if the school misled them. HEW, he said, would recognize “the student’s assertions of a defense and not knowingly attempt to collect from a student when he has a valid defense.”50 Weinberger believed that “the potential for abuse resulting from the rapid increase in the level of federal funds flowing to institutions of higher education . . . required HEW to assume responsibility for administering their operation at a level of detail that in other circumstances would have been entirely inappropriate.”51

In August 1974, just three weeks after the House hearings (and one week after Nixon resigned and Gerald Ford assumed the presidency), the FTC proposed a Trade Regulation Rule for Proprietary Vocational and Home Study Schools. Under the proposed rule, schools would be required to substantiate advertising claims of job placement success. They would have to inform each prospective consumer of the school’s dropout rate. And, if schools made earnings claims about their programs, they would have to prominently disclose the job placement rates and salary levels of their students.52

Congress, meanwhile, in a law that expanded GI Bill benefits for Vietnam veterans, banned schools from education and training programs that used recruiting or advertising which was “erroneous, deceptive, or misleading either by actual statement, omission, or intimation.”53 (The bill’s cost drew a veto from President Gerald Ford that was subsequently overridden by Congress).

In October, HEW proposed new rules governing the student loan program. Finalized in February 1975, the rules required that all institutions provide information disclosures to students before they enrolled, and a “fair and equitable refund” to students who changed their minds about attending. The regulations further specified that, for prospective students at vocational schools, institutions must disclose information about a student’s employment prospects in their field of training.54

Terrel Bell, the education commissioner, explained, “I personally question the soundness of an institution whose existence is totally derived from signing up students who qualify for Federal aid.”

Perhaps most striking, the HEW regulations allowed the commissioner of education to review the continued eligibility for student aid of any school that became too reliant on federal loans, a figure pegged at 60 percent of the enrolled students. In a speech entitled “It’s Time to Protect Education Consumers Too,” Terrel Bell, the education commissioner, explained, “I personally question the soundness of an institution whose existence is totally derived from signing up students who qualify for Federal aid.”55 Conservatives generally applauded the Ford administration’s new regulations. Chester Finn, Jr., a researcher who would go on to be a senior appointee at the Department of Education in the Reagan administration, said the rules “set reasonable standards for the government to employ against the political, fiscal, and human costs of fly-by-night institutions, false advertising, overly zealous recruiting, and shoddy teaching. Indeed, one might well wonder why they were so long in coming.”56

The Veterans Administration got tougher too. It was the VA’s view that schools that ran completely off of federal aid represented a hazard to veterans and to taxpayers. A requirement that prohibited more than 85 percent veterans in a program had helped to prevent abuse, but it was being undermined by the newer federal aid programs to non-veterans. The VA administrator asked Congress to require schools to show that some students—at least 15 percent—pay for programs receiving GI Bill funds without federal aid of any type. “It is our position that, if an institution of higher learning cannot attract sufficient nonveteran and nonsubsidized students to its programs it presents a great potential for abuse of our GI educational programs.”57 Congress adopted the change along with others, agreeing the reforms were needed to “weed out those institutions who could survive only by the heavy influx of Federal payments.”58

As a result, default rates dropped, and, in a 1982 retrospective on his time at HEW, Caspar Weinberger declared victory: “History apparently had judged our efforts to limit GSLP [guaranteed student loan program] abuses to be successful.”59 The reforms, however, did not stick. Loopholes in the HEW regulations, as well as lawsuits and lobbying by the industry, soon undermined the new federal laws and regulations. Abuses of both the student loan program and the Pell Grant program resurfaced with a vengeance just a few years later during the administration of a Republican icon, President Ronald Reagan.

Timeline of For-Profit Higher Education

Scroll through the below timeline to view the history of for-profit higher education.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this report stated that ACICS lost federal recognition in 2015, when this actually occurred in 2016. The report was updated to reflect this correction on March 14, 2017.

Notes

- Educational Benefits Available for Returning Vietnam Era Veterans, Part I, Hearings before the Subcommittee on Readjustment, Education, and Employment, Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, 92nd Cong., 2nd Sess., March 23, 1972, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtbHo3N0tya29uRjA/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid., 51.

