We are making significant progress in early childhood education but still have a long way to go. Over the past decade, new research in neuroscience on the benefits of high-quality early learning experiences has been met with increased state and federal investments in early childhood policies. Funding for state pre-K programs has doubled in the past ten years, and the federal government has also made new investments through the Preschool Development Grants and the Race to the Top–Early Learning Challenge. President Obama has also announced ambitious proposals for expanding early education and child care in his 2013, 2014, and 2015 State of the Union addresses—although the these plans have yet to find substantial political traction in Congress.1 And as we approach the 2016 presidential election, early childhood policy is poised to be a central issue of debate.

But this increase in public spending—and the benefits that accrue from it—is not distributed among all American families. While there’s growing political consensus that investing in high-quality early care and learning for low-income children is worthwhile, there is less agreement about the extent to which middle-class families should be included in public early childhood programs. High-quality early childhood programs are expensive because they invest in their workforce through wages, benefits, and training; include low adult-to-student ratios; and implement research-based curricula. President Obama’s Preschool for All initiative would cost $66 billion over ten years to expand states’ pre-K coverage to families earning up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level.2 Those who oppose expanding programs beyond low-income families argue that we do not have enough evidence that pre-K and child care benefit middle-class families to warrant an expensive investment.3

These arguments, however, are out of date. New research has revealed the ways that high-quality early care and education benefit both middle-class children and middle-class parents. Middle-class children attending high-quality early learning programs show improved cognitive outcomes and increased future earnings. Data on parent employment, preschool enrollment, and the cost of child care also make it clear that middle-class families too often lack access to the high-quality early childhood programs that parents and children need to thrive.

In this issue brief, we outline the research on the benefits of early care and learning for middle-class families—looking at the educational benefits for children, as well as the workforce benefits for parents. And we present policy solutions for states and the federal government to expand access to high-quality early care and learning for both middle- and low-income families, through universal pre-K and guaranteed child care subsidies.

The Educational Benefits of High-Quality Early Care and Education for Middle-Class Children

A large and consistent body of research shows that high-quality early learning programs can have a huge impact on the future success of low-income children—improving learning and development, reducing delinquency and criminal activity, boosting health, and increasing future employment and earnings.4 But what about middle-class children? Do they benefit as well?

Studies have found that the first five years of children’s lives are critical to their ability to learn social and emotional skills, as well as for setting them up to be good students and citizens later in life.5 This is true regardless of family income, and the early care experiences of children play an important role in shaping their brains. Historically, however, most research on early education has focused on low-income children.

It is only recently that we have more evidence on the benefits of early care for middle-class children. Not all of the child care and parenting programs that have been very successful at improving outcomes for low-income children have shown the same results for middle-class children.6 We do have studies, however, that show that when three- and four-year-olds are enrolled in high-quality pre-K—the programs that have been most studied—that middle-class children experience educational and economic boosts almost as large as those seen for low-income children. Furthermore, when middle-class and low-income children have the chance to attend preschool together, both groups benefit from the increased diversity in the classroom. Unfortunately, data on preschool attendance and the quality of the programs children actually attend shows that, for many middle-class children, the benefits of high-quality pre-K are currently out of reach.

Improved Learning Outcomes

In Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Boston, Massachusetts, two cities with universal pre-K programs that have been recognized as high quality, both middle- and low-income children have shown increased learning outcomes as a result of participating in the programs. In Tulsa, middle-income children who attended pre-K entered kindergarten seven months ahead of their nonparticipating peers in pre-reading skills. (Low-income children benefited even more, entering kindergarten ten to eleven months ahead of their peers; see Figure 1.)7 Likewise, in Boston, middle-class children experienced large gains in literacy and math skills as a result of attending pre-K—with low-income children showing similar gains as well as increased social-emotional skills related to self-regulation and attention.8

Figure 1

Increased Future Earnings

Like low-income children, middle-class children also stand to benefit from pre-K much further down the road, in the form of increased adult earnings. Economist Timothy Bartik of the Upjohn Institute calculates that middle-class children experience a boost in future earnings from attending high-quality pre-K that is nearly as great as that of low-income children in dollar amount.9 (See Figure 2. Since low-income children start with a lower baseline of expected future earnings, pre-K still has the effect of reducing economic inequality; the expected boost in future earnings for low-income children represents a 10 percent increase, compared to a 5 percent increase for middle-class children.)

