More than sixty-two years after the United States Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education,1 the nation is still wrestling with how to integrate our schools. Indeed, recent evidence indicates the problem has been worsening.2

School districts in some southern states that had made impressive progress under federal court oversight have seen their schools re-segregate as the courts have pulled back and even called into question the legality of voluntary desegregation plans. School districts in northern and western states never were substantially affected by Brown’s desegregation mandate because of the Supreme Court’s unwillingness to make Brown a truly national requirement. In fact, schools in northern and midwestern states such as New York, Illinois, Michigan, and New Jersey have consistently been the most severely segregated.3

Demographic changes in the nation and in many states have made the picture more complicated, but no less bleak. As the white and black student population percentages have declined, and the Hispanic and Asian percentages have increased, the concept of diversity and the meaning of school integration have shifted. Still, the reality on the ground is that the rapidly increasing Hispanic student population has joined black and white students in their educational isolation.

We desperately need to find a way to do better at meeting Brown’s clarion call and the demands of an increasingly diverse and interconnected world. The Morris School District in New Jersey (Morris district, or MSD) may offer such a path. Largely operating under the radar since its creation in 1971, the district has achieved impressive, if incomplete, success at attracting and maintaining a diverse student population and offering them the educational and social benefits of integrated education. Morris may provide an effective counter-narrative to the story told in most of the rest of the nation over the years since Brown.

The Morris district grew out of unlikely soil, which may make its story even more compelling. It resulted from a forced merger of two school districts in largely suburban Morris County. The merger was ordered by the state commissioner of education explicitly for racial balance reasons after the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that he had the power to take such action if he deemed it educationally appropriate and necessary to satisfy the state constitutional requirements for education.

To this point, the Morris district is the only one in New Jersey, indeed in the United States, to have been birthed in that manner. Its success at achieving and maintaining a remarkable degree of student diversity in a world where homogeneity is the norm makes one wonder why. By one benchmark of diversity—how a school district’s student population compares to statewide averages—the Morris district may be the most diverse school district in New Jersey. Its 2014–15 demographic profile is 52 percent white students, 11 percent black, 32 percent Hispanic, 5 percent Asian, and 35 percent receiving free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL, that is, low-income) against a state profile of 47 percent white, 16 percent black, 26 percent Hispanic, 9 percent Asian, and 38 percent FRPL.4

Beyond the districtwide numbers, the Morris district has achieved remarkable diversity at the school building level. Since the district has only one middle school and one high school, these are not where the diversity rubber meets the road. Rather, the test is the elementary school populations. There, the Morris district shines. Despite the fact that students live in relatively homogeneous, segregated neighborhoods, the elementary schools they attend defy that pattern. For example, to achieve perfect racial balance between black and white students at the elementary school level, only about 2.6 percent would have to change their school assignments.

The Morris district still struggles with two aspects of diversity, however. First,—in common with virtually every diverse school district in the country—it is still attempting to bring meaningful diversity to every program and course within its school buildings, from higher-level Honors and Advanced Placement courses to special education classifications and rosters of disciplinary actions. Second, in common with some but hardly all diverse districts across the country, the Morris district is trying to cope with the explosive growth of Hispanic students, many of them in recent years economically disadvantaged students from Central American countries where they often failed to receive a solid educational foundation in their own language and culture. Understandably, these students tend not to score well on standardized tests, especially in their early years in MSD. This contributes substantially to the Morris district’s record of relatively poor achievement levels in three substantially overlapping student categories—Hispanic, English Language Learners (ELL), and economically disadvantaged students—as compared to its relatively strong achievement levels for white and black students.

As to both challenges, the Morris district is manifesting a remarkably can-do spirit and a palpable will to succeed.

In all these respects, the study of the Morris district reported on here is designed ultimately to extract lessons for other school districts in New Jersey and the rest of the nation. This report begins by exploring briefly the historical, political, and legal context of educational integration in New Jersey, and how that led to the creation of the Morris School District. It then analyzes and discusses the successes—and the challenges—of MSD’s integration efforts. Along the way, it contrasts the successes of MSD with two other districts in New Jersey—Plainfield and New Brunswick—that attempted integration by district merger, but failed. It concludes by making recommendations not only for improvements in MSD’s approach, but for school districts across New Jersey and the country that are seeking to integrate their schools and classrooms.

The New Jersey Context and the Creation of the Morris School District

Prior to the Brown decision in 1954, New Jersey had a decidedly mixed history regarding school segregation and broader issues of equality. Unlike the southern states, it never had a formal and generally applicable state law requiring school segregation; nonetheless, the state actually had segregated schools into the 1950s. They resulted from formal policy or less formal action of local school districts. Ironically, though, in 1850, the state legislature adopted “permissive legislation,” on petition of Morris Township, to enable it to establish a separate school district for the exclusive use of “colored children,” and the result was the opening of the segregated Spring Street school in Morristown (at the time and until 1865, Morristown was part of Morris Township).5

New Jersey also had a bizarre episode in the late 1860s in connection with ratification of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. That amendment includes the equal protection clause, which was the basis of the Brown decision. To become effective, the amendment had to be ratified by three-fourths of the states. New Jersey and one other state initially ratified, but then rescinded their actions. Nonetheless, they were counted as ratifying and their support was necessary to achieve the requisite three-fourths. It was not until 2003 that New Jersey formally ratified the 14th Amendment (actually revoked its 1868 action to rescind its earlier ratification),6 the last state to do so.

To demonstrate that it was not “small-minded,” however, in 1881 New Jersey became one of the first states to enact a statute barring segregation in the schools,7 and the state courts strongly enforced that statute a number of times. In 1945, the legislature acted again to adopt the Law Against Discrimination.8 Two years later, in 1947, New Jersey became the only state to adopt an explicit constitutional amendment barring segregation in the schools.9

Still, at the time of the Brown decision in 1954, some New Jersey schools, especially in the southern part of the state, were formally segregated and many others were de facto segregated.

This dichotomy has continued to characterize New Jersey’s record regarding school segregation—strong laws on the books and feeble action on the ground.

This dichotomy has continued to characterize New Jersey’s record regarding school segregation—strong laws on the books and feeble action on the ground. Indeed, thanks to several landmark state court decisions in the 1960s and early 1970s, New Jersey is in the distinctive position of having the strongest state law in the nation barring school segregation and affirmatively requiring racial balance in the schools while it regularly is listed as having one of the country’s worst records of school segregation.

New Jersey’s state court decisions in the seventeen years following Brown—culminating in the 1971 state supreme court decision paving the way to the Morris School District merger, Jenkins v. Township of Morris School District10—are worthy of specific reference. They came during a period when federal court enforcement of Brown was best characterized by the oxymoronic phrase used by the U.S. Supreme Court in its 1955 follow-up decision to Brown—“all deliberate speed.” The enforcement was slow and limited, with the federal courts seeming to erect more obstacles to meaningful nationwide enforcement than to clear away obstacles imposed by the states.

The New Jersey courts, by contrast, acted boldly. Two decisions of the state supreme court were especially noteworthy. In 1965, the court ruled in Booker v. Board of Education of the City of Plainfield11 that there was no meaningful state constitutional distinction between de jure and de facto segregation, that both were equally harmful to black students and, therefore, equally offensive to the New Jersey constitution. The federal courts’ repeated unwillingness to adopt that view was perhaps the main limitation on Brown’s remedial scope.

In 1971, the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled in the Jenkins case that the state constitution required the achievement of racial balance in the schools “wherever feasible,” and that school district borders were not an impediment to that right of students and obligation of the state. As with the de jure-de facto distinction, the federal courts’ unwillingness to extend desegregation remedies across district lines, absent evidence of unconstitutional discrimination by all the school districts involved, sharply limited Brown’s reach and made it primarily a decision of regional rather than national scope.

The Jenkins case was brought to the New Jersey courts by eight residents of Morristown and Morris Township after they had unsuccessfully petitioned the state commissioner of education, both informally and formally, to take action to prevent the Morris Township school district from terminating its longstanding educational relationship with the Morristown school district. The petitioners’ claim was that the departure of the township’s predominantly white students from Morristown High School, likely coupled with the departure of other white students from Harding Township and perhaps from Morris Plains that also had sending relationships, would quickly lead to the high school becoming a predominantly black school, to the educational and social detriment of all.

