Economic insecurity has been a hallmark of working families’ lives in the twenty-first century. Memories of the Great Recession—when unemployment reached its highest level in generations—are still fresh in the American consciousness. Workers who are laid off experience longer durations of unemployment than in previous economic eras, and even when they find work, they struggle to get back to their prior wage. Americans from all walks of life feel they can no longer count on steady forty-hour-per-week jobs. Workers in low-wage service industries can have their schedule changed on a weekly or even daily basis. There is rising national awareness of the independent workforce of freelancers and the contingent workforce of on-call and on-demand workers, including an increasing number working in the so-called “gig economy.” While these workers may gain flexibility, it comes at the price of economic stability.

So in addition to unemployment, many workers are suffering through unstable earnings and wages. Economic anxiety has outlived the Great Recession, particularly among young workers and workers with less than a college degree who have struggled to maintain steady living wage employment. The economy was the top concern among voters in 2016, despite the longest economic recovery in the post World War II period. Clearly something is fundamentally wrong with the earnings and economic experiences of working Americans—requiring new thinking and policy responses that outlast recessionary periods.

Key policy responses to this challenge have included stimulating the economy to bolster full-time employment and enacting stronger labor regulation to encourage fair scheduling and better standards overall.1 In addition, there has been an interest in applying a social insurance approach not just to unemployment but to wages and their instability. President Obama has proposed the development of a wage insurance program, but it is limited to those individuals who were at a position for more than three years before they were laid off. A recent examination of ways to apply the wage insurance concept to volatility among freelancers and the gig economy concluded that “wage insurance may not be suitable as a long-term support system for 1099 workers.2”

This report seeks to expand the conversation about the type of earnings insurance that could be provided to families through the unemployment insurance system, the nation’s first responder to economic distress.

Findings and Recommendations

A new analysis of Census data presented in this report finds that earnings volatility is widespread in the post Great Recession economy:

- During the period of 2008–2013, three out of five prime earners (the top earners in the household) experienced at some point a 50 percent drop in their month-to-month earnings.

- For the typical worker, the average difference between pairs of months selected from a five-year period is $2,300–$2,600.

- Workers in contingent work arrangements, (freelance, self-employed, temporary, on-call, or otherwise nontraditional workforce—including but not limited to gig economy employment like Uber)—experience nearly twice as much earnings volatility as standard workers.

The existing unemployment insurance system provides a vehicle to meet the needs of those with unstable employment. This report delves into specific reforms that could be piloted separately as stand-alone reforms, or as part of a comprehensive overhaul of the UI program such as one laid out by the Center for American Progress, Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality and the National Employment Law Project.3 This report builds on prior research by National Employment Law Project and the Center on Law and Social Policy that looked at a variety of unemployment insurance (UI) policies that could address workers with erratic schedules.4 The three reforms this report analyzes are below. The recommendations echo suggestions for improved unemployment insurance for involuntary part-time workers recently suggested by the Economic Policy Institute.5

Partial Unemployment Benefits

The first policy examined is partial unemployment benefits. All states provide “partial unemployment benefits” to underemployed workers who have had a reduction in hours or can only find part-time work after being laid off from a full time job. These benefits can either make up for lost income caused by reductions in hours, or in the case of workers who have been laid off, encourage them to stay in the labor market even if they can’t find full-time work. These benefits are calculated as a percentage of the full unemployment insurance benefit for which those workers would be eligible. The report finds that the accessibility and generosity of these provisions vary widely by state. The penetration of partial UI claims ranges from a low of 2.4 percent of all UI claims in Louisiana to a maximum of 23.1 percent in Montana. For a worker whose hours are cut from full-time to part-time, ten states would replace half of their lost earnings while fourteen states would provide no benefits at all. To improve the effectiveness of partial unemployment benefits, the report recommends that:

- States can act to make partial unemployment benefits a meaningful response to earnings instability without any change to federal law.

- States should provide partial benefits to any worker earning less than 150 percent of the weekly benefit amount they would qualify for if they were laid off (this standard or better has been adopted by Connecticut, Delaware, Idaho, Michigan, Montana, and Vermont).6 These states pay more than twice as many partial UI claims as the 30 states that only provide benefits to workers who earn less than 100 percent of their weekly benefit amount.

