Across the United States, the vast majority of public colleges and universities that offer online education programs or courses are now relying upon external companies to do so. The services these companies—so-called online program managers (OPMs)—provide range from simply supplying the online platform through which university affiliates interact with students to all-inclusive distance-learning programs rebranded under the institution’s name, and everything in-between.1

Helping institutions initiate and expand their online programming has become a $1.5 billion industry that is expected to grow at an estimated annual rate of 35 percent in the coming years.2 In many cases, there seems little downside for schools to work with OPMs to serve and expand their population of online students—already over a quarter of the 20 million students enrolled in higher education—since most of the upfront costs associated with online learning (i.e. technology development) are shouldered by the outside company in these deals.3 As a result, schools get the opportunity to launch online programs that they would otherwise never be able to afford. Particularly in light of decreased state spending on higher education, the potential revenue stream online education represents is simply too attractive for many public institutions to pass up.4

These outside contractors may be supporting and supplying online programming effectively, but the involvement of a third-party—particularly a profit-seeking entity—in providing services so intertwined with the actual teaching and learning also presents potential risks to quality and value in the education. Specifically, the growing use of for-profit intermediaries to provide online programming at public institutions raises important questions concerning whether these agreements appropriately shield students from the profit-seeking motives of these companies, inform students about exactly who is responsible for the education they are receiving, and provide quality education that is up to the standards of institutions backed by the full faith and credit of states.

The involvement of these entities is changing the nature of public education. While the growth of OPMs has been widely reported, the contracts between these entities and their clients—generally public and nonprofit institutions—have never before been amassed and analyzed.5 Over the past eight months, The Century Foundation (TCF) has collected over one hundred of these agreements and communicated with over two hundred institutions regarding their relationships with OPMs. In analyzing these agreements, this report seeks to reveal the extent to which schools have come to rely on private companies to adapt to and adopt new technologies.

The OPM Marketplace

Michigan State University provides an example of how OPMs operate behind the scenes. The landing page for the University’s online executive development programs features the University’s logo and a picture from inside the school’s Broad College of Business. “Lead Like a Spartan,” reads a banner on the program’s website.6 It continues: “MSU’s online graduate programs instill the type of roll up your sleeves and get to work ethic sought by today’s employers.” Perusing the information available to potential students, there is no indication that an external contractor provides recruitment and marketing services, as well as course production and instructional design for many of the programs rather than the university itself or that, for each dollar these programs bring in as revenue, more than half goes to that contractor.7

And Michigan State University is far from alone; over 70 percent of the institutions or institutional consortiums that provided a relevant response to TCF’s request—84 out of the 117—contract with at least one for-profit OPM to facilitate their online programming.8

A Traditional Outsourcing Model with a Dangerous Twist

Colleges and universities—including public institutions—have long outsourced portions of their services.9 Schools often save money and enhance quality by allowing more specialized entities to provide specific sets of services, achieving otherwise unavailable economies of scale and reducing long-term employment-related costs. Outsourcing may also allow educational institutions to reapportion resources more efficiently so that staff and faculty can focus on the core educational mission of the school itself, rather than the wrap-around, non-educational services—computer servicing, facility management, food service, printing, security, etc.—that have come to be expected of postsecondary institutions.10 For example, in 2012, private investors paid $483 million to Ohio State University for a lease to operate university parking. One year later, an Ohio State accounting professor emphasized the benefits of the agreement: “Our core strength as a university is not running parking facilities. So we should focus on what we’re really good at and hire others to do what they’re really good at.”11

In many ways, OPMs are similar to these traditional outsourcing arrangements. OPM companies—such as Blackboard, Pearson Embanet, Canvas, Academic Partnerships, Education To Go, and Desire2Learn—provide expertise to institutions of higher education concerning the management and delivery of online learning that the institutions themselves have neither the resources nor interest to develop in-house. However, unlike managing dormitories or servicing cafeterias or organizing parking, the functions of OPMs are closely linked to the core educational mission of these public institutions. As a result, the quality of the services provided by OPMs has a direct bearing on the quality of the school itself and the ability of these institutions to fulfill their mission to train students and prepare them for the workforce. It’s when these OPMs—particularly for-profit entities—operate their services without proper oversight that problems can arise.

The Variety of Services and Contract Terms

In order to identify potential warning signs, it is critical to first understand the varying services that OPMs provide. The contracts TCF reviewed expose, in broad strokes, two distinct sectors of the OPM market: the first set of companies provide digital platforms where content created by university personnel is hosted; the second group is composed of OPMs that provide more program specific resources to facilitate online programming—such as enrollment specialists, course materials, or marketing strategies.