- James Bowman et al., “Educational Assistance to Veterans: A Comparative Study of Three GI Bills,” Educational Testing Service, September 1973, reprinted in Final Report on Educational Assistance to Veterans: A Comparative Study of Three G.I. Bills, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, U.S. Senate, Senate Committee Print No. 18, September 20, 1973, 93rd Cong., 1st sess., 171, 181, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtamhSMmRzcURGdTg/view?usp=sharing.

- Testimony of Harold Orlans in Proprietary Vocational Schools, Special Studies Subcommittee of the House Committee on Government Operations, 93rd Cong, 2nd Sess., July 1974, 56, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUteWUtOUtva0NVUVk/view?usp=sharing.

- Terrel Bell (who later became President Reagan’s education secretary), in “Guaranteed Student Loan Program,” Hearings before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations, United States Senate, Part I, 1976, 282, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtZTVLVmJHeE42MFE/view?usp=sharing.

- Loans to borrowers from for-profit schools accounted for 88 percent of all delinquent funds paid. Proprietary Vocational and Home Study Schools, Final Report to the Federal Trade Commission and Proposed Trade Regulation Rule, Part II, Federal Trade Commission, December 10, 1976, 510, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtQUhtUXRmOTFzZFk/view?usp=sharing.

- Charlotte J. Fraas, “Proprietary Schools and Student Financial Aid Programs: Background and Policy Issues,” Congressional Research Service, 90-427 EPW, Aug. 31, 1990, p. CRS-51. When Congressman William Ford (D-Michigan), the future chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee arrived in Washington after being elected in 1964, he found that Congress was still “broiling with anger” about the misuse of federal student aid dollars. The anger, Ford recalled, “remained from the period of the much-publicized abuses of the GI bill.” Hearings on the Reauthorization of The Higher Education Act of 1965: Program Integrity, House Committee on Education and Labor, Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education, 102nd Cong., 1st Sess., Serial No. 102-39, May 30, 1991, 427, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtTmxZMF9fa2JPb3c/view?usp=sharing.

- The vocational program began much smaller. The National Vocational Student Loan Insurance Act of 1965 authorized insurance for an estimated $19 million in loans, according to President Johnson’s signing statement available at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=27327. The Higher Education Act, P.L. 89-329, called for loan guarantees up to $1.4 billion.

- Larry Van Dyne, “The ‘FISL Factories,’” The Chronicle of Higher Education 10, no. 19, August 4, 1975, 5. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtSzVERHVsS3BhMm8/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid, 4.

- Quoted in Proprietary Vocational and Home Study Schools, Final Report to the Federal Trade Commission and Proposed Trade Regulation Rule, Federal Trade Commission, December 10, 1976, 157, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtQUhtUXRmOTFzZFk/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid., 300–01.

- Quoted in Larry Van Dyne, “The ‘FISL Factories,’” The Chronicle of Higher Education, August 4, 1975, 4. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtSzVERHVsS3BhMm8/view?usp=sharing.

- Proprietary Vocational and Home Study Schools, Final Report to the Federal Trade Commission and Proposed Trade Regulation Rule, Federal Trade Commission, December 10, 1976, 298, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtQUhtUXRmOTFzZFk/view?usp=sharing.

- Dan Rottenberg, “Many Computer Schools Charged with Offering a Useless Education,” Wall Street Journal, June 10, 1970, 1. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtc1ctUDBkb1dXa3M/view?usp=sharing.

- Carl Bernstein, “’Deceptive’ Career School Ads Cited by FTC,” Washington Post, July 14, 1971, pp. C1, C3, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtTHpkWVB5a2YwdU0/view?usp=sharing. Bernstein reported that an FTC investigation of Cinderella had found that “central to [the school’s] mode of operation is the promise of the availability of jobs and the holding out of nonexistent jobs to prospective students for the sole purpose of enrolling them.”

- Carl Bernstein, “Hard Sell on Job Training,” Washington Post, July 12, 1971, A1, A3, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtSTNqY3M2Y0JxNFU/view?usp=sharing.