Figure 2

Added Benefits of Diverse Classrooms

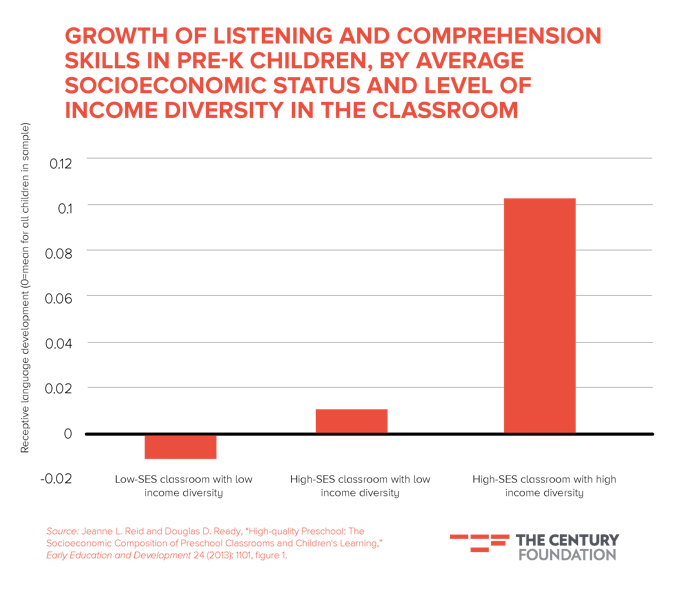

Making public pre-K programs accessible to middle-income children also creates the added benefit of opportunities for socioeconomically diverse preschool classrooms, which have been shown to improve children’s learning. In a 2013 study of pre-K programs in eleven states, classrooms with a mix of lower- and higher-income children showed greater positive effects on children’s listening and comprehension skills than classrooms with similar average socioeconomic status (SES) but less income diversity.10 (See Figure 3.) That means that it is a benefit to both middle- and low-income children to attend programs in which children of different economic backgrounds learn side by side—and that is something that is not likely to happen in public pre-K programs that are restricted to low-income children, as most currently are, or in private pre-K programs, which are typically out of reach for low-income families.

Figure 3

Need for Greater Access and High-Quality Programs

Despite the evidence showing the benefits of high-quality pre-K for middle-income children, middle-class preschool attendance lags behind that of high-income children. Among children in families with middle socioeconomic status, just 54 percent of children attend preschool during the year before kindergarten, ahead of their low-SES peers but still well behind high-SES peers. (See Figure 4.) Furthermore, among those children that do enroll in preschool, middle-SES children are less likely than both low-SES and high-SES peers to be enrolled in high-quality programs. (See Figure 5.) Within the current system of an often costly private market and public programs that mostly target low-income children, many middle-class children are left without access to high-quality early education.

Figure 4

Figure 5

The Workforce Benefits of Affordable Early Care and Education for Middle-Class Parents

High-quality early care is not only about advancing children’s learning, but also about supporting families so that parents can work. Most children today grow up in families without a stay-at-home parent. The cost of child care and preschool is a significant financial burden even for middle-class families, and research suggests that making child care and early education more available to middle-class parents makes it more likely that they will be able to work.

Rising Parent Workforce Participation

In 1965, six out of ten families contained at least one parent who did not work. Fifty years later, that ratio has flipped: in six out of ten families today, all parents are working.11 Among families with children under age six, less than one in three families fits the stereotypical model of a married couple with one breadwinner. (See Figure 6.) Increasingly, families across the income spectrum have all parents in the workforce and are in need of child care.