The commissioner, Carl Marburger, expressed agreement with the petitioners’ position, but concluded he lacked the legal authority to provide the remedies sought—either requiring Morris Township to continue sending its high school students to Morristown, or ordering the creation of a regional district, preferably K–12. The New Jersey statutes did provide a voluntary mechanism for regionalization of districts, but it required approval by referendum of all the constituent districts, an unlikely occurrence here.

Not that the township was adamantly opposed to merger. In fact, opinion was closely divided on the subject. Remember that until 1865 Morris Township and Morristown had been a single municipality and school district, and for more than a century thereafter, township students attended Morristown High School, often without benefit of any formal legal agreement. As both the commissioner and the New Jersey Supreme Court recognized in their respective legal opinions in the Jenkins case, in many ways the two continued to function as a single municipality. Still, a modest majority of those who voted in an “advisory” referendum had preferred that the township build its own high school and thereby become its own K–12 district.

That prospect led to the litigation, to the landmark Jenkins decision, and to the merged Morris School District. It also led to opponents of merger predicting that the main result would be massive white flight from the merged district and a predominantly black Morristown High School. The failure of that prediction to materialize is at the heart of the study of the Morris district reported on here. If we can distill from the Morris district experience what enabled diversity to work there in a substantial if incomplete way, perhaps we can fashion a template that might enable other districts in New Jersey and in the rest of the country to achieve more diverse schools within their own boundaries.

Before this report proceeds to a deeper description and analysis of the Morris district, and to recommendations drawn from that effort, there are two more contextual points to address briefly. The first has to do with two other New Jersey school districts that were in the queue for a similar merger remedy, but whose turn never came. They were Plainfield and New Brunswick. Both, like Morristown, were relatively urban and diverse school districts whose high schools received predominantly white students from adjacent more suburban districts. They, like Morristown, were confronted with the departure of those white students, and sought to obtain remedial assistance from the commissioner of education to maintain their student diversity possibly by merger with their sending districts. Unlike Morristown, however, they failed to obtain that assistance.

Why the difference in result? Certainly, there were demographic and other distinctions at play, but there was a political dimension that may have been dispositive. Carl Marburger, the commissioner who ordered the Morris merger, failed by one vote in the state senate to be confirmed for another term as commissioner, and that failure was widely attributed to his merger order. Not surprisingly, successor commissioners became wary about acting as Marburger had.

Whatever the explanation, Plainfield and New Brunswick had to go it alone, and as a result, their current demographic profiles, as compared to Morristown’s, are startling. Whereas the Morris district has about 52 percent white students currently, Plainfield and New Brunswick each have less than 1 percent. They also have dramatically higher percentages of low-income students. It is unlikely we can establish a direct causal connection between the denial of merger and the degree of student segregation in those two districts, but the correlational evidence is powerful.

The second contextual point to be made about the Morris district is in the nature of a wall of honor. To the extent that the district is a success story, who are the primary authors? As with most success stories, there are many contenders. If it takes a village to raise a child, it must take at least a village to author a transformational success story such as this one.

While there are a number of worthy contenders, three people can be singled out as the main forces behind the success of the Morris district—Beatrice Jenkins, Carl Marburger, and Stephen Wiley, with the top billing going to Wiley, who passed away in October 2015 after a long life of distinguished service to New Jersey and to the Morris School District.

Beatrice Jenkins gave her name to the legal case and is otherwise worthy of recognition. She was a longtime black resident of Morristown, one of three Morristown residents who joined with five Morris Township residents to constitute the “Morris Eight,” the petitioners in the legal case that paved the way to the Morris School District. In collaboration with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. and the Urban League, these residents lent their names and efforts to the lawsuit.

Carl Marburger was certainly one of New Jersey’s most progressive and accomplished commissioners of education. He came to Trenton from Washington, D.C., where he had served on the education group of the Task Force on Poverty, the forerunner to the Office of Economic Opportunity, the federal antipoverty agency. Before that, he had been an assistant superintendent of the Detroit public schools. After Marburger’s premature departure from New Jersey, he became one of three cofounders of the National Committee for Citizens in Education, where he spent fifteen years advocating for the rights of parents. Notwithstanding his progressive bona fides, Marburger agonized over what to do in connection with the Morris district. As it has on so many controversial education issues over the years, the New Jersey Supreme Court got him off the fence by its decision in the Jenkins case.

Finally, there was Steve Wiley. Wiley was born, raised, and public-school-educated in Morristown and Morris Township. He came by his lifelong commitment to the Morris district schools the old-fashioned way—his father, Burton, was a longtime superintendent of the district. Wiley graduated from Morristown High School in 1947. He went on to Princeton and Columbia Law School, became a successful lawyer, businessman, politician and public benefactor. He also was a nature lover, a woodworker, a gardener and a poet. As lawyer for the Morristown school board, he was instrumental in the Jenkins case, and he founded the Morris Educational Foundation. A comment about Steve Wiley in an article celebrating his life captures the essence:

Anyone who wants to appreciate the late Steve Wiley’s impact on Greater Morristown should attend Saturday’s homecoming game at his alma mater, Morristown High School. . . . Today, we live and work and go to school in one of the only truly diverse communities in New Jersey. . . . Look at the football team, the cheerleaders, the band, the kids in the stands, the supervisors and coaches on the field and you will see something really beautiful and I think unique. We all play together and celebrate together and solve our problems together. We like each other. Steve Wiley did that. And I am so grateful.12

An equally fitting statement comes from Wiley himself:

Our schools teach the ABC’s with distinction, but young people in Morristown High and the grade schools also learn the D’s, E’s and F’s. By association and experience they learn about democracy and diversity, about equal opportunity and ethnic strengths, about freedom and fraternity, about the whole alphabet of America.13

A Case Study of the Morris School District as a Remedial Model

To move beyond the unique history and status of the Morris School District (MSD) to its potential to be a remedial model for New Jersey and the rest of the United States requires a deeper understanding of the district. This section of the report describes MSD from a quantitative perspective sketching out a demographic profile of its constituent communities and its student population, the degree to which its individual schools mirror the diversity of the district at large, and the educational outcomes of its students, both overall and by relevant subgroups.

A Demographic Profile of the Morris School District Municipalities

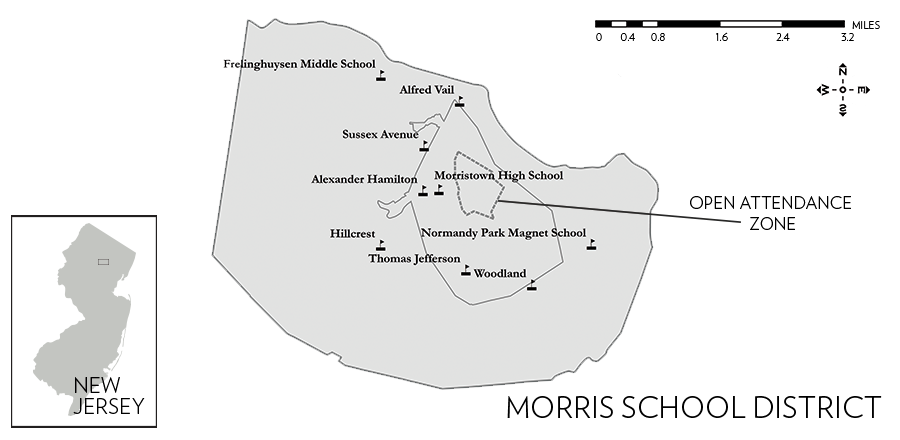

The Morris School District is located in Morris County, New Jersey, and includes, as a formal matter, Morris Township and Morristown. Although adjoining Morris Plains sends its high school students to Morristown High School in MSD, it maintains its own schools for kindergarten through eighth grade. The educational relationship between Morris Plains and the Morris district is a close and longstanding one, though, so Morris Plains and its students will be included in the demographic profiles of the MSD’s municipalities and schools. Henceforth, for ease of reference, Morris Plains will be treated as one of the MSD’s constituent municipalities.