Over the past decade, the OPM industry has matured and consolidated. Blackboard acquired three of its competitors—WebCT, Elluminate, and Wimba—to become the dominant online education platform that falls into that first category, while Pearson and Wiley, two traditional education publishing powerhouses following the latter model, have both acquired up-and-coming OPMs to expand their online offerings. A variety of companies have, however, found their niches in the OPM industry by providing a specific set of services to their institutional clients.

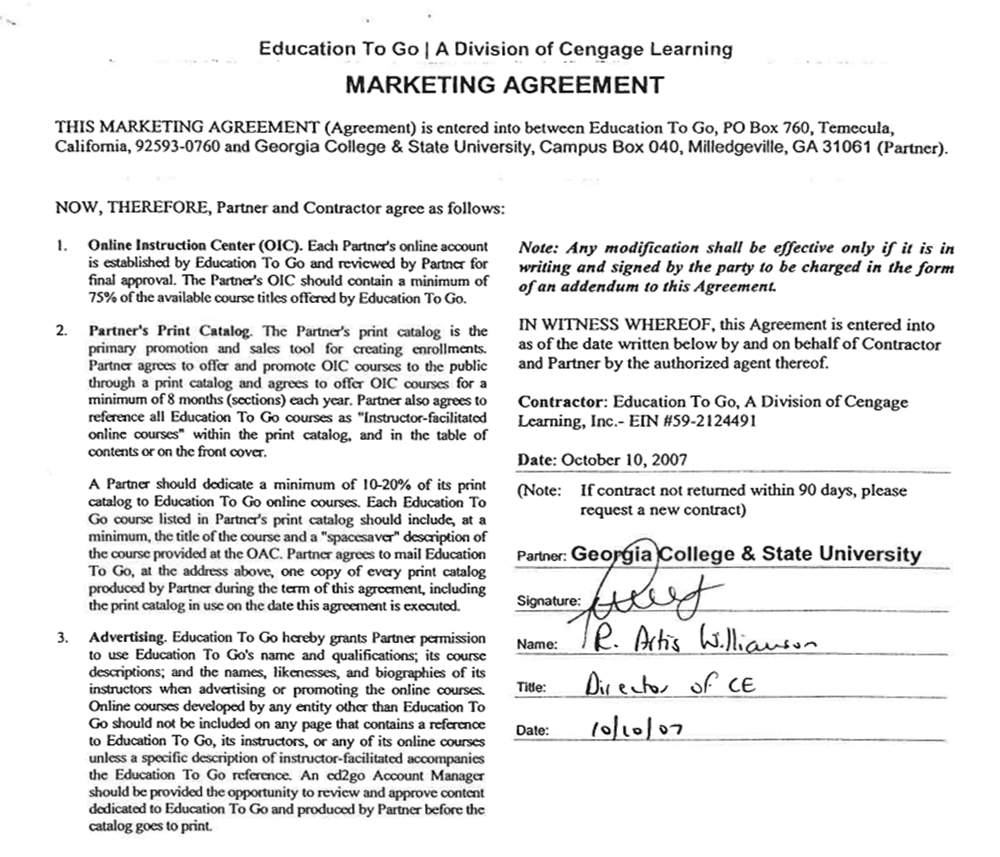

Institutional contracts with Education To Go, for example, establish a menu of courses and programs the contracting institution would like to make available to students from the company’s pre-existing digital supply. Subsequently, Education To Go and the partner institution establish wholesale and retail prices for the relevant programming, with the institution paying Education To Go the wholesale price and retaining the difference between these amounts when students, who pay the retail amount, decide to enroll. The institutions are responsible for advertising these products and, in most of the Education To Go contracts, are required to promote a set percentage of the available online programs in the school’s annual course catalogue. In other words, Education To Go makes available to institutions complete online learning opportunities and institutions make these opportunities available to students. MindEdge Learning, another OPM, has a similar agreement with Mesalands Community College.

There are, however, relatively few contracts like Education To Go’s—approximately one-eighth of the contracts reviewed utilize this all-inclusive model in which an external company provides comprehensive educational content for specific courses or programs. Much more common are agreements that outsource particular services, such as marketing or retention services, while involving University affiliates in the actual teaching process, and agreements that simply supply a digital platform upon which University affiliates provide educational material and interact with students.