- Carl Bernstein, “Career Schools Find Haven in Washington,” Washington Post, July 15, 1971, B1, B2, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtSjN6Z2NVOGVZWGM/view?usp=sharing.

- “Career Schools: Broken Rules, Shattered Hopes,” Washington Post, October 7, 1971, A22, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtWGY1ZGVLN094dWc/view?usp=sharing.

- “How to Discourage College Students,” Washington Post, Aug. 22, 2010, A14, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/08/21/AR2010082102468.html. The Washington Post’s editorial prominently disclosed that “Readers should know that we have a conflict of interest regarding this subject. The Washington Post Co., which owns the Post newspaper and washingtonpost.com, also owns Kaplan University and other for-profit schools of higher education that, according to company officials, could be harmed by the proposed regulations.” The Post’s ombudsman suggested in November 2010 that the paper expand its coverage of allegations against Kaplan. Andrew Alexander, “Post Needs to Beef Up Its Coverage of Allegations against Kaplan,” Washington Post, November 19, 2010. Nine days earlier, the New York Times had run an extensive front-page story on the allegations against Kaplan. See Tamar Lewin, “Scrutiny and Suits Take a Toll On For-Profit College Company,“ New York Times, November 10, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/10/education/10kaplan.html.

- Chester Finn Jr., “In Washington We Trust, Federalism and the Universities: The Balance Shifts,“ Change 7, no. 10 (Winter 1975/76): 26, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtYlM1bW1PTXVVYWc/view?usp=sharing.

- Spotlight Team, “Many Career Schools Turn Education Into a Fast-Buck,“ Boston Globe, March 26, 1974, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtcTh1QXVmaVd4eTg/view?usp=sharing.

- Spotlight Team, “ITT Tech watches profit, puts quality training in back row,” Boston Globe, March 26, 1974. The complete Spotlight Team series from the Boston Globe, which ran from March 25 to April 1, 1974, was reprinted in the Congressional Record, Senate, April 4, 1974, S5235-S5249, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtcW5yd1hDeVZaa2s/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid.

- Spotlight Team, “ITT Health-Assistant Courses Prove Costly, Bitter Lessons,” Boston Globe, March 26, 1974, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtX3kxMVNSUkRHenM/view?usp=sharing.

- Spotlight Team, “ITT Tech watches profit, puts quality training in back row,” Boston Globe, March 26, 1974, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtcW5yd1hDeVZaa2s/view?usp=sharing.

- Tribune Task Force Report, “Career schools—results seldom equal promise,” Chicago Tribune, June 8, 1975, 1, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtUGlzYURKdDNla3c/view?usp=sharing.

- Mike Tharp, “Charges of Fraud Hit Student-Loan Program Backed by Government,” Wall Street Journal, June 30, 1975, 1, 9, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtZWVqWUF3VHJoZGs/view?usp=sharing.

- Eric Wentworth, “Profit-Making Schools: Deception and Exploitation Charged,” First in the series, “The Knowledge Hustlers,” Washington Post, June 23, 1974, A1, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtdElVU3d0MFBEbjA/view?usp=sharing.

- Eric Wentworth, “Folding Schools Increase Loan Defaults,” Second in a series, “The Knowledge Hustlers,” Washington Post, June 24, 1974, A1, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtOWdFMUZ3eEl2ZXc/view?usp=sharing.

- Eric Wentworth, “For Thousands, Accreditation Has Spelled Deception,” Last in a series, “The Knowledge Hustlers,” Washington Post, June 26, 1974, A14, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtOW85a3VLSmx0dkU/view?usp=sharing.

- Wentworth, “Folding Schools Increase Loan Defaults,”A1, A14, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtOWdFMUZ3eEl2ZXc/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid.

- Paul Fain, “Education Secretary Drops Recognition of Accreditor,” Inside Higher Ed, December 13, 2016, https://www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2016/12/13/education-secretary-drops-recognition-accreditor.

- CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite, August 18–19, 1975. Roger Mudd substituted as anchor for Cronkite for both broadcasts. The two Special Reports on for-profit schools were reported by Sharron Lovejoy, with an assist from Bernard Kalb.