As shown in Figure 1, the Morris School District’s location in northern New Jersey is approximately thirty miles east of New York City. Much of the district is comprised of detached suburban housing, although there are more dense areas at the core of the district in Morristown. The most dense areas of the district are located in the open attendance zone at the heart of Morristown, which is a centerpiece of the district’s successful effort to diversify its elementary schools (see discussion of the student assignment policy in the Analysis and Discussion section; see Appendix B for a discussion of the quantitative methods).

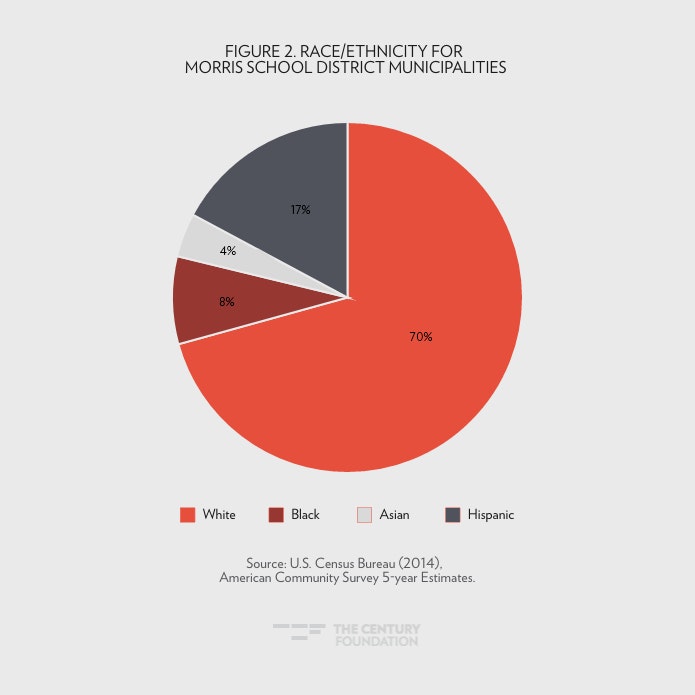

The total population of the municipalities that we include in the Morris School District is 46,764—22,549 people live in Morris Township, 18,580 people live in Morristown, and 5,635 people live in Morris Plains. As shown in Figure 2, 70 percent of the total population of the three municipalities is white, 17 percent is Hispanic, 8 percent is black, and 4 percent is Asian. The median household income for the three municipalities is $98,424 per year—the median household income is $127,074 in Morris Township, $110,167 in Morris Plains, and $75,696 in Morristown. The child poverty rate is extremely low in both Morris Plains (1.3 percent) and Morris Township (3.9 percent); however, the child poverty rate in Morristown is a much higher 20.9 percent. As Figure 3 shows, 92 percent of the population over the age of twenty-five in the three municipalities has a high school diploma or a GED and 57 percent of the population has at least a bachelor’s degree. However, only 46.3 percent of the population in Morristown holds a bachelor’s degree or more.14

The interactive map shows the distribution of the population in the Morris School District municipalities by race and ethnicity. As it illustrates, there is a lower concentration of white people in Morristown than in the other two municipalities, few white residents live in the open attendance zone, and several census blocks throughout the Morris School District are exclusively white. It also shows that an overwhelming majority of the Hispanic population in the MSD municipalities lives in Morristown, and there is a particularly high concentration of Hispanic people in the open attendance zone. The map indicates that the black population is more dispersed, but that there is a high concentration of black people living in Morristown and in the open attendance zone. Finally, it illustrates that the Asian population is also dispersed throughout the MSD municipalities, but there is a very low concentration of Asian people in the open attendance zone.

Figure 4. Proportion of Population by RACE/ETHNICITY

NOTE: DASHED LINE INDICATES OPEN ATTENDANCE ZONE. SOLiD LINE INDICATES MUNICIPAL BOUNDARIES.

Given the correlation between home ownership and both social and economic stability, Figure 5 provides some useful insight into neighborhood variation across the school district. As seen in Figure 5, a large proportion of the population in Morris Township and Morris Plains owns the homes where they live. By contrast, a large proportion of the population in Morristown, particularly in the open attendance zone, rents their residences.

FIGURE 5. PROPORTION OF HOUSEHOLDS THAT RENT

NOTE: DASHED LINE INDICATES OPEN ATTENDANCE ZONE. SOLiD LINE INDICATES MUNICIPAL BOUNDARIES.

Overall, the Morris School District is composed of three municipalities with notably different demographic profiles. Morris Township has a population that is largely white, highly educated, and economically stable. Morris Plains has a similar profile, though the median household income and educational attainment levels are a bit lower. On the other hand, Morristown is a majority-minority municipality with a median household income that is more than $50,000 lower than that of Morris Township, a child poverty rate over 20 percent, and a comparatively low level of educational attainment.

Population Change: 1970–2010

Between 1970 and 2010, the population of the MSD municipalities increased by 8.6 percent. While the overall population increased, there was a dramatic decrease in the white and black population during this period (see Figure 6 and Table 1). Conversely, there was a dramatic increase in the Hispanic15 and Asian populations.

| Table 1. Percent Change in Morris School District Municipalities’ Population, 1970-2010 | |||||

| 1970-1980 | 1980-1990 | 1990-2000 | 2000-2010 | 1970-2010 | |

| Total Population | -5.2% | 2.4% | 10.2% | 1.5% | 8.6% |

| White | -10.8% | -2.6% | 1.2% | -5.2% | -16.6% |

| Black | 4.8% | -4.4% | -12.3% | -10.7% | -21.6% |

| Asian | 80.9% | 54.5% | 24.9% | 248.9%* | |

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish | 281.4% | 137.6% | 120.1% | 37.8% | 2648.8% |

| *This accounts for the population change from 1980-2010.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Decennial Census. |

|||||

The largest percent decrease in the white population took place between 1970 and 1980. This coincides with the period when MSD desegregated its schools in accordance with the 1971 merger order by the state commissioner of education. While the white population decreased by 10.8 percent between 1970 and 1980, the black population increased by 4.8 percent and the Hispanic population increased by 281.4 percent during this ten-year period. The degree to which the decrease in the white population is connected to the merger order is unclear. Between 1970 and 1980, the white population of New Jersey as a whole decreased at a comparable rate (8.4 percent). One may hypothesize that the decrease in the white population of the Morris School District is related to a statewide trend; however, unlike in the state as a whole and the Morris School District, the white population of Morris County as a whole increased by 1.4 percent. Given that the change in the white population of the Morris School District differed greatly from the overall trend of the white population in the county, it is possible that a portion of this population shift occurred in response to the merger order. While a quantitative analysis fails to either confirm or deny a causal link between the merger order and changes in population, qualitative data from Morristown residents who lived through the merger indicate that there was a degree of white flight in response to the merger.

Demographic Profile of the Schools in the Morris School District

The Morris School District has an operating budget of approximately $112,000,000 and employs 427 teachers, 107 other certificated staff, and 371 non-certificated staff.16 This equates to per-pupil spending of $21,089, which outpaces the average per-pupil spending across New Jersey. The teaching staff is overwhelmingly white (85.5 percent) and female (76.6 percent). 4.9 percent of teachers are black, 7.0 percent are Hispanic, and 2.6 percent are Asian.17

The district serves 5,226 students from pre-kindergarten through twelfth grade. Morristown High School serves 1,672 students and the district’s single middle school serves 1,144 students in grades six through eight. Normandy Park, a district magnet school, serves 368 students in kindergarten through fifth grade. Finally, there are three pairs of kindergarten through second grade and third through fifth grade sister schools that serve students from kindergarten through fifth grade. Table 2 provides a summary of student enrollment by demographic group for all MSD schools, and Figure 7 shows the locations of schools across the district.