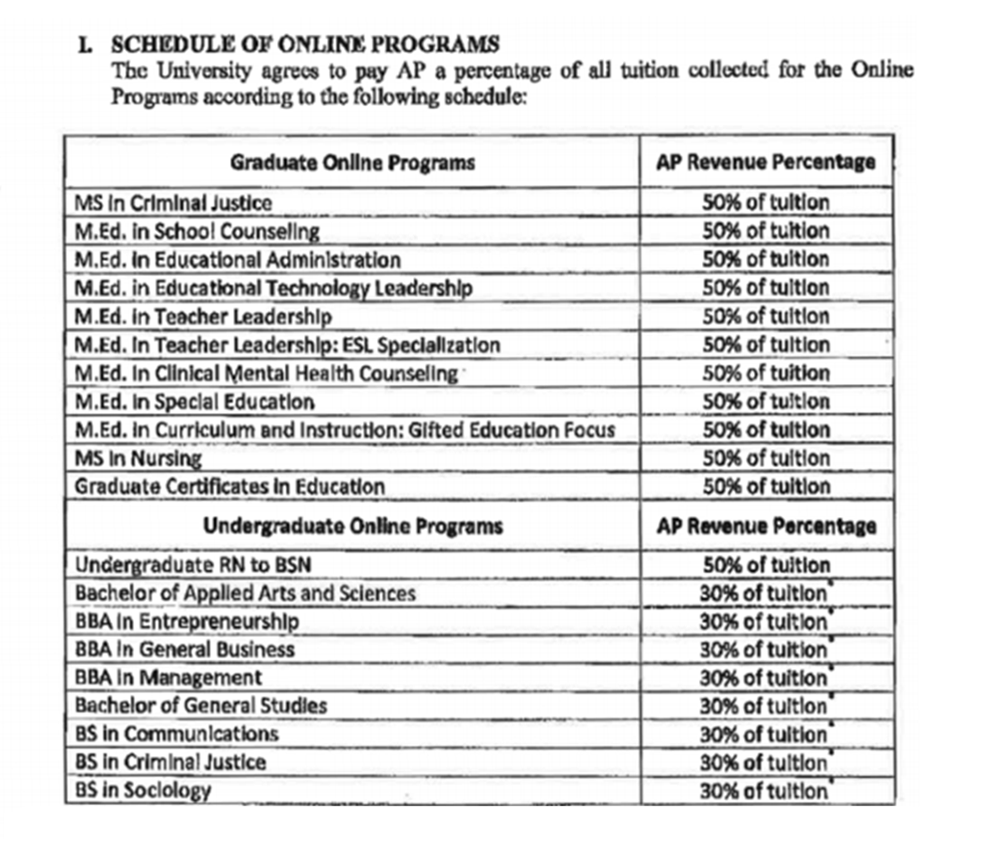

Louisiana State University (LSU), for instance, entered into a contract in 2013 with Academic Partnership (AP), through which AP provides “a team which [works] with LSU faculty in converting course content to an online format, [reviewing] existing course, and [providing] recommendations to enhance online offerings,” in addition to supplying “competitive market analysis,” “marketing and recruitment,” and “student enrollment, retention, and support” services. LSU is, however, responsible for the content of the programming, in addition to student assessment, advising, and teaching. For these services, the University remits to AP 50 percent of the tuition for the distance learning programs covered under the agreement, up to $5,800,000.

AP’s 2016 contract with Eastern Michigan University implements a similar model, though emphasizes that the OPM will be responsible for supplying “enrollment specialist representatives” who “will serve as a primary point of contact for all prospective Students for the Online Programs.” Not only will these representatives initiate contact with potential students, but they will also help them complete applications and “provide Student support and retention services, including, but not limited to…following up with Students periodically through graduation; referring Students to University resources if academic questions persist; welcoming new Students and providing upcoming registration dates and/or deadlines; re-engaging inactive Students; and reminding Students of upcoming start dates, registration deadlines and payment deadlines.” As a result of this contract, the University is set to launch four new online programs this summer and another ten in the fall.

The role of OPMs in this model also extends beyond those services related directly to students. For example, Everspring’s contract with Auburn University tasks the company with advising the university “on individual state requirements for compliance standards for obtaining operating approvals.” In Coursera’s agreement with the Tennessee Board of Regents, the contractor assumed responsibility for tracking student learning.

The thirty-five reviewed contracts concerning services contracted from Blackboard and Desire2Learn are more limited in scope, providing institutions access to proprietary technology that allows faculty members to communicate and interact with students, rather than any particular educational content. Schools or their affiliates pay a set price to use these platforms depending on the exact resources purchased and an approximate number of students who will utilize these services. Central Texas College, for example, entered into a contract with Blackboard in 2014 through which the college agreed to pay almost five million dollars to the company over the subsequent five years.