Figure 6

High Cost of Early Care and Education

At the same time that more parents are working, child care costs in the United States are on the rise.12 The current costs of child care present a financial challenge not only to low-income families but even to middle-income families. In twenty-three states and the District of Columbia, the cost of child care for a four-year-old is greater than 10 percent of the median family income for a married couple with children, and the costs of care for an infant are considerably higher.13 In many states, the cost of care for one four-year-old is greater than the cost of in-state college tuition, and not much less than average housing costs. (See Table 1.) A new study from the Economic Policy Institute shows that in thirty-three states and the District of Columbia, the average cost of infant care exceeds in-state tuition at four-year public colleges.14 Factor multiple children into the picture, and it is not hard to see how it is a struggle to afford child care, even for families earning above the median income. Improving access to affordable child care, therefore, can have a big effect on the employment and economic opportunities available to middle-class parents. In fact, one study found that the cost and stability of child care had a larger effect on middle-income mothers’ workforce participation than that of either low- or high-income mothers.15

Table 1

Public Policy Solutions

Taken together, the educational research and workforce evidence form a strong case for bold public investment in early childhood programs, expanding access to include more middle-income families alongside low-income families. A combination of two policies—universal pre-K and expanded child care subsidies—would lay a strong foundation for our children.

Universal Pre-K

Currently, only eighteen states and the District of Columbia have public pre-K programs with universal eligibility (without income or other risk factor requirements), and in most of these cases, the programs do not have the capacity to serve all eligible children. Only the District of Columbia, Florida, Oklahoma, and Vermont have state pre-K programs with universal access and more than 70 percent of four-year-olds enrolled. (And of those, only the District of Columbia and Oklahoma have programs that score high on quality rankings.)16

State policymakers should create or expand universal pre-K for all three- and four-year-olds. Ensuring quality is essential—and states should take lessons from places such as the District of Columbia and Oklahoma that have expanded access while promoting high standards. Furthermore, as part of the focus on quality, these programs should encourage socioeconomically diverse enrollment at the classroom level in their recruitment and enrollment processes.

The federal government should help to support this work through a significant investment and by partnering with states. Recent federal proposals for expanding pre-K—both President Obama’s Preschool for All initiative and pre-K legislation introduced in Congress—focus on expanding eligibility for state pre-K to families making up to 200 percent of the poverty line. However, given the benefits of pre-K for middle-class children, and the benefits that socioeconomically diverse classrooms have for all children, federal programs should include added incentives for states that create truly universal access, with no income cap.

Child Care Subsidies

Despite the importance of a significant federal and state investment in child care, today the investment is fragmented and woefully inadequate. Low-income families are eligible for child care subsidies through the Child Care Development Block Grant and middle-class families are eligible for Child Care and Dependent Tax Credits.17 However, only about one in six eligible low-income children receive subsidies, largely because of inadequate funding.18 In addition, too often families cannot find care that meets their needs, particularly with so many families working nontraditional hours. The average middle-class family who receives the tax credit gets about $560—a drop in the bucket compared to the average cost of $11,000 per child per year for center-based care.19

We need high-quality, flexible care for all families—care that is affordable while also valuing the work of caregivers. The National Campaign Make It Work has proposed a plan for child care assistance that would make sure that high-quality child care costs no more than 10 percent of a family’s income, and that child care providers earn a wage of at least $15 an hour.20 All families with children aged twelve or younger and earning up to twice the median income in their state would be eligible for the subsidies. Such a guarantee would provide middle- and low-income families access to the same child care assistance program—one that truly helps them cover the cost of high-quality care of their choosing.

The plan would require significant federal funding—large enough to serve both middle-class and low-income families, and to keep costs affordable for families while promoting high-quality care with decent wages for child care providers. Under the proposed plan, the number of children receiving assistance, including school-age kids who need before- and after-school care, would increase from just 1.4 million children today to approximately 26 million. Meanwhile, the people providing care for those children would receive a boost in earnings that values the important work they do. Together, these investments in our children’s healthy development, and in their parents’ ability to go to work and earn a decent living, hold the promise of great dividends.

Conclusion

All children deserve the opportunity to succeed, which includes ensuring they are cared for in safe, nurturing, educational environments, and have the opportunity to go to kindergarten ready to learn. But today, too many working parents do not have those options for their children.

Much of early childhood policy at the federal and state level focuses on how to divide existing funding for maximum effect. With limited resources, it makes sense that most early childhood programs so far have focused on serving low-income families. And yet current funding still leaves programs like Head Start and the Child Care Development Block Grant unable to serve all qualifying families, while also forcing most middle-class families to fend for themselves, with few affordable options available.

The premise of this scarcity-based approach to funding early childhood investments is flawed. Instead of fighting over limited resources, we must create a bigger pie. It is time to make the significant investments needed to make affordable, high-quality care and education—with corresponding investments in caregivers and teachers—a reality for all families.