- States should make administrative improvements, including allowing periodic submission of pay documentation instead of weekly reports, that would greatly facilitate use of partial benefits.

- The federal government could encourage states to adopt this standard by providing federal funding to states during a recession but only to those states that meet the minimum federal standard outlined above.

This report recommends two additional UI pilot programs to assess additional ways to address earnings instability—a schedule insurance pilot, and a freelance worker pilot.

Schedule Insurance Pilot Program

The current work-sharing program provides a special form of partial unemployment benefits that are designed to prevent layoffs. A typical work-sharing plan would cut the hours of five employees by one day per week instead of laying off one work. These newly part-time workers are compensated for part of the earnings loss with a partial unemployment payment pro-rated by the numbers of days per week lost.

Our schedule insurance proposal would extend the current work-sharing program, designed to prevent layoffs, into a program that would help employers retain experienced workers by providing a prorated unemployment benefit when hours are temporarily reduced.

Our schedule insurance proposal would extend the current work-sharing program, designed to prevent layoffs, into a program that would help employers retain experienced workers by providing a prorated unemployment benefit when hours are temporarily reduced. Under this proposal, if a covered employee scheduled for thirty-five hours of work has a seven-hour shift cancelled, the individual would receive a schedule insurance benefit equal to 20 percent of what s/he would receive for a full week of UI benefits. Schedule insurance benefits would only be available to those employers who normally provide employees with at least thirty-two hours of work per week. Firms that sign a schedule insurance agreement could qualify their covered workers for up to eight weeks of schedule insurance benefits every six months. Like other UI benefits, schedule insurance benefits would be financed through the experience rating system with safeguards to insure the effective recoupment of costs from each participating employer.

Freelance Worker Pilot Program

Freelance workers who earn their income as independent contractors and not employees are not eligible for UI for freelancers benefits. This leaves individuals with the most volatile earnings with no social insurance cushion. While traditionally, there have been significant structural barriers to insuring freelance workers—including the assumption that freelancers can decide on when they work and thus the UI program could not determine if they are truly involuntarily unemployed—the growing attention on the independent workforce calls for a test of the viability of approaches to covering freelancers with UI benefits.

…The growing attention on the independent workforce calls for a test of the viability of approaches to covering freelancers with UI benefits.

The report proposes a pilot program that would test how freelancers would react to unemployment insurance eligibility in terms of their paying premiums, collecting benefits and earnings impact. Our proposal would provide up to thirteen weeks of UI benefits to experienced freelancers who pay into the UI system for a year, and experience a temporary decline in their self-employment income (60 percent or more drop from their regular income) despite documented efforts to continue their business. The pilot would also the test the ability of nonprofit or governmental entrepreneurial assistance programs to serve as intermediaries who could determine the eligibility of participants for the program, and to provide networking services and other forms of entrepreneurial assistance to kick start their freelancing businesses. The participation of these type of programs could provide a viable approach to assessing freelancer eligibility and assisting them in stabilizing their earnings. While federal funding would be needed for a large scale pilot, smaller aspects of this pilot program could be studied with smaller investments.

Section 1: Earnings Volatility in the Post-Recession Economy

To date, few studies have measured the extent of income instability post-Recession; the most prominent papers in the literature tend to have their cutoffs in the mid-2000s. Few would argue that the American economy today is the same as it was prior to the 2007–2009 financial crisis—not only because of the dramatic, and in some cases, traumatic, influences of that event, but also given recent innovations in the labor market, including increased levels of education, older retirement ages, eroding labor market protections, and continued technological advances, perhaps best exemplified by the expansion of non-traditional work arrangements in the so-called “gig” economy. While the scholarly literature on earnings volatility is characterized by mixed findings, emerging research indicates that these post-recession trends are creating an increasingly unstable work experience for many in the workforce.