|

Table I: Characteristics of the Most Common OPMs Among Contracts Reviewed |

||||

| OPM | Services | Common Payment Structure12 | Number of Contracts Reviewed | Institutional Clients |

| Blackboard, Inc. | Online education platform | Lump sum | 28 | Eastern New Mexico University; Framingham State University; Grand Rapids Community College; Idaho State Board of Education; Institute for American Indian Arts; Kentucky Community and Technical College System; Luna Community College; Marshall University; Mississippi Community Colleges; Montana State University; New Mexico Higher Education Department; New Mexico State University; Northern Illinois University; Texas A&M; University of Alabama; University of Idaho; University of New Mexico; University of North Texas; University of Southern Mississippi; University of Texas; Washington State Board for Community & Technical Colleges; Washington State University; Western New Mexico University; Blue Mountain Community College; University of Vermont; Cleveland State University |

| Canvas by Instructure | Online education platform | Lump sum | 12 | Michigan Technological University; Mississippi Community Colleges; New Mexico Junior College; New Mexico Military Institute; New Mexico State University; Ozarks Technical Community College; Rutgers University; Texas A&M; Victoria College; University of Mary Washington; Washington State Board for Community & Technical Colleges; Blue Mountain Community College |

| Pearson Education | Student recruitment, curricular design, student support, education technology | Revenue share | 11 | University of Texas-El Paso; Ocean County College; Washington State University; Arizona State University; Kentucky Community and Technical College System; Eastern Kentucky University; University of Florida; University of Illinois; New Jersey Institute of Technology; Ohio University; University of Cincinnati |

| Academic Partnerships | Student recruitment, curricular design, curricular production, faculty support, student support | Revenue share | 7 | University of Texas; Louisiana State University; Eastern Michigan University; University of Cincinnati; Lamar University; University of Rhode Island; University of North Carolina-Wilmington |

| D2L | Online education platform | Lump sum | 7 | Mississippi Community Colleges; Montana University System; New Mexico Highlands University; Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education; University of Arizona; College System of Tennessee; Minnesota State Colleges and Universities |

| Education to Go | Complete course | Revenue share | 7 | Highland Community College; Georgia College and State University; Grand Rapids Community College; Los Angeles Community College District; Montgomery County Community College; University of Vermont; Victoria College |

| Coursera | Online education platform | Revenue share | 5 | College System of Tennessee; Michigan State University; University of Arizona; University of Florida; University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill |

| Bisk Education | Student recruitment, curricular design, faculty support, online education platform, student support | Revenue share | 3 | University of Florida; Michigan State University; University of Vermont |

| Everspring Partners, Inc. | Student recruitment, curricular design, faculty support, student support | Revenue share | 3 | Kent State University; Auburn University; University of Kansas |

| All Campus | Student recruitment, student support, regulatory guidance | Revenue share | 2 | Purdue University; University of Florida |

| Apollidon Learning | Student recruitment, curricular design, curricular production, faculty support, student support, regulatory guidance | Revenue share | 2 | University of Florida; American Distance Education Consortium |

| Wiley Education Services | Student recruitment, faculty support, online education platform, regulatory guidance | Revenue share | 2 | Purdue University; University of Florida |

| 2U, Inc. | Student recruitment, curricular design, curricular production, faculty support, online education platform, student support | Revenue share | 2 | University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill; University of California-Berkeley |

|

Source: Data collected by author. |

||||

One responsibility that institutions rarely hand over to these companies is admissions. Though OPMs are frequently assigned to help prospective students complete applications and increase the lead-to-enrollment conversion, the actual decision whether or not to enroll a student generally remains with the school itself. Exceptions are uniformly for programs in which students can immediately enroll upon signing up and, generally, paying; in other words, programs for which there are no prerequisites and no admissions decision is ever made. These programs include Purdue University’s contract with The College Network, Inc. (TCN) and Boise State University’s partnerships with Harvard Business School’s HBX unit.

Through Purdue’s ongoing partnership with TCN, which began in 2009, the company hosts, markets, and promotes Purdue’s Lean Six Sigma three certificate programs, which are based upon the Lean Six Sigma methodology to reduce waste and inefficient variation within the workplace. The university is largely responsible for the content of the programs, but TCN employees help convert the relevant coursework to the online learning environment and to “sell the Purdue courses and programs.” Purdue employees or faculty members have minimal interaction with students, with TCN serving as their primary point of contact. The financial agreement between the two parties has changed some over the past eight years, but the most recent iteration sends between 50 and 60 percent of the total sale amount into Purdue coffers, depending on on the source of the customer, and the remaining funds to TCN. Certificates start at $2,100.

Financial Arrangements Between OPMs and Schools

In line with this broad distinction between OPMs that provide digital platforms and those that provide more tailored services, these companies also generally utilize one of two payment structures.

Companies that provide platforms through which a large and sometimes unlimited number of students or instructors can take advantage of online resources, such as Blackboard, generally charge schools a set price for particular services. Like Central Texas College, Texas A&M University signed a contract with Blackboard in January 2016 outlining about $1.3 million worth of services to be delivered over the subsequent two and half years. These services primarily consist of access to Blackboard Collaborate—an online learning system with capabilities to facilitate both synchronous and asynchronous educational delivery—for between 50,001 and 74,000 students. As with all of the Blackboard contracts reviewed, the institution itself remains exclusively responsible for the content of courses, assessment, student tracking, and enrollment management. About forty percent of agreements reviewed in this analysis use this payment system.