| Table 2. Morris School District Enrollment (2014-2015) | |||||||

| Hillcrest/Alexander Hamilton | Woodland/ Thomas Jefferson | Alfred Vale/Sussex | Normandy Park | Frelinghuysen Middle School | Morristown High School | District Total | |

| Number of Students | 589 | 622 | 655 | 368 | 1144 | 1672 | 5226 |

| % Male | 50.3% | 49.7% | 51.0% | 48.6% | 52.1% | 51.9% | 51.1% |

| % Female | 49.7% | 50.3% | 49.0% | 51.4% | 47.9% | 48.1% | 48.9% |

| % White | 51.4% | 50.8% | 53.6% | 45.1% | 51.7% | 56.8% | 52.3% |

| % Black | 10.2% | 9.0% | 10.4% | 10.1% | 11.9% | 11.4% | 10.9% |

| % Hispanic | 35.3% | 34.2% | 31.5% | 39.4% | 30.4% | 27.0% | 31.8% |

| % Asian | 2.7% | 5.9% | 4.0% | 5.4% | 5.6% | 4.3% | 4.6% |

| % Free Lunch | 34.8% | 31.4% | 31.6% | 34.2% | 28.0% | 20.9% | 29.0% |

| % Reduced-Price Lunch | 5.1% | 5.8% | 5.5% | 3.0% | 6.6% | 6.0% | 5.8% |

| % Free/Reduced Price Lunch | 39.9% | 37.1% | 37.1% | 37.2% | 34.6% | 26.9% | 34.8% |

| % Not Qualified for Free/Reduced Price Lunch | 60.1% | 62.9% | 62.9% | 62.8% | 65.4% | 73.1% | 65.2% |

| % Limited English Proficiency | 13.6% | 13.0% | 7.8% | 21.5% | 4.0% | 8.2% | 9.1% |

| % Not Limited English Proficient | 86.4% | 87.0% | 92.2% | 78.5% | 96.0% | 91.8% | 90.9% |

| Source: New Jersey Department of Education (2015), 2014-2015 School Enrollment File. | |||||||

A majority of students in the Morris School District identify as white. As Figure 8 shows, 32 percent of students identify as Hispanic, 11 percent as black, and 5 percent as Asian. As Figure 9 shows, 35 percent of students qualify for free- or reduced-price lunch and 9 percent of students are classified as limited English proficient. While the distribution of student subgroups across the four schools serving students from kindergarten through fifth grade is comparable, it is worth noting that the magnet school is the sole majority-minority environment and that there is a larger concentration of ELL students at this school (21.5 percent) than at the three K–5 sister schools (7.8 percent to 13.6 percent).

Similar to other areas throughout New Jersey, a portion of children in the Morris School District attends private schools. While the proportion of children in the Morris School District who opt out of the public school system is close to the state average at both the elementary and secondary levels, the proportion of students who attend private school is not evenly distributed across the three municipalities that make up the district. As shown in Table 3, 3.2 percent of elementary school students in Morristown attend private schools, while a much larger 17.5 percent of children in Morris Township opt out of the public school system. A similar trend exists at the secondary level, where 7.5 percent of children in Morristown and 22.1 percent of children in Morris Township go to private schools. The proportion of children in Morris Township who go to private schools is nearly twice the average for New Jersey as a whole and much higher than the rates in Plainfield and New Brunswick. Given that Morris Township has a much higher median income than Plainfield and New Brunswick, the fact that its private school attendance rate is comparatively high is, perhaps, unsurprising.

| Table 3. Distribution of Students Who Attend Private and Public Schools | ||||

| Kindergarten through Grade 8 | Grade 9 through Grade 12 | |||

| % Public | % Private | % Public | % Private | |

| Morristown | 96.8% | 3.2% | 92.5% | 7.5% |

| Morris Township | 82.5% | 17.5% | 77.9% | 22.1% |

| Morris Plains | 95.1% | 4.9% | 92.6% | 7.4% |

| Morris School District* | 87.9% | 12.1% | 85.6% | 14.4% |

| New Jersey | 89.4% | 10.6% | 88.6% | 11.4% |

| Plainfield | 92.3% | 7.7% | 89.5% | 10.5% |

| New Brunswick | 96.5% | 3.5% | 95.1% | 4.9% |

| * This includes Morristown and Morris Township for K through 8 schools and all three municipalities for Grades 9-12.

Source: 2014 American Community Survey. |

||||

Measures of School and Neighborhood Segregation

The three pairs of kindergarten through second grade and third through fifth grade sister schools and one magnet school serving children in kindergarten through fifth grade are effectively integrated by race and economic advantage/disadvantage. As illustrated by Table 4, which provides a range of segregation measures (including dissimilarity, isolation, and exposure indices), there are extremely low levels of racial and economic dissimilarity among MSD schools serving children in kindergarten through grade five. However, Table 4 also highlights the fact that there is persistent residential segregation among municipalities and neighborhoods delineated by census tracts. For example, while only 2.6 percent of black or white students would need to move schools to create perfectly proportional populations of black and white students at the K–5 schools in the Morris School District, 42.1 percent of black or white residents would need to move neighborhoods (as delineated by census tracts) in order to create perfectly proportional populations of black and white people across neighborhoods.

Dissimilarity indices between white and black students, white and Hispanic students, black and Hispanic students, and students who qualify for free- or reduced-price lunch and students who do not are all less than 5.0. In other words, less than 5 percent of these populations would need to move schools to create student populations that are perfectly proportional by these demographic groups. Isolation indices and exposure indices produce similar results indicating that black, white, Hispanic, economically disadvantaged, and non-economically disadvantaged students attend schools where they are exposed to students from each demographic group in a manner that is proportional to the total population for the school district.

Dissimilarity indices between Asian students and each of the other racial/ethnic groups are slightly elevated (11.2 to 15.5). Similarly, the dissimilarity index for students classified as limited English proficient and students who are not is slightly elevated at 13.6. This means that Asian students and students classified as limited English proficient are not proportionally distributed across schools, and, therefore, are more isolated.

| Table 4a. Measures of Segregation for White Students and Population | |||||

| K-5 Schools | K-8 Towns | K-8 Census Tracts | 9-12 Towns | 9-12 Census Tracts | |

| Dissimilarity with blacks | 2.6 | 33.7 | 42.1 | 35.1 | 43.8 |

| Dissimilarity with Hispanics | 4.4 | 48.4 | 51.0 | 47.8 | 49.6 |

| Dissimilarity with Asians | 15.2 | 10.3 | 14.1 | 10.3 | 13.6 |

| The average white is in a space with | |||||

| a % white of | 51.2% | 72.7% | 76.3% | 74.2% | 77.3% |

| a % black of | 9.9% | 7.8% | 6.7% | 7.1 | 6.2 |

| a % Hispanic of | 34.5 | 15.0 | 12.2 | 14.2 | 11.7 |

| a % Asian of | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 4.7 |

| Percent White | 51.0 | 68.5 | 68.5 | 70.4 | 70.4 |

| Sources: NJ DOE Enrollment File 2014-2015 and 2014 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. | |||||

| Table 4b. Measures of Segregation for Asian Students and Population | |||||

| K-5 School | K-8 Towns | K-8 Census Tracts | 9-12 Towns | 9-12 Census Tracts | |

| Dissimilarity with whites | 15.2 | 10.3 | 14.1 | 10.3 | 13.6 |

| Dissimilarity with blacks | 15.5 | 23.4 | 40.6 | 24.8 | 40.1 |

| Dissimilarity with Hispanics | 11.2 | 38.1 | 47.9 | 37.5 | 45.2 |

| The average Asian is in a space with | |||||

| a % white of | 50.6 | 69.2 | 74.0 | 70.8 | 74.9 |

| a % black of | 9.8 | 8.6 | 7.3 | 8.0 | 6.9 |

| a % Hispanic of | 34.8 | 17.7 | 13.2 | 16.8 | 12.8 |

| a % Asian of | 4.8 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 4.4 | 5.4 |

| Percent Asian | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.4 |

| Sources: NJ DOE Enrollment File 2014-2015 and 2014 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. | |||||

| Table 4c. Measures of Segregation for Black Students and Population | |||||

| K-5 School | K-8 Towns | K-8 Census Tracts | 9-12 Towns | 9-12 Census Tracts | |

| Dissimilarity with whites | 2.6 | 33.7 | 42.1 | 35.1 | 43.8 |

| Dissimilarity with Hispanics | 4.3 | 14.7 | 20.8 | 14.3 | 20.1 |

| Dissimilarity with Asians | 15.5 | 23.4 | 40.6 | 24.8 | 40.1 |

| The average black is in a space with | |||||

| a % white of | 51.0 | 61.3 | 52.7 | 62.4 | 54.3 |

| a % black of | 10.0 | 10.3 | 13.6 | 10.0 | 13.1 |

| a % Hispanic of | 34.6 | 23.4 | 29.8 | 23.2 | 28.8 |

| a % Asian of | 4.4 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 3.8 |

| Percent black | 10.0 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 8.0 | 8.0 |