- Unpredictable scheduling is the norm in many low-wage hourly jobs. A New York Times exposé of Starbucks shed light on the use of sophisticated just-in-time scheduling technology to allocate hourly workers to minimize costs in ways that caused severe stress on their workforce.7 Along similar lines, a detailed examination by Professor Susan Lambert and her colleagues found that more than two out of five early career adults (ages 26–32) working in hourly jobs report that they find out “when they will need to work,” one week or less before the upcoming work week. On average, these hourly workers report that their schedules vary by 40 percent per month.8 New research from sociologist Ryan Finnigan found that from 2008 to 2013, almost 40 percent of workers reported that their schedules varied by up to 29 percent from the period immediately before the recession (2004–2007).9

- Involuntary part-time unemployment persisting. A recent in-depth look at involuntary part-time unemployment (those who want to work full-time but can only find part-time work) has increased to unprecedented levels during an economic recovery.10 7.8 percent of retail workers are employed in involuntary part-time employment, up from 3.4 percent before the recession. Similarly, 10.4 percent of hospitality workers are involuntarily employed in part-time jobs, up from 3.6 percent in 2007.

- There is growth in contingent work. The government has not measured the percent of the workforce in contingent jobs since 2005. However, a recent representative survey replicating that measure which includes independent contractors, on-call workers, contract workers, and those employed by temporary agencies suggests a large increase between 2005 and 2015 from 10.1 percent of the workforce in 2005 to 15.8 percent in 2015.11 Much of the recent interest in contingent work has focused on the rise of on-demand economy platforms like Uber, Lyft, Handy, and Postmates. This survey and other data sources have found that still only about 0.5 percent of all workers toil through on-demands platforms, but that the proportion is growing.12

Earnings Volatility since the Great Recession: Evidence from the SIPP

In the 1990s, economists began placing more emphasis on studying income variation. The seminal work in this literature is Gottschalk and Moffitt’s 1994 paper which found that the variance of earnings among prime-aged white males increased substantially between the early 1970s and late 1980s.13 By decomposing earnings variation into permanent and transitory changes—insofar as long-run inequality is concerned, it is the former that matters—they found that about half the measured increase in cross-sectional inequality was attributable to short-term fluctuations. Further, this pronounced transitory variance has accounted for between half (in the 1980s) and a third (by the 2000s) of the overall observed cross-sectional earnings inequality, underscoring that part of today’s historically high levels of inequality are attributable to workers facing greater short-term instability—a theme that if often underplayed.14 Numerous other scholars have confirmed and extended Gottschalk and Moffitt’s findings. Virtually all of these papers agree that transitory variance in male earnings increased in the 1970s and early 1980s, but there is a lack of consensus about post-1990 trends.15

Our present study seeks to add to the understanding of income instability in the post-Great Recession United States, and suggest policy responses. Who experiences income variability, to what extent, and why? What effects does instability have on well-being? To answer these questions, we use the 2008 Survey of Income Program (SIPP), which is a longitudinal survey of workers from 2008 to 2013. The SIPP is particularly well-suited to probe these issues, as it offers unmatched substantive and temporal detail, containing monthly data on a vast array of income, labor market, demographic, and household well-being measures for a large sample of some 50,000 household over a five-year stretch. The work most similar to the data analyzed in this report consists of a series of studies published by the Urban Institute.17 More importantly, large month-to-month variations that could be disguised by annual estimates of volatility are exposed in this data:

- Three out of five prime earners have at least one month in which their earnings drop by more than 50 percent.

- Half of all prime earners experience major drops in monthly income by more than 100 percent between months, as measured by the arc percent change.18

The results demonstrate that most primary earners face an earnings drop that will seriously test their ability to meet their basic expenses. In the best case, workers will be aware of volatility and be able to save during good months for bad months. But far too often, lower wage earners could face major stress paying bills and have little access to affordable credit to borrow in anticipation of better earnings periods.19

Importantly, job loss is not the only cause of these swings. Only 32 percent of those surveyed had a month when they were completely unemployed, and the number with major swings in income (more than 50 percent) is nearly double that. Clearly the variability of earnings has to do with more than just unemployment, but rather other life events, and wages, hours, and other aspects of earnings.

Measuring the Average Earnings Volatility of Primary Earners

The Gini coefficient—a measure of statistical dispersion frequently used to represent the income distribution of a nation’s residents—can also be used to assess the extent to which an individual’s own earnings are unequal from month-to-month. The Gini coefficient falls on a simple 0–1 scale, with 0 representing perfect equality, i.e., the same earnings every month, and 1 representing complete inequality, i.e., all income in a single month.