Alternately, the fee structure for OPMs that provide services related to educational content, recruitment services, or counseling, generally establishes a set percentage of the online program’s revenue or tuition, or establishes a set fee per enrollee. In other words, the amount ultimately owed to the contracting OPM is linked to use. This latter model is also present in about forty percent of the contracts reviewed with the percentage of revenue pocketed by the OPM ranging from 10 to 80 percent.

The University of North Carolina, Wilmington, for instance, entered into a contract with AP in 2013 “in connection with the development, maintenance, and marketing” of the school’s online Master’s in Elementary Education and Bachelor’s in Nursing. Under the terms of the agreement, AP is the exclusive marketer of these programs, provides assistance to University faculty as they become accustomed to teaching for an online audience, contacts potential students through “enrollment specialist representatives,” and supplies student support services, among other responsibilities. For these services, AP earns 55 percent of tuition for the first 18 months that the Master’s is offered, 50 percent after this initial period, and 50 percent of all tuition for the Bachelor’s program. The agreements reviewed indicate that these revenue sharing percentages are fairly standard among OPMs, like AP and Pearson, that provide substantial assistance in facilitating distance learning programs.

Another pricing model that varies based upon use is that of Classmate. Between 2004 and 2010, the University of Texas System Office paid approximately $100,000 to Classmate for online access to “learning materials” associated with particular lessons in geometry and algebra courses. The Kentucky Community and Technical College System has entered into a similar agreement with Brainfuse, through which the company provides online tutoring services to students at participating schools for $22.50 per hour.

There also exist many hybrid payment structures that blend elements of these strategies. Sometimes different fee structures are utilized within a single agreement depending on the particular product. For example, Eastern Kentucky University paid Compass Knowledge Group $75,000 as a launch fee for a Master of Science in Safety, Security, and Emergency Management and related certificates in 2010. In addition, however, the company receives 50 percent of the instructional fees associated with the program. In other agreements, the cost is set but based upon an estimate of the number of students who will take advantage of the contractual arrangement and is subject to change.

Non-Institutional Actors Entering OPM Agreements

Institutions are not the only ones entering into these contracts. Some statewide community college systems and third-party consortiums are also partaking on behalf of their members. For example, schools such as Oregon State University, Pennsylvania State University, and Washington State University entered into an agreement with Apollidon through the American Distance Education Consortium (ADEC), a nonprofit “conceived and developed to promote the creation and provision of high quality, economical distance education programs and services…through the most appropriate information technologies available.”13 As a result of this agreement, Apollidon has assumed responsibility for market research, as well as creating and maintaining “effective marketing” for certain online programs at member institutions.

Risks Posed by the OPM Model

Public college and universities are under the control of the state and largely—though decreasingly—funded by taxpayers. Like all governmental and nonprofit institutions, public institutions of higher education need money to pursue their educational missions, but their ultimate goal is not financial. These colleges and universities have no owners or investors hoping to turn a profit, nor are those with at the helm of the institution—the directors or trustees—able to sell stock or benefit financially by, for example, increasing tuition or cutting instructor pay. In contrast, for-profit, private OPMs face no such restrictions; owners and investors are able to pocket whatever funds are not spent, and those in charge have a financial stake in the entity’s operations. This often makes owner-operated educational companies more aggressive and singly-focused on maximizing return than their public or nonprofit counterparts.14

Prioritizing Dollars Over Learning

The involvement of OPMs in the establishment and growth of online educational opportunities at public institutions exposes consumers to the financial interests of decision-makers, interests that would not exist if exclusively public or nonprofit institutions were involved in providing these distance learning programs. Driven by the desire and need to make money for investors or owners, those to whom executives are held accountable, these companies may prioritize profit over the interests of online students, to whom they owe no loyalty, financial or otherwise.

These companies may prioritize profit over the interests of online students, to whom they owe no loyalty, financial or otherwise.

These financial incentives sometimes lead to more efficient and less expensive options for consumers but higher education exhibits what Henry Hansmann, in his seminal article on nonprofit enterprises, called contract failure. When it is difficult to evaluate the quality of the promised or provided product—as it is with education at any level—a profit seeker can more easily charge too much or deliver inferior goods or services. “As a consequence,” says Hansmann, “consumer welfare may suffer considerably.”15 For-profit OPMs—especially those that exert a high degree of autonomy regarding online programming—expose consumers to the same risks as for-profit colleges however, because they are operating on behalf of public institutions, none of the protections in place to prevent abuse by the proprietary education industry protect these students.This blindspot leaves consumers vulnerable.