| Sources: NJ DOE Enrollment File 2014-2015 and 2014 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. | |||||

| Table 4d. Measures of Segregation for Hispanic Students and Population | |||||

| K-5 School | K-8 Towns | K-8 Census Tracts | 9-12 Towns | 9-12 Census Tracts | |

| Dissimilarity with whites | 4.4 | 48.5 | 51.0 | 47.8 | 49.6 |

| Dissimilarity with blacks | 4.3 | 14.7 | 20.8 | 14.3 | 20.1 |

| Dissimilarity with Asians | 11.2 | 38.1 | 47.9 | 37.5 | 45.2 |

| The average Hispanic is in a space with | |||||

| a % white of | 50.8 | 56.3 | 45.6 | 58.1 | 48.1 |

| a % black of | 9.9 | 11.4 | 14.2 | 10.9 | 13.5 |

| a % Hispanic of | 34.8 | 27.9 | 36.9 | 26.7 | 35.1 |

| a % Asian of | 4.5 | 4.4 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 3.3 |

| Percent Hispanic | 35.0 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 17.2 | 17.2 |

| Sources: NJ DOE Enrollment File 2014-2015 and 2014 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. | |||||

| Table 4e. Measures of Segregation for Limited Language Profiency Students | |||||

| K-5 School | K-8 Towns | K-8 Census Tracts | 9-12 Towns | 9-12 Census Tracts | |

| Dissimilarity with no LEP | 13.6 | ||||

| The average LEP child is in a space with | |||||

| a % LEP of | 14.6 | ||||

| a % no LEP of | 85.5 | ||||

| Percent LEP | 13.0 | ||||

| Sources: NJ DOE Enrollment File 2014-2015 and 2014 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. | |||||

| Table 4f. Measures of Segregation for Free/Reduced Price Lunch Students | |||||

| K-12 School | K-8 Towns | K-8 Census Tracts | 9-12 Towns | 9-12 Census Tracts | |

| Dissimilarity with no FRL | 2.3 | ||||

| The average FRL child is in a space with | |||||

| a % FRL of | 37.9 | ||||

| a % no FRL of | 62.1 | ||||

| Percent FLR | 37.9 | ||||

| Sources: NJ DOE Enrollment File 2014-2015 and 2014 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. | |||||

| Table 4g. Measures of Segregation for Child Poverty in Students and Population | |||||

| K-12 School | K-8 Towns | K-8 Census Tracts | 9-12 Towns | 9-12 Census Tracts | |

| Dissimilarity with non-child poverty | 43.0 | 52.7 | 46.4 | 54.7 | |

| The average child in poverty is in a space with | |||||

| a % child poverty of | 17.0 | 27.6 | 16.7 | 27.1 | |

| a % non-child poverty of | 83.0 | 72.4 | 83.3 | 72.9 | |

| Percent Children in Poverty | 21.0 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 21.0 | |

| Sources: NJ DOE Enrollment File 2014-2015 and 2014 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. | |||||

Educational Outcomes in the Morris School District

Educational outcomes in the Morris School District are mixed. Table 5 shows mean scale scores and the percent of students who score at a level deemed proficient on the 2014 English Language Arts (ELA) and Math New Jersey Assessment of Skills (NJASK) for students in the third, fifth, and eighth grades. It also shows mean scale scores and percent proficient on the 2014 ELA and Math High School Proficiency Assessment (HSPA).

When compared to students across New Jersey, students in the Morris School District score close to average at all grade levels on both the ELA and math exams. When compared to students at schools with similar socioeconomic profiles,18 students in the Morris School District score below average at virtually all grade levels on both the ELA and math exams (the one exception is fifth grade ELA scores).

When compared to students at schools in the highly segregated school districts of New Brunswick and Plainfield, students in the Morris School District on average do much better on ELA and math exams at all grade levels. However, it is necessary to note that Plainfield is designated as part of the state’s District Factor Grouping (DFG) B, and New Brunswick as part of DFG A; both of these DFGs are characterized by low socioeconomic status. Because of the strong correlation between socioeconomic status and student achievement on standardized tests, it is difficult to infer much about the impact school desegregation has on student outcomes from these data.

| Table 5. Percent Proficient and Mean Scale Scores on 2014 NJASK and HSPA ELA and Math Exams | ||||||||||||||||

| Third Grade | Fifth Grade | Eighth Grade | Tenth Grade | |||||||||||||

| ELA | MATH | ELA | Math | ELA | Math | ELA | Math | |||||||||

| % Proficient | Mean Scale Score | % Proficient | Mean Scale Score | % Proficient | Mean Scale Score | % Proficient | Mean Scale Score | % Proficient | Mean Scale Score | % Proficient | Mean Scale Score | % Proficient | Mean Scale Score | % Proficient | Mean Scale Score | |

| Morris School District | 66.0 | 206.6 | 73.8 | 230.3 | 75.3 | 215.7 | 86.3 | 244.7 | 78.2 | 218.7 | 75.2 | 226.4 | 92.6 | 238.3 | 78.2 | 229.4 |

| DFG GH | 77.4 | 212.9 | 84.7 | 243.0 | 75.2 | 214.1 | 88.1 | 244.6 | 87.8 | 227.0 | 80.8 | 236.6 | 96.6 | 242.2 | 86.7 | 233.2 |

| New Jersey | 65.5 | 205.8 | 75.5 | 230.6 | 62.3 | 205.6 | 79.8 | 233.8 | 79.8 | 220.1 | 71.5 | 225.2 | 93.2 | 236.8 | 78.9 | 226.1 |

| Plainfield School District | 38.8 | 190.5 | 52.7 | 203.9 | 32.0 | 187.5 | 59.6 | 208.8 | 52.2 | 199.8 | 23.9 | 183.8 | 80.2 | 216.3 | 46.2 | 199.0 |

| New Brunswick School District | 24.1 | 183.5 | 49.5 | 199.6 | 25.9 | 184.1 | 63.9 | 211.2 | 48.4 | 198.3 | 45.1 | 191.7 | 82.4 | 221.1 | 53.6 | 204.0 |

| Source: NJ DOE Statewide Assessment Reports | ||||||||||||||||

While overall student achievement in the Morris School District is average in comparison to the rest of New Jersey, student subgroup data reveal a number of noteworthy trends. Table 6 shows the percent of Morris School District students scoring as well as or better than other students across the state of New Jersey by demographic subgroup, grade, and subject. This analysis uses mean scale scores from the 2010–2014 NJASK and HSPA tests and the number of valid test scores for each demographic subgroup to determine the average percent of MSD students scoring as well as or better than other students across the state of New Jersey by demographic subgroup.

On average, white students in the Morris School District outperform the white students in New Jersey on all tests and at all grade levels. In the fifth grade, the average white student in the Morris School District does as well as or better than 90.6 percent of their white peers in all public schools across the state on the ELA exam and as well as or better than 90.8 percent of their white peers across the state on the math exam. Similarly, black students in the Morris School District on average outperform their black peers at all public schools across the state on both third grade exams, both fifth grade exams, both eighth grade exams, and the tenth grade ELA exam. Conversely, with few exceptions, Hispanic students, economically disadvantaged students, and students classified as limited English proficient underperform when compared to their peers from the same subgroups across the state. English Language Learners in the Morris School District only do as well as or better than 23.6 percent of other ELL students in New Jersey on the tenth grade ELA exam. These data suggest that the Morris School District does a good job of serving white and black students, but that it fails to adequately meet the needs of Hispanic, economically disadvantaged, and ELL students.19

Finally, graduation rates in the Morris School District are average for New Jersey. The mean four-year adjusted cohort graduation rate from 2011-2015 in the Morris School District was 89.44 percent as compared to the state average of 89.77 percent. This ranks the Morris School District’s high school graduation rate as 185th of the 296 districts serving high school students across the state.20

While the analysis provided in this section does offer some insight into educational outcomes in the Morris School District, it is important to note that much of it is based on the results of standardized tests that are administered at a single moment in the school year, and that only evaluate certain prescribed skills and knowledge in math and ELA. Such limited measures must not be given more credence than they deserve. Therefore, it is essential to consider this quantitative analysis within the context of the qualitative data presented throughout the rest of this report.