- Quoted in Wellford W. Wilms, “Proprietary Schools and Student Financial Aid,” The Journal of Student Financial Aid 13, no. 2 (Spring 1983): 9, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtVDV3WFpkZTVKcnM/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid., 8.

- The chairman of the FTC was Lewis Engman, a Nixon loyalist who had been the assistant director of Nixon’s White House Domestic Policy Council and subsequently became head of the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association. Nixon White House aide Elizabeth Hanford, who would soon marry GOP Senator Bob Dole and go on herself to become a GOP senator, was one of the five FTC commissioners.

- See testimony of Joan Z. Bernstein, deputy director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection at the FTC, in Proprietary Vocational Schools, Hearings of the Special Studies Subcommittee of the House Committee on Government Operations, July 1974, 17, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUteWUtOUtva0NVUVk/view?usp=sharing.

- The celebrities included Della Reese, an African-American singer-actress-talk show host, and Raymond Burr, known for portraying District Attorney Perry Mason in an eponymous long-running television series. Ibid., 42–44.

- Proprietary Vocational and Home Study Schools, Final Report to the Federal Trade Commission and Proposed Trade Regulation Rule, Federal Trade Commission, December 10, 1976, 21, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtQUhtUXRmOTFzZFk/view?usp=sharing.

- Proprietary Vocational Schools, Hearings of the Special Studies Subcommittee of the House Committee on Government Operations, July 1974, 42, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUteWUtOUtva0NVUVk/view?usp=sharing.

- Many industry advocates bitterly resented the FTC campaign and vowed to lobby Congress to undo the FTC’s actions. At the July 1974 House hearing, Joseph Clark, president of the National Association of State Administrators and Supervisors of Private Schools, attacked the “generals“ at the FTC for shooting expanding “dum-dum bullets” at for-profit schools by employing “well-known personalities whose words explode in the minds of the consumer, killing unfortunately, that’s person attempt to obtain a good education.” Ibid., 82. Clark also warned the chairman of the House subcommittee, Representative Floyd Hicks (D-WA), that “I’m speaking right now for 42 states in the nation when I’m telling you they are so upset . . . what’s going to happen is that at some point we are going to start fighting them in Congress and the Senate. And when you stop and multiply 42 States by the number of Congressmen and Senators we have, I don’t think the Federal Trade Commission wants that kind of a fight.” Ibid, 112, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUteWUtOUtva0NVUVk/view?usp=sharing.

- Proprietary Vocational Schools, Special Studies Subcommittee of the House Committee on Government Operations, July 1974, 3, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUteWUtOUtva0NVUVk/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid., 4.

- Ibid., 8.

- Pritchard had asked, “Have you sent up any legislation or did you bring forth any legislation that would have given you either more clout or some type of an answer to this problem?“ Proprietary Vocational Schools, Special Studies Subcommittee of the House Committee on Government Operations, July 1974, 44, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUteWUtOUtva0NVUVk/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid., 49.

- In 1975, the U.S. Office of Education went to the extraordinary lengths of awarding a research contract to identify a “taxonomy of practices for which there could be general agreement that ‘this is clearly abusive.’” Researchers at the American Institutes of Research (AIR) performed a literature search of abusive practices by postsecondary institutions and reviewed all 630 complaints USOE had received from students from 1969 to July 1975 about their postsecondary education. In the contract award, USOE had not limited AIR’s research just to abuses committed by proprietary schools. But AIR researchers discovered that all of the 630 complaints that USOE had received in the previous six years involved proprietary schools. Based on its analysis, AIR compiled a list of 14 practices of institutional abuse similar to those identified by the Teague Commission more than twenty years earlier—inequitable refund policies, misleading recruiting and admission practices, untrue or misleading advertising, lack of adequate job placement services, lack of adequate financial stability, etc. See Steven M. Jung, Jack A. Hamilton, et. al, “Study Design and Analysis Plan: Improving the Consumer Protection Function in Postsecondary Education,“ October 21, 1975, American Institutes for Research, AIR-52800-10/75-TR, 10, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtNW5CdVhaTElQQVk/view?usp=sharing.