The average Gini coefficient of individuals is 0.31. This is far more equal than the Gini between workers—the Gini between U.S. households in 2014 was 0.48—but still quite high, given that we are talking about the month-to-month variability in an individual’s own earnings. To put it in tangible terms, a Gini this large in the context of average monthly earnings of $4,200 means that, for the average individual, the average difference in earnings between all pairs of months for which they were in the panel is on the order of $2,300–$2,600. This includes both positive and negative gains over this five-year period and represents a greater amount of volatility than is conventionally understood.

Which Workers Are Most Vulnerable to Economic Variability?

Table 1 displays the Gini coefficient for different demographic groups of workers, allowing us to compare variability between groups. Those groups shaded in red have earnings histories that are more variable, those that are in blue have earnings history that is more stable. A significance of means test was performed, those that are not statistically different from the mean are asterisked. Though these data are correlations, and are not causal, systematic differences among economic and demographic groups have important policy implications.

|

Table 1. Gini Coefficient of Earnings Volatility by Worker Characteristics |

|||

| Category | Gini Coefficient | Category | Gini Coefficient |

| All | 0.305 | ||

| Age | Industry | ||

| 16/24 | 0.517 | Agriculture & Nature | 0.410 |

| 25/34 | 0.298 | Mining* | 0.290 |

| 35/44 | 0.251 | Utilities | 0.198 |

| 45/54 | 0.252 | Construction | 0.340 |

| 55/64 | 0.296 | Manufacturing | 0.242 |

| 65/74 | 0.478 | Wholesale | 0.245 |

| 75+ | 0.623 | Retail | 0.321 |

| Education | Transportation* | 0.301 | |

| Less than HS | 0.380 | Information | 0.245 |

| High School | 0.342 | Finance | 0.221 |

| Some College* | 0.307 | Real Estate | 0.357 |

| Bachelors | 0.267 | Professional & Business | 0.258 |

| Advanced | 0.263 | Admin & Waste | 0.370 |

| Race | Education | 0.270 | |

| White | 0.300 | Health | 0.265 |

| Black | 0.351 | Social Assistance | 0.368 |

| Asian | 0.263 | Leisure & Hospitality | 0.369 |

| Other | 0.343 | Accommodation & Food | 0.370 |

| Hispanic* | 0.298 | Other Services* | 0.318 |

| Contingent | Private Households | 0.542 | |

| No | 0.254 | Public Admin | 0.225 |

| Yes | 0.433 | Armed Services | 0.211 |

| Income | |||

| 1st Income Quintile | 0.507 | Union | |

| 2nd Income Quintile | 0.327 | No | 0.315 |

| 3rd Income Quintile | 0.270 | Yes | 0.262 |

| 4th Income Quintile | 0.228 | ||

| 5th Income Quintile | 0.199 | ||

| Note: Asterisks(*) indicate no statistical significance at 5% level.

Source: Author’s Analysis of the Survey of Income and Program Participation. |

|||

Age

Earnings variability takes a U-shape with age, peaking among the youngest and oldest workers. While 16–24-year-olds have a Gini of 0.52, those ages 65–74 are not far off, at 0.48. Workers solidly in the middle of their careers—35–54 years—experience relatively little flux by comparison, with Ginis of 0.25. At the same time, recalling that our Gini is measuring the inequality in individuals’ own earnings over time, this is still a good bit of instability—on par with the levels of inequality we see across the population in the famously egalitarian Scandinavian countries.

Contingent Work Status

Workers in nontraditional work arrangements (self-employment, unpaid family work, temporary jobs, moonlighting and self-reported contingent work)—experience far greater flux than those who have more conventional jobs. The Gini coefficient for these workers (0.43) is nearly twice that of standard workers (0.25).

Industry of Employment

At the same time, as we might anticipate, workers in white collar (finance) and coveted blue collar sectors (manufacturing), have much more stable earnings than those in low-wage service sectors, including retail, food services, administrative, and waste services (janitors, etc.), leisure, and hospitality. Unions appear to play a protective role as unionized workers have lower than average variability as well.