Notes

-

1. Jessica Grose, “Obama Declares Child Care ‘a Must Have,’” Slate, January 20, 2015, http://www.slate.com/blogs/xx_factor/2015/01/20/state_of_the_union_president_obama_declares_childcare_a_must_have_not_a.html.

2. Travis Waldron, “UPDATE: Obama Budget Includes $75 Billion to Fund ‘Preschool for All’ Initiative,” ThinkProgress, April 10, 2013, http://thinkprogress.org/education/2013/04/10/1846061/obama-budget-includes-66-billion-to-fund-preschool-for-all-initiative/.

3. See, e.g., David J. Armor, “The Basis for Expanding Pre-K Is Weak,” Education Week, January 2, 2015, http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2015/01/08/the-basis-for-expanding-pre-k-is-weak.html?r=905073761.

4. W. Steven Barnett, Preschool Education and Its Lasting Effects: Research and Policy Implications (Boulder and Tempe, Ariz.: Education and the Public Interest Centers and Education Policy Research Unit, 2008), http://nieer.org/resources/research/PreschoolLastingEffects.pdf.

5. First Five Years Fund, “Brain Development,” (n.d.), http://ffyf.org/why-it-matters/brain-development/ (accessed October 5, 2015).

6. Timothy J. Bartik, From Preschool to Prosperity: The Economic Payoff to Early Childhood Education (Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2014), 44.

7. William T. Gormley, Jr., Karin Kitchens, and Shirley Adelstein, Do Middle-Class Families Benefit from High-Quality Pre-K? (Washington, D.C.: Center for Research on Children in the U.S., July 2013), 2, http://fcd-us.org/sites/default/files/Policy%20Brief_draft_071613_0.pdf.

8. Christina Weiland and Hirokazu Yoshikawa, “Impacts of a Prekindergarten Program on Children’s Mathematics, Language, Literacy, Executive Function, and Emotional Skills,” Child Development 84, no. 6 (November/December 2013): 2112–30.

9. Bartik, From Preschool to Prosperity, 47, table 5.1.

10. Jeanne L. Reid and Douglas D. Ready, “High-quality Preschool: The Socio-economic Composition of Preschool Classrooms and Children’s Learning,” Early Education and Development 24, no. 8 (2013): 1101, fig. 1.

11. Council of Economic Advisers, Nine Facts about American Families and Work (Washington, D.C.: Executive Office of the President of the United States, June 2014), 11, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/nine_facts_about_family_and_work_real_final.pdf.

12. Drew Desilver, “Rising Cost of Child Care May Help Explain Recent Increase in Stay-at-home Moms,” Pew Research Center, Fact Tank: News in the Numbers, April 8, 2014, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/04/08/rising-cost-of-child-care-may-help-explain-increase-in-stay-at-home-moms/.

13. Parents and the High Cost of Child Care: 2014 Report (Arlington, Va.: Child Care Aware of America, 2014), 20.

14. Elise Gould and Tanyell Cooke, “High Quality Child Care Is Out of Reach for Working Families,” Economic Policy Institute, October 6, 2015, http://www.epi.org/publication/child-care-affordability/.

15. Sandra Hofferth and Nancy Collins, “Child Care and Employment Turnover,” Population Research and Policy Review 19 (2000): 357–395.

16. Halley Potter, Lessons from New York City’s Universal Pre-K Expansion: How a Focus on Diversity Could Make It Even Better (New York: The Century Foundation, 2015), 3–4, http://www.tcf.org/bookstore/detail/lessons-from-new-york-citys-universal-pre-k-expansion.

17. For those whose employers offer them, some families also receive a tax-free “flexible spending” account for dependent care.

18. Stephanie Schmit and Rhiannon Reeves, Child Care Assistance in 2013 (Washington, D.C.: CLASP, March 2015), http://www.clasp.org/resources-and-publications/publication-1/Spending-and-Participation-Final.pdf.

19. “Quick Facts: Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC),” Tax Policy Center: A Joint Project of the Urban Institute and Brookings Institution (n.d.), http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/press/quickfacts_cdctc.cfm (accessed October 5, 2015).

20. Coauthor Julie Kashen serves as a senior policy adviser at Make It Work.