The revenue-sharing model of fee structures utilized by OPMs such as AP, Pearson, Wiley, and 2U is particularly problematic because it establishes clear financial incentives for OPMs to make online programs larger and more expensive for students, while simultaneously reducing expenditures. In other words, these companies have a financial interest in pressing public institutions to enroll as many students as possible for as high a price as possible, regardless of how well students are prepared for the specific educational program or the quality of the program itself. And, since many of these OPMs play a significant role in developing and delivering these programs, the companies also have an incentive and the ability to cut production costs and, potentially, quality. While individual administrators and faculty members at the public institutions can rebuff these attempts when establishing enrollment targets and admissions criteria, these interests—driven by the governance structure of for-profit business—will nevertheless persist.

Leaving Students in the Dark

This potential prioritization of dollars over learning is particularly risky because the involvement of these external entities is rarely apparent to consumers. As a result, students are likely not aware that it is actually Bisk, for example, rather than Eastern Michigan University, that is largely responsible for the school’s Business Analytics Certificate Program. In fact, none of the information made available to students by public institutions reviewed during this analysis names an OPM contractor explicitly and very few institutions acknowledge that they work with an outside partner. Louisiana State University’s agreement with AP goes so far as to explicitly request that marketing materials created by the OPM “‘look and feel’ so that they blend with LSU’s existing brand identity.” Students are therefore likely assume—incorrectly—that a school’s online programming is entirely sponsored, created, and managed in-house. In addition to allowing OPMs to capitalize on the brand recognition of well-known public institutions, this arrangement also puts at risk the schools’ reputations. If OPMs are successful in increasing the size or decreasing the quality of the distance learning programs to boost short-term profits, the institutions themselves will likely be held responsible for these faults in the public eye.

Exposing Students’ Information to Marketers

Another significant concern arising from the involvement of these corporate entities is privacy. Potential students—known in the marketing world as leads—form the foundation of the OPM business model since many of these companies are responsible for marketing and recruitment. Unlike a single institution however, for which a new set of leads must generated for each unique program, OPMs can use and reuse leads because they often serve multiple, sometimes competing, online programs. As a result, information concerning potential students—contact information, academic interests, educational background—is invaluable to OPMs as they seek to enroll and retain students. Since many of these OPMs are also paid based upon the program’s revenue or tuition, these leads are not only important to meet the terms of the agreement, but also to turn a profit.

Information concerning potential students—contact information, academic interests, educational background—is invaluable to OPMs as they seek to enroll and retain students.

Indicative of just how valuable these leads are to OPMs, 2U paid the University of California-Berkeley $4.2 million in 2014 for the permission to ask applicants, including those who were denied entry into the Berkeley program, if they would like to learn more about another, similar program offered by 2U and Southern Methodist University. Similar clauses exist in other agreements. Through a 2015 amendment to the service agreement between the University of North Carolina and 2tor—the predecessor of 2U—the company has since been allowed to engage in “targeted marketing…about any or all Competitive Program(s) and/or Competitive Program School(s) to Program applicants denied admission into the Program.”

Lamar University’s contract with AP and the University of Vermont’s agreement with Bisk include similar statements. AP is permitted to “utilize the information of denied applicants to contact them to provide information on other education opportunities at institutions that also allow their denied applicants to receive information on other educational opportunities.” The University of Vermont (UVM) “agrees that Bisk shall have the right to market and advertise UVM programs together with other university programs through and with the University Alliance, a Bisk brand, and therefore UVM understands and agrees that Programs students and prospects may be provided with information on other University Alliance offerings.”

Contracts granting OPMs explicit permission to reuse leads are fairly rare among the agreements reviewed, however the majority are entirely silent on the matter. Either implicitly or explicitly granting these contractors the ability to use leads to steer students towards programs other than those they originally indicated interest expands the risks presented by these entities to consumers. Seeking to maximize profit, proprietary OPMs may employ some of the same abusive marketing practices that have plagued the for-profit college industry or sell these leads to other companies that may do so. Operating on behalf of a public institution, these companies may be able to earn the trust of, and therefore collect and utilize more information from, potential students than would otherwise be possible.

Some of the contracts reviewed do however affirmatively protect information collected related to students or potential students. For example, Ohio University’s 2008 contract with Embanet—now owned by Pearson—includes student information in its definition of confidential information and forbids the use of confidential information from either party “for any purpose whatsoever except as expressly permitted by [the] Agreement.” Michigan Technological University’s contract with Canvas does so as well, indicating “all information, data, results, plans, sketches, texts, files, links, images, photos, videos, audio files, notes, or other materials uploaded under Customer’s account in the Service remains the sole property of Customer.” Most other Pearson and Canvas contracts reviewed include similar privacy requirements. Other OPMs, such as Everspring, are simply prevented from selling leads to other universities or entities.