| Table 6. Percent of Morris School District Students Scoring as Well as or Better than Other Students Across the State of New Jersey (five-year averages) | ||||||||

| Third Grade | Fifth Grade | Eighth Grade | Tenth Grade | |||||

| ELA | Math | ELA | Math | ELA | Math | ELA | Math | |

| All Students | 50.2 | 47.7 | 69.4 | 66.1 | 58.4 | 61.5 | 51.4 | 57.9 |

| White | 71.9 | 73.0 | 90.6 | 90.8 | 80.0 | 86.0 | 78.9 | 81.5 |

| Black | 63.3 | 58.2 | 81.2 | 76.2 | 66.8 | 68.0 | 52.2 | 48.6 |

| Hispanic | 28.5 | 22.2 | 59.3 | 51.7 | 51.4 | 57.9 | 34.9 | 46.6 |

| Asian | 50.7 | 46.0 | 61.3 | 64.2 | 46.3 | 37.8 | 36.3 | 42.4 |

| Economically disadvantaged | 27.3 | 17.9 | 60.6 | 45.9 | 42.8 | 44.6 | 34.7 | 32.1 |

| Non-economically disadvantaged | 59.0 | 58.4 | 81.3 | 82.3 | 63.7 | 67.5 | 54.5 | 60.9 |

| English language learners | 17.9 | 17.8 | 46.2 | 40.5 | 66.8 | 68.2 | 23.6 | 14.9 |

| Source: 2010-2014 NJASK and HSPA, NJ DOE. | ||||||||

Analysis and Discussion of the Successes and Failures of the MSD Effort

The Morris School District’s long-term interest and investment in making diversity work, both academically and socially, have contributed to its success. In fact, for forty-five years, Morris has been able to both attract and maintain a racially, ethnically and socioeconomically diverse student body, desegregated schools, and a strong academic reputation (that goes beyond test score averages). This has occurred even as the demographics have shifted from a black/white population in the 1970s to a black/white/Hispanic population in 2016. A key motivating factor behind generating this report was to understand why and how the MSD has succeeded where so many others have failed.

Our emerging qualitative findings on the Morris School District in this section are derived from sixty-four individual interviews and eight focus groups with a diverse sample of Morristown respondents at the community, district, and school level (see Appendix C for a description of data collection and methods). The semi-structured interviews with district administrators, teachers, school board members, parents, and students were triangulated with school and classroom observations. During this exploration, we found that there were three main reasons behind the Morris School District’s success: (1) the Morristown community is morally committed to public education and the collective benefits of diversity; (2) community members believe that, in order to have a successful district, you need to have a supportive community and strong family partnerships with the schools; and (3) although, the district’s response to some of the challenges that school diversity imposes on the schools has been slow and uneven over the years, respondents believe that the positives outweigh the negatives.

While the merger and associated policies created districtwide diversity and desegregated schools at the building level, students in diverse schools—in MSD as well as in other diverse districts—are often educated in classrooms that are less diverse, whether the measure is race, ethnicity, language or socioeconomic status (SES). MSD is aware of the problem and has made efforts to progress toward true integration, including changing the admissions process for gifted and talented classes (G&T), creating heterogeneous math groups in elementary school, eliminating the lowest B-level track in high school, using multiple measures for course placement decisions in middle school, and hiring a high school counselor to support students of color and make sure they are on track for college. Yet, in many respondents’ eyes, there remains much work to be done to achieve true integration inside school walls. In the sections that follow, we outline the successes and challenges of MSD—a district that chooses to make diversity work.

Moral Commitment to Public Education and Collective Benefits of Diversity

Part of the Morris district’s success is traceable to the investment in making diversity work in the schools that took root in the community at the time of the school merger or even earlier, and continues to this day. Respondents who experienced the merger first hand spoke about the “fertile ground” in which the merger took place, both in terms of the people and the place. At the time of the merger, an influential group of residents came together to support public education and spearhead the effort to regionalize the separate K–8 Morris Township school district with Morristown’s K–12 district. This pro-merger group of residents feared that, if the mostly white township pulled its students out of Morristown High School, the school would eventually become an all-black school. They worried that, if the township built a separate high school and stopped sending its students to Morristown, there would be rampant white flight. Steve Wiley, who was the leader of the pro-merger movement, was quoted in a recent newspaper article about the reason he pushed for the regional school district: “Separate, segregated high schools would hasten white flight from Morristown, dooming it to the same turmoil afflicting New Jersey’s urban centers.”21

Another influential person who worked with Wiley in the fight to regionalize the two districts was a black township resident named Wanda.22 In her interview, she said that it took “people of good will” in Morristown to fight for equal opportunity in housing and education. Like other school desegregation battles fought across the country, the integration movement in Morris started with a strong group of supporters. In Morristown, this group included fair housing advocates, the NAACP, the Urban League, school board members, educators and the clergy.

An important part of making diversity work in the community, therefore, was the enforcement of the state’s fair housing law, which we were told was an essential first step toward school integration. For instance, Wanda, whose family was the first black family to move into the majority white township in 1955, believed that, in order to have racial balance in the schools, you had to have fair housing laws to achieve racial balance in housing “because of the theory of the neighborhood school.”

“If there’s ever going to be a place where true integration is going to happen, it’s going to be in Morris County.”

Of course, there also were people, mostly in the township, who preferred the status quo of segregated neighborhood schools, and voted against the merger. Yet, according to Wanda, there were enough people in the town and township “willing to bring about social change” who were not afraid of “going to school with the black people.” As an example of how special the Morristown community is, she said, that the “Morris School District was the first to honor Dr. King’s birthday as a national holiday. These types of things wouldn’t happen in just any district. It may be that you had enough blacks, enough minorities, enough to make the difference, you know? You had enough white people of good will to bring it about.” Wanda declared, “If there’s ever going to be a place where true integration is going to happen, it’s going to be in Morris County.”

In our interviews, respondents consistently cited community activism around fair housing and school integration for making Morristown a successful place in which to live for decades after the merger occurred. In fact, Jessica, who is the director of a prominent community organization in town, explained that this group of pro-merger residents who were around for a long time would get their contemporaries to say, “I’m going to live in Morristown and send my kids to that high school and I’m going to elect people I know to the school board and it’s going to stay a great high school for everybody.”

We found that current homeowners and parents want the school district to succeed, even if they choose private school for their children’s education, because, as one white parent remarked, “a strong school system is the foundation of a strong community.” This symbiotic relationship between the community and schools was evident when respondents described Morristown. As one principal, Cindy, remarked, the community has “a core group of people who really believe in public education, supporting public education.” The town is also known for being a downtown destination. Cindy said: “everybody shops here. People go down to the Green [the town square]. They go to the local restaurants. It’s a very vital community, so I think people—they walk around together. People aren’t isolated in their own little neighborhoods, which is nice.” This environment, where the school district is seen as the bedrock of the community, continues to be part of the attraction of living in Morristown today.

Achieving School-Level Diversity Post-Merger

The district’s commitment to making diversity work is evident by its student assignment plan that extends beyond the district level to the school level. After the merger, respondents explained that the district decided to implement the “Princeton Plan” to diversify elementary schools by pairing a primary (K–2) school with an intermediate (3–5) school—with one located in the town and the other paired school located in the township. The creators of the plan also moved teachers around in order to mix them up between former Morristown and Morris Township schools.

The Princeton Plan had been developed in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1948. Under it, schools were grouped by grade level, rather than geography, as a way to achieve diversity. Today, many districts adopt the Princeton Plan for economic purposes rather than for diversity. MSD also uses geography to achieve racial diversity in schools by designating the center of town as an open assignment area because it was, and still is, where many low-income black and Hispanic residents live. Students living in this area are bused to various neighborhood schools across the district to achieve racial balance and desegregate schools. Every other assignment area has a neighborhood school.