Income Level

One of the most striking trends comes with household affluence, as income variability decreases monotonically with income quintile. Households in the bottom income quintile have far greater instability than the other four: a Gini of 0.51 which drops to 0.33 in the second quintile. Households at the top quintile have a Gini of just 0.20 on average. Those with the least to lose are most likely to lose it.

A regression model that combines labor market events and demographic factors is summarized in Table 2, and full detail is provided in Appendix 3. The key finding is that life events are most closely related to earnings volatility, more than demographic variables (sex, race) and household status (marriage).

In terms of demographics, a worker’s age seems to have the greatest impact on volatility followed by education, with better educated workers across different industries having less earning volatility. These factors have larger impacts than race and gender. In other words the racial differences in earnings stability appear to be because of the types of jobs and experiences held by different racial groups.

Labor market events appear to exert a strong influence on earnings volatility. With regard to the labor market, contingent workers experience the greatest earnings instability (+5 Gini points, even after accounting for the other variables in the model). Similarly, work hours and schedule play a significant role. Adding ten hours per week is associated with an earnings volatility reduction of 5 Gini points. Not surprisingly, a 10 percent increase in the amount of time a worker is laid off is associated with a 5.9 increase in the Gini coefficient of earnings.

| Table 2. Selected Significant Results, Ordinary Least Squares Regression of Impact of Demographic, Labor Market, and Life Event Factors on the Gini coefficient | |

| Coefficient | Full Sample, Weighted |

| Contingent Worker | 0.055 |

| Average Usual Hours Worked at All Jobs Per Week | -0.005 |

| Weekly Work Hours, All Jobs, Standard Deviation | 0.010 |

| Part-Time % – Share of <35-hour weeks | -0.148 |

| % of Months Work Hours Vary | 0.066 |

| % of Months with Layoff | 0.591 |

| % of Months Retired | 0.206 |

| % of Months Health/Disability Limitation | 0.190 |

| % of Months Family Obligation | 0.462 |

| % of Months School | 0.101 |

| HH Earners Chg. Indicator=1 | 0.014 |

| Marital Status Changed Indicator=1 | -0.024 |

| Constant | 0.569 |

| N | 26928 |

| r2 | 0.638 |

| Note:Author’s analysis of SIPP data. All coefficients are statistically significant at p<.05 level, with red numbers indicating higher earnings variation. | |

Impacts of Volatility on Well-being:

The upshot of the previous subsection is that earnings drops are common among workers. But does this variability in earnings affect household well-being? If the answer is no, then earnings volatility, whatever its magnitude, would be of limited concern to policymakers. But if variation in earnings appears to be systematically and meaningfully correlated with welfare, as indicated by other studies, then devising policies to address it is justifiably a priority.20

Results from a probit regression analysis are presented in Table 3 (below) which produces an estimate of the probability of failing to attain key dimensions of economic well-being, holding demographics and labor market characteristics (including work hours and their variability) constant.21

Results are presented by comparing the predicted probabilities of a primary earner at the 25th (“low volatility”) and 75th (“high volatility”) percentiles of earnings variability experiencing the hardship in question, holding all other variables at their means. For reference, the 25th percentile for the Gini is 0.075 and the 75th percentile is 0.473. The larger the gap in the probability of experiencing hardship between the two groups, the more predictive is earnings variability of hardship. All differences are significant at the 5 percent level unless otherwise noted.

Table 3 demonstrates the results from an analysis of all observations in the sample.22 The major finding is that earnings instability is strongly correlated with household hardship. The association is very strong for poverty and public benefit recipiency, moderately strong for inability to meet essential expenses and food insufficiency, and somewhat weak for housing and durables (consumer goods) insufficiency.

According to this model in the full sample, a primary earner in the 75th percentile of earnings variation has a probability of 0.47 of experiencing poverty at some point during the panel, while a primary earner in the 25th percentile of earnings variability has just a 17 percent chance of experiencing poverty-level income—a tremendous gap of 30 percentage points. Similarly, a high volatility worker has a 52 percent chance of receiving means-tested benefits, while her low volatility counterpart has a 38 percent chance. It’s worth emphasizing that these differences are attributable to earnings variation alone; this detailed model assumes these hypothetical workers are otherwise identical (specifically, “average” in all the demographic and labor market characteristics included in our detailed model). For an inability to meet essential expenses, the 75th percentile—25th percentile gap is 0.25 to 0.17; correspondingly, it is 0.33 to 0.28 for food insufficiency, 0.20 to 0.13 for unpaid housing, and 0.31 to 0.29 for durable goods insufficiency. A sub-analysis, not presented in detail, finds that the impact on poverty holds up even among the subset of workers that was employed throughout the entire period of the analysis. Volatility compromises well-being even among those who maintain employment over the long-term. Taken together, this suggests a causal relationship between earnings instability and household well-being.