Rethinking Public Education

The significant involvement of private, external, for-profit companies in the adoption and use of new technologies to promote public online education calls into question what exactly about public education makes it public. If AP recruits a student, takes the lead in designing their distance learning program, supplies the online platform upon which they interact, and earns half or more of their tuition, should that student’s degree or certificate say the University of Texas, or AP? What about if Education to Go or another outside company supplies all of the educational materials?

In these circumstances, the difference between public and proprietary—a distinction central to understanding the governance and interests of these entities—becomes murky. State and federal officials have long recognized that inserting a profit motive into the education marketplace represents a particular threat to consumers that should be moderated by regulation to keep these interests in check. If an OPM is the chief decision-maker in operating and promoting an online program on behalf of a public institution, should that program be held to to regulatory standards for public or for-profit institutions? At present, these programs are evading oversight from both sides, lacking the internal oversight that comes from a nonprofit or public structure and the governmental supervision that comes from operating a for-profit school. This leaves consumers vulnerable.

If institutions—public and nonprofit alike—are not careful to monitor these contractors, students and taxpayers who thought they were working with a relatively safe public institution may find that they have been taken advantage of by a for-profit company.

OPMs are a relatively new phenomenon that, so far, have not erupted into a major scandal. However, as the marketplace stabilizes and online education becomes more competitive, these proprietary companies will likely look for new methods to increase revenue. If institutions—public and nonprofit alike—are not careful to monitor these contractors, students and taxpayers who thought they were working with a relatively safe public institution may find that they have been taken advantage of by a for-profit company. More so than other contracting arrangements, OPMs represent the outsourcing of the core educational mission of public institutions of higher education, threatening the consumer-minded focus that results from the public control of schools.