When you compare other “diverse” districts in New Jersey, such as Montclair or South Orange-Maplewood, with Morris, the other districts typically have a higher level of between-school segregation caused by neighborhood residential segregation. In Morris, as one white parent said, “it is an effort here [to desegregate elementary schools], but it’s not an effort on the part of the citizen. That’s taken care of by the school district, so it’s not at the burden of me and everyone realizes that whichever elementary your child goes to, there’s a balance.” In other words, the “burden” to choose school diversity is not on individual parents since the district does the work for them with the Princeton Plan and the open assignment area. Even with the presence of relatively segregated neighborhoods in Morris and demographic change, the schools remain diverse because the structures are in place to accommodate those changes. The other benefit of diverse elementary schools is that students are exposed to diversity beginning in kindergarten. This makes for a smoother transition to middle school and high school because the students have been educated in diverse classrooms throughout their K–5 educational careers.

Choosing School Diversity and Well-Balanced Curriculum and Extracurricular Activities

Parents have school choice options in Morris County, including the surrounding white homogeneous suburban districts and private schools. As noted, the proportion of children in Morris Township who go to private schools is nearly twice the average for New Jersey as a whole. Therefore, those families with means to choose, who enroll their children in the MSD public schools do so in part because they value diversity for their children’s educational experience. White parents, in particular, said that they look beyond the lower test score averages and rankings in Morristown because they know the district has much to offer—namely diversity and high quality academics and extracurricular activities.23 As one white public school parent in our study commented, “Nobody lives here by accident; we all made a conscious decision to choose diversity.”

“Nobody lives here by accident; we all made a conscious decision to choose diversity.”

A white district administrator whom we interviewed, named Helen, said she works with realtors and talks to families who are considering moving to Morristown—often parents or couples without children moving from New York City. She explained: “People have the opposite perception of what a good community is. [Instead of wanting a racially homogeneous district,] a diverse community is becoming something that people are intentionally seeking rather than avoiding.” Helen believes that people are more “enlightened” today and “recognize how important diversity is for a strong community”:

People are slowly recognizing that this is a good thing, that a community is healthier and richer just like a garden is healthier and richer if you have different things there. I think in Morris County, probably more so than maybe upper Bergen County where most of this community is affluent and purely white, Morristown is—we’re different. We’re different, so if someone says “I want to move to Morris County” and they’re looking at SAT scores, average SAT scores, or “I want to walk past a school and see only kids that look like my kids”—it’s difficult.

As one realtor told us, more and more parents are realizing that the “test scores [in MSD] are not the highest,” as compared to “lily white places like Chatham, Madison, or Millburn” because of the diversity. They also realize that test scores are not the only indicator of educational success. There are nonacademic outcomes that parents are also looking for. For instance, during the interview with Peter, a white father who relocated to New Jersey for his job about ten years ago, he explained how he and his wife weighed the pros and cons of the Morris district when choosing where to live and send their children to school:

I mean, if you think about the other places we were looking [at] before we bought our house—Randolph, Madison, Summit, places where the middle school and the high school tend to be smaller, they tend to be much less diverse racially, ethnically and socioeconomically. They’re higher performing as a result because of the way those things correlate . . . but both for pragmatic reasons about buying a house and what we could afford and also a sense that there was a lot of virtue in having our kids go to schools that better reflected the real world that they would be entering and the diversity of the country, and that they had a lot to learn and benefit from that experience.

As Peter implied, parents’ understand that Morris is ranked lower by US News or New Jersey Monthly, compared to more homogeneous and majority white districts “where everyone is the same,” because of its diverse context—and the fact that socioeconomics are highly correlated with standardized test scores.

MSD alumni and current students view diversity as a unique advantage in preparing them for the “real world” that their peers in more homogeneous (majority white) school districts do not receive. During the focus group in which we asked white high school students to compare their experiences with students who attend majority white schools, one student said: “I feel like since we go to this school, we have a better grip on the segregation that occurs. If we were to go to Mendham, those kids would be blatantly racist without even realizing it.” A second student replied, “It is real life. Our town, the racial diversity, that’s actual life.” A third student followed up by saying, “That’s why I love it!” During this year’s high school graduation ceremony, the student government president said this about the benefits of diversity at MSD:

What we will miss most about Morristown High is the diversity. Morristown High represents more than nineteen different native languages. However, the diversity of the school runs far deeper than the color of any student’s skin or color of ancestry. Walking around the school you will find far more than the typical scholars and athletes, but also musicians, artists, filmmakers, and aspiring scientists—ultimately disrupting the high school status quo.24

According to respondents, some of the biggest benefits of diversity are to prepare students to work with students who are different than they are, and, even more importantly, to break down stereotypes and boundaries between groups. For instance, during one of the teacher focus groups, teachers spoke about an English assignment in which students were asked to research and write a report about positive Latino influences on American culture. Student assignments ranged from “struggles of being an undocumented worker, another student wrote about inventors, while others wrote about leaders, politicians and celebrities” with the goal of changing negative perceptions into positive ones. Similarly, a Latino student during a student focus group replied: “You have to break the boundaries. That’s one thing I will say. People here, once you do break that social—once you break that stereotype, it’s like, Oh, really we aren’t different. We’re actually—we’re very similar.” In so many ways, MSD students are learning how to cross cultural, racial, and socioeconomic status divides in their schools and community. These are important lessons to learn if the goal is to become more tolerant citizens in an increasingly diverse society.

The other reasons parents gave for choosing Morris, besides the diversity, are the high-quality and specialized educational programs and extracurricular activities the district has to offer. The 2015 Niche Award for Best Public High Schools ranks Morristown High School (MHS) number one for extracurricular programs in Morris County and gives it A+ for academic achievement. MHS’s course offerings are diverse and include culinary arts, broadcasting, music, and STEM—that, as one district administrator said, “continue to bring people in.”

The high school also has had notable success with its sports teams, which undeniably attract families to the district. During the 2015–16 school year, the successes include state, regional, and county accolades in sports such as golf and hockey, as well as track and field.

Additionally, the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math program, or STEM Academy, is in its fourth year and serves 150 students in grades nine through eleven. STEM students take their regular courses and then are able to take electives in such areas as Robotics, Aerospace Engineering, or Anatomy and Physiology.25 This year, STEM students on the MHS science team won first place in the county and eighth place in the state during the annual New Jersey State Science Fair competition.

Other accomplishments include the MHS Theatre Department winning a prestigious all-state award for the performance of A Christmas Carol. The department also won an inclusion and access award for including students with disabilities in all areas of theatre production.

Morristown High School also has an Olympic-size swimming pool and a live radio station. Respondents boasted that the AP test scores are “through the roof” and college-going rates are high, which they said balances out the other factors. The district’s spring 2015 newsletter boasts that eleven students were admitted to Ivy League schools, more than many of the nearby predominantly white and upper-income high schools can claim. Additionally, “50 percent of MHS seniors who applied to a four-year college were admitted to colleges rated by Baron’s Guide to Colleges as “Most Competitive” or “Highly Competitive.”26 As one white teacher exclaimed during the teacher focus group, “you’ve got something for everyone” at Morris. In fact, MSD’s mission is to “accommodate equity” by meeting every student’s needs.27

Not only that, but Morris appears to be at the forefront of resisting testing metrics as sole indicators of educational achievement. Parents and administrators appreciate that Morris puts education first, and that test prep, accountability and standards get less priority, which is not the case in many other districts. This is evident by the considerable number of families who chose to have their students opt out of the most recent state tests—in fact, nearly 90 percent of eleventh-graders opted out of the ELA exam in 2015.28 An elementary school principal, Cindy, said of the district “traditionally they don’t focus on the testing.” Instead, they focus on cultural arts and an integrated curriculum. She said they certainly want students to learn the basics and come to school motivated to learn, but they do not believe that “drill and kill” for the tests is the way to achieve that goal. One white district administrator, named Marty, who had experience working in another New Jersey district before coming to Morris, replied that in Morris the emphasis is on education and what is best for the students. He likened the educational approach that Morris takes to a “dinosaur, in a very good way”:

This school is what schools used to be like before the reform movement and all of this accountability reform where everything has to be measured and it’s the only thing that matters. It’s all about rubrics. Here, it’s all about education. The discussion is always about what’s best for the kids. That may not seem like something special, but it’s not what’s happening in schools now. Those discussions—schools are about management, control, measurement, rubrics, accountability. We do those things, but I think . . . at this place, it’s about really creating an educational environment and doing what’s best for kids.