- Mike Tharp, “Charges of Fraud Hit Student-Loan Program Backed by Government,“ Wall Street Journal, June 30, 1975, 1, 9, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtZWVqWUF3VHJoZGs/view?usp=sharing.

- Caspar W. Weinberger, “Reflections on the Seventies,“ Journal of College and University Law 8, no. 4 (1981–82): 452-453, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtV0phX2c5bFBYTmM/view?usp=sharing.

- The proposed rule, initially released on August 15, 1974 (Federal Register 39, no. 159 [August 15, 1974]: 29385), was reissued in May 1975 due to changes Congress had made with respect to an unrelated issue. “Proprietary Vocational and Home Study Schools,“ Federal Register 43, no. 250 (December 28, 1978): 60819, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtQUhtUXRmOTFzZFk/view?usp=sharing.

- Public Law 93-508, December 3, 1974. With the support of the Nixon administration, Congress also added a requirement in 1972 that veterans and active-duty servicemen had to pay 10 percent of the tab for correspondence courses out of their own pocket. The 10 percent requirement was designed to give GIs a financial stake in their choice of correspondence courses and to encourage them to think through their job training objectives. See the November 27, 1971 letter from Veterans’ Administration administrator Donald Johnson to Vice President Spiro Agnew, reprinted in Educational Benefits Available for Returning Vietnam Era Veterans, Part I, Subcommittee on Readjustment, Education, and Employment of the Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, 92nd. Cong., 2nd Sess., March 23, 1972, 191, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtbHo3N0tya29uRjA/view?usp=sharing.

- “Chapter I—Office of Education, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Part 177—Federal, State and Private Programs of Low-Interest Loans to Students in Institutions,“ Federal Register 40, no. 32 (February 20, 1975):7596, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7adHdBE6w3mbGp3ZHRncW1HdzQ/view?usp=sharing. Programs that prepared students for a particular vocation, trade, or career field were to provide prospective students with information on “the employment of students enrolled in such courses,” including “data regarding the average starting salary for previously enrolled students entering positions of employment for which the courses of study offered by the institution are intended as preparation and the percentage of such students who obtained employment in such positions.” The school’s information was to be “based on the most recently available data. If the institution, after reasonable effort, cannot obtain statistically meaningful data regarding its own students, it may use the most recent comparable regional or national data.”

- “It’s Time to Protect Education Consumers Too,” remarks of U.S. Commissioner of Education Terrel H. Bell to the Statewide Higher Education Executive Officers, April 24, 1975, 5. Bell noted that “when there is rapid growth in any sector, there is a danger of malpractice. And, as much as we would like to attribute beneficence to the world of education, it, too, has its charlatans—the seekers of the fast buck.” http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED108554.pdf.

- Chester Finn Jr., “In Washington We Trust, Federalism and the Universities: The Balance Shifts,“ Change 7, no. 10 (Winter 1975/1976): 25–26, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtYlM1bW1PTXVVYWc/view?usp=sharing.

- The VA administrator, Donald Johnson, is quoted in Senate Rep. No. 1243, 94th Cong., 2nd Sess. 1976, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtVS1XUnVCdHVCWlU/view?usp=sharing, 89.

- Ibid. The industry sued to stop the 85–15 rule, arguing among other things that it denied veterans equal protection of the law since the 85–15 rule didn’t apply to non-veterans, whose education could otherwise be subsidized by the federal government. In 1978, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected that argument and upheld the requirement. It found that the history of the G.I. Bill “revealed a need for legislation that would minimize the risk that veterans’ benefits would be wasted on educational programs of little value. It was not irrational for Congress to conclude that restricting benefits to established courses that have attracted a substantial number of students whose education are not being subsidized would be useful in accomplishing this objective and ‘prevent charlatans from grabbing the veterans’ education money.’”Cleland v. National College of Business, 435 U.S. 213, 1978, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/435/213/case.html.

- Caspar W. Weinberger, “Reflection on the Seventies,“ Journal of College and University Law 8, no. 4 (1981–82), 456, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtV0phX2c5bFBYTmM/view?usp=sharing.