Contracts Reviewed Between Schools and OPMs

ADEC and Apollidon

Alabama State University and Kaplan

Albany State University and LearningHouse

Arizona State University and Pearson

Auburn University and Everspring

Blue Mountain Community College and Blackboard

Blue Mountain Community College and Canvas

Blue Mountain Community College and TPC

Boise State University and HBX

Central New Mexico Community College and Blackboard

Central Texas College and Blackboard

Cleveland State University and Blackboard

College System of Tennessee and Coursera

College System of Tennessee and D2L

Eastern Kentucky University and Pearson

Eastern Michigan University and AP

Eastern New Mexico University and Blackboard

Florida State University and Keypath

Framingham State University and Blackboard

Georgia College and State University and Ed2Go

Grand Rapids Community College and Blackboard

Grand Rapids Community College and Ed2Go

Highland Community College and Ed2Go

Idaho State Board of Education and Blackboard

Institute for American Indian Arts and Blackboard

Kent State University and Everspring

Kentucky Community and Technical College System and Blackboard

Kentucky Community and Technical College System and Cengage

Kentucky Community and Technical College System and Civitas

Kentucky Community and Technical College System and Pearson

Lamar University and AP

Los Angeles Community College District and Ed2Go

Louisiana State University and AP

Luna Community College and Blackboard

Marshall University and Blackboard

Mesalands Community College and MindEdge

Michigan State University and Bisk

Michigan State University and Coursera

Michigan Technological University and Canvas

Minnesota State Colleges and Universities and D2L

Mississippi Community Colleges and Blackboard

Mississippi Community Colleges and Canvas

Mississippi Community Colleges and D2L

Montana State University and Blackboard

Montana University System and D2L

Montgomery County Community College and Ed2Go

New Jersey Institute of Technology and Pearson

New Mexico Higher Education Department and Blackboard

New Mexico Highlands University and D2L

New Mexico Junior College and Canvas

New Mexico Military Institute and Canvas

New Mexico State University and Blackboard

New Mexico State University and Canvas

New Mexico State University and Centra

North Carolina Community Colleges and Remote Learner

Northern Illinois University and Blackboard

Ocean County College and Pearson

Ohio University and Pearson

Ozarks Technical Community College and Canvas

Pasadena City College and Smart Sparrow

Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education and D2L

Purdue University and All Campus

Purdue University and Wiley

Purdue University and College Network

Rutgers University and Canvas

Texas A & M and Blackboard

Texas A & M and Canvas

Texas A & M and iLaw

University of Alabama and Blackboard

University of Arizona and Coursera

University of Arizona and D2L

University of California-Berkeley and 2U

University of Cincinnati and AP

University of Cincinnati and Pearson

University of Florida and 352

University of Florida and All Campus

University of Florida and Apollidon

University of Florida and Bisk

University of Florida and CEN

University of Florida and Coursera

University of Florida and Wiley

University of Florida and Pearson

University of Florida and New Horizons

University of Idaho and Blackboard

University of Idaho and NetLearning

University of Illinois and Pearson

University of Kansas and Everspring

University of Mary Washington and Canvas

University of New Mexico and Blackboard

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and 2U

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Coursera

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Time

University of North Carolina Wilmington and AP

University of North Texas and Blackboard

University of Rhode Island and AP

University of Southern Mississippi and Blackboard

University of Texas and AP

University of Texas and AliveTek

University of Texas and Big Tomorrow

University of Texas and Blackboard

University of Texas and Brightleaf

University of Texas and Classmate

University of Texas and CAE

University of Texas and Elephant Productions

University of Texas and Enspire

University of Texas-El Paso and Pearson

University of Vermont and Bisk

University of Vermont and Blackboard

University of Vermont and Ed2Go

Victoria College and Canvas

Victoria College and Ed2Go

Victoria College and Monterey Institution of Technology

Washington State Board for Community & Technical Colleges and Blackboard

Washington State Board for Community & Technical Colleges and Canvas

Washington State University and ANGEL Learning

Washington State University and Blackboard

Washington State University and Pearson

Washington State University and National Repository of Online Courses

Western New Mexico University and Blackboard

CORRECTION: As the Tennessee Board of Regents’ contract with Coursera, which expired in 2014, is no longer active, the sentence referring to said contract has been adjusted as of August 24, 2017 to clarify that the contractor assumed responsibility for tracking student learning (an earlier version of the report used the present tense).

Notes

- These companies are also called learning management systems (LMSs). The market for these services has developed so quickly that there is not a clear distinction between these terms or widely-accepted definitions. For the purposes of this research, the term OPM will refer to any company that facilitates online educational programming; it does not include contractors that provide online resources—such as training programs, grading systems, or enrollment management—to schools.

- Vivek Kamath, “Observations on Online Program Management,” Tyton Partners, January 26, 2015, http://tytonpartners.com/library/observations-on-online-program-management/.

- National Center on Education Statistics, “Distance Learning,” https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=80, accessed May 31, 2017.

- See “Federal and State Funding of Higher Education,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, June 11, 2015, http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2015/06/federal-and-state-funding-of-higher-education.

- Derek Newton, “How Companies Profit Off Education at Nonprofit Schools,” The Atlantic, June 7, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/06/for-profit-companies-nonprofit-colleges/485930/.

- Michigan State University, “Executive Development Programs,” https://www.michiganstateuniversityonline.com/lp/all/career/all_worldclasseducation_1408/?campaignid=70161000001ClzJAAS&vid=2109937&mkwid=s_dc&pcrid=192662101627&pmt=b&pkw=michigan%20%2Bstate%20%2Bonline&gclid=CP6PiPSQ4dQCFZiEswodYPwH-w, accessed June 28, 2017.

- A link to Michigan State University’s contract with an OPM—as well as links to all of the agreements reviewed in the course of this analysis—can be found at the bottom of this report. Each of the documents provided includes every agreement between that particular institution and company. For example, if there is a revised or more recent agreement that replaced an older version, these two documents can be found using the same link.

- The original list of public institutions contacted was composed of a somewhat random selection of public institutions across the country. The flagship public institution of higher education in each state was included, as well as at least one community college in each state. Other schools were included randomly.

- On the rise of colleges and universities outsourcing institutions functions, see Scott Carlson, “The Outsourced College,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, February 29, 2016, http://www.chronicle.com/article/The-Outsourced-College/235445.

- Mary F. Bushman and John E. Dean, “Outsourcing of non-mission critical functions: A solution to the rising cost of college attendance” in Course Corrections, College Costs, October 2005, https://folio.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/10244/276/Collegecosts_Oct2005.pdf. Also see, for example, Ronda Kaysen, “Public College, Private Dorm,” New York Times, January 24, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/25/realestate/commercial/public-college-private-dorm.html.

- Kirsten Mitchell, “The 50-year agreement: OSU’s $483M parking deal stands alone among other schools after year 1,” The Lantern, December 19, 2013, http://thelantern.com/2013/12/50-year-agreement-osus-483m-parking-deal-stands-alone-among-schools-year-1/.

- The distinction between these pricing structures is whether or not the contracting party agrees to an exact price for the services provided upon signing the contract. Contracts labelled as “revenue share” include both those that charge institutions a set percentage of gross revenue or tuition and those that establish a particular fee per student.

- American Distance Education Consortium, http://adec.edu/, accessed July 6, 2017.

- Robert Shireman, “The For-Profit College Story: Scandal, Regulate, Forget, Repeat,” The Century Foundation, January 24, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/profit-college-story-scandal-regulate-forget-repeat/.

- Henry B. Hansmann, “The Role of Nonprofit Enterprise,” The Yale Law Journal 89, no. 5 (1980): 385-902, https://law.yale.edu/system/files/documents/pdf/Faculty/HansmannTheRoleofNonprofitEnterprise.pdf.