The Morris district is very aware that it is competing with private schools for students, so it is starting to do more public relations work to share its accomplishments. Patty, a white former student and current high school parent, explained that she is helping the district reach out to alumni about their experiences in Morris for marketing purposes. She told a story about one former student she interviewed who said, “When I got to Princeton I felt just as prepared academically for my experience that would happen at Princeton, but I felt more prepared than my peers for being able to work in groups and understand and respect the differences of others.” What the district is finding is that because of their exposure to diversity, Morris graduates feel better prepared socially and academically than their college peers who went to racially and socioeconomically homogeneous districts.

Strong Community and Family Partnership with the Schools

Another reason that respondents believe the district merger for racial balance purposes worked in Morristown was because there was, and still is, a strong coalition of community, civic and religious organizations that support the work of the school district through tutoring and afterschool programs. There are also structures in place in the community within the large network of nonprofit organizations and churches that produce socially and academically positive results when issues or problems come up. This collaborative effort in the Morris district, and especially in Morristown, seems distinctive if not unique.

Building Bridges with the Schools

Substantial evidence emerged in our interviews that the schools and community are working together to help low-income students overcome challenges in school and at home and level the playing field. For example, each student in grades 6–12 is given a personal Chromebook to use in the classroom and to take home to do their homework. The district realized that some low-income students did not have access to Internet at home—making it hard to complete their assignments. Therefore, the Morris Educational Foundation raised funds for Kajeet Smartspot Mi-fi devices, which give students access to the Internet in any setting.

Another area of concern for the district is the availability of preschool for low-income families with one possibility being an expansion of MSD’s pre-K program for children with special needs. An MSD administrator, Betsy, said one of the areas that she has been working on is kindergarten-readiness and building relationships with the different preschool providers in the community. She said she has been going to the preschool centers and conducting parent workshops on what kinds of things children should be doing over the summer to build literacy skills in Spanish or English.

Betsy went on to say that her favorite program for students is the after-school tutoring program at the churches. She said this is an example of a true partnership between the schools and community:

The schools identify the kids who need the tutoring and then we provide transportation and the churches get volunteers. I go and train the volunteers to tutor the kids on what to do and what to look for and those sorts of things. The kids go for two hours a week for tutoring to these churches. So for me, that is what Morristown is about. Nobody is saying, “No, we don’t want to help.”

Betsy said that she meets with the pastors, reverends, the women who run the Sunday school who do the tutoring, and “When you talk about really what it looks like here for us day to day, that’s a great picture of how we can engage people. I don’t think that’s the same in every place.” Betsy and others in the community believe that this strong community–school connection makes for a better place to live.

A looming problem for the district, however, is figuring out the best way to deal with the growing Hispanic population. The main challenges include the need for more bilingual staff and continued improvement in outreach efforts to Hispanic families. The district is responding to the challenge by recruiting and hiring more Spanish speaking staff. The superintendent reported that since June 2015, the district hired ten bilingual teachers, and 31 percent of all new hires (counselors, administrators, and teachers) speak Spanish.

Outreach to the Hispanic Community

Respondents said that Hispanic families, particularly new immigrants from Central America, face many barriers to participating in their child’s education, with language being the biggest hurdle to overcome. Additionally, a large percentage of Hispanic students come from single-parent households, or both of their parents work, or they live with extended family members—making it difficult sometimes for caregivers to become involved in the schools. As a result of this steady influx of Hispanic families into MSD, including a group of seventy-one unaccompanied minors from Central America in 2014, the district recognized that it quickly needed to address the needs of Hispanic students. Thus, the district created a new ELL/bilingual supervisor position and filled two new social support positions—a “district outreach teacher” named Maria, and a “bilingual academic support counselor” named Teresa.

Maria’s job is to be a part-time high school teacher of Spanish and a part-time outreach worker to Hispanic parents. She is a Latina teacher who grew up in Morristown and went to the public schools. She also is on the board of the Neighborhood House, an important civic organization in Morristown that started as part of the settlement house movement many years ago and has been very involved and invested in the Hispanic community in recent years. Maria said one of the first things she did in her new position was create a database of all the parents who spoke Spanish in order to communicate with them about the schools and get them to come to Back to School Night and meet their children’s teachers. Maria pointed out that there are only 8–10 percent of students in the district who are classified as ELL. However, she found out through a home language survey that there are some Hispanic students who speak English, yet their parents speak Spanish and were not getting information in Spanish sent home. This was the population she was trying to identify because, as she explained, only a few Hispanic parents come to school events, which some may interpret as a sign that they do not care about their child’s education.

She sent out flyers, made phone calls, and did outreach to the Spanish churches, which resulted in seventy Spanish-speaking families attending Back to School Night in 2015. Maria thought this was a great success because the parents want to help, they just do not know how. She has been hearing how appreciative the parents are to get the information and have her as a point person in the school because, “I know that for the Latino community, our biggest barrier is language.” Therefore, increasing access to information and showing parents how to advocate for their children are some of her biggest priorities moving forward. Maria remains hopeful that strides are being made to improve outreach, which she believes will translate into improved achievement levels: “I really do think that, if the Latino community was fully engaged, we’d be making history for how Morristown High School got Latinos to be at the top of the whatever. Across the country, Latinos are failing.”

The broader Morristown community also is spearheading efforts to empower the Hispanic community. For example, community organizations offer programs such as “Parents as Partners,” at which school district staff meet with parents to discuss issues such as “What is a grade? What is a credit? What does a report card mean?” They also discuss how parents and guardians can access their children’s grades and attendance records online through an academic community platform, called Blackboard. The Neighborhood House, which provides after-school programming to low-income students, has hired more bilingual staff and offers various parent workshops in Spanish about child rearing and school topics. Other concerted efforts on the part of the district to bridge the divide between the schools and the Hispanic community include hiring more bilingual staff, and having all announcements and school presentations provided in Spanish via headsets.

The district also recently hired a bilingual social worker named Teresa to help high school students adjust to life in Morristown—both inside and outside of school. Teresa described what she does for students and their families:

It starts out with me with the basics: food, clothing, shelter. I’m always the one that they’re coming to if they’re not getting their free lunch. I like it that they start to know that I’m the one they can come to for that. “Oh, if you’re not getting your free lunch,” I said, “Tell your friends that if they’re not getting their free lunch and they haven’t filled out the form and they don’t know about the form, or reduced lunch, come to me because I can help them with that.” Some of them are—you know, it’s all about trying to negotiate a huge system, too. We have almost 2,000 kids. “Well, where do I go? What is the central office? Someone else called it something else to me.” It’s the language. It’s everything.

Teresa explained that it is not just the lack of education of the students, but the parents too. This makes it difficult to explain everything to them and get permission from caregivers to provide services. She estimated that it takes “ten times more time with this [unaccompanied] kid, than you spend with the average kid. It’s arduous.”

This partnership among the community, family and schools is far from perfect in some people’s eyes. However, like so many issues in Morristown there is a strong sense of hope among respondents that things can and will be improved to provide more access and opportunity and to close gaps. Illustrating this positive attitude in the district, Cindy remarked: “So I think we’ve done a good job of whatever the challenge is, okay, we’re going to take that up and not throw up our hands. That’s a very positive thing and I think because parents see that.”

Overcoming the Challenges of School Diversity

MSD is proud of its long-term commitment to diversity at the district and school levels. However, one of the biggest criticisms of the district is that, although administrators are aware of the achievement gaps and the racial/ethnic disparities in course taking, there has been a slow and uneven response to these problems. We outline below some of the challenges that diversity imposes on MSD, including racialized tracking and ability grouping, catering to white families, and meeting the language and social-emotional needs of recently arrived Hispanic immigrants. We discuss the community and student response to these problems, and how district administrators are addressing them.

The Achievement Gap and Attempts to Diversify Courses

In 2012, the perception that the district was slow to address the achievement gap issue prompted an active group of black parents to get together and confront the district. We interviewed four black parents who were part of this group, and they explained how they brought attention to the problem at HSA meetings, school board meetings, and even had regular discussions with the high school principal and superintendent. They advocated for more administrators and teachers of color in the schools, and wanted the district to track student progress and catch students early who were falling behind. Yet, as Trista, a black public school parent who was part of this group of concerned parents, stated, from the district’s perspective “they told us that it’s not something new and that they were very aware of it and that they were working on it. We just felt like they weren’t working hard enough on it.” In other words, the parents felt it was all talk and little action.