| Table 3. Well-Being & Income Variation Regression Results: Predicted Probabilities of Experiencing Selected Hardships by Earning Volatility | |||

| Earnings Volatility | |||

| 25th Percentile | 75th Percentile | Difference: 75th – 25th | |

| Experience Poverty | 16.5% | 47.4% | 30.9% |

| Access Public Assistance | 37.6% | 51.5% | 13.9% |

| Able to Meet Essential Expenses | 16.7% | 24.7% | 8.0% |

| Food insecurity | 27.7% | 32.6% | 4.9% |

| Unpaid Housing | 13.2% | 20.2% | 7.0% |

| Durable Insecurity | 28.5% | 30.7% | 2.2% |

| Source: Author’s Analysis of the Survey of Income and Program Participation. | |||

Section II: Policy Solutions

A variety of policy proposals have been offered to address this future of unstable work. For example, President Obama’s 2017 budget proposal aggressively touts wage insurance. The target of this proposal is for workers who are laid off, qualify for unemployment insurance and receive a new job at less than their prior pay. The president’s wage insurance program would make up a part of the difference between the old salary and the new lower reemployment wage, through a government-funded wage subsidy.23 But this form of wage insurance would not apply to the growing numbers of workers for whom earnings volatility occurs even if they are not laid off.

To address scheduling uncertainly, policies advanced include:

- Reporting pay laws (in seven states and Washington, D.C.) that require employers to pay workers for a minimum number of hours if they are called in for a shift

- San Francisco’s Retail Workers Bill of Rights that requires various durations of notice of schedules and schedule changes, as well as “on-call pay” for cancelled shifts

- Right-to-request laws that shield employees from retaliation for requesting schedule changes

- The federal Schedules That Work Act, sponsored by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), which would call for some form of all the aforementioned protections for workers employed by employers with fifteen or more employees.24

On a broader macro level, a progressive tax code and work related tax credits like the earned income tax credit provide an automatic stabilizer of individual incomes, and improvements in the periodicity of these credits has been proposed as a response to earnings irregularities.25

This section focuses specifically on changes to unemployment insurance, and those aspects that could apply to workers who have volatile earnings even when they are not totally unemployed. First, we examine the obscure, poorly named, partial unemployment insurance (UI) benefits, which comes closer to what contingent worker advocates think of as wage insurance (at least for the portion of the workforce that is paid as employees and included in the unemployment insurance system). We also recommend new standards that would dramatically expand the program’s reach to part-time workers. Second, we describe another form of UI benefits paid to workers whose hours are reduced in lieu of layoff (work-sharing) and outline a proposal to expand work-sharing into a broader employer-driven program of schedule insurance for workers facing temporary cuts in hours. Our final pilot proposal would test whether the UI coverage could be extended to freelance workers who experience unexpected income drops with entrepreneurial assistance programs involved in assessing eligibility and assisting freelancers in stabilizing their businesses.26

Recommendation 1: Improving Americans’ Hidden Earnings Insurance—“Partial Unemployment Benefits”

Partial unemployment benefits apply to two types of earnings volatility. The first occurs when individuals are laid off and become totally unemployed (having zero earnings) and then pick up some part-time work at a different employer. This is sometimes referred to as part-total unemployment. Second, workers can file for partial unemployment benefits if their hours or earnings are reduced through no fault of their own. In other words, an individual can collect an unemployment payment without ever having been laid off—rather it serves as a form of earnings insurance. Eligibility for partial unemployment benefits is set by states and includes the following components:

- Eligibility: Individual earnings must be reduced to an amount that is less than a ceiling. This ceiling is expressed as a multiple of the weekly benefit amount that the worker would have received if they were laid off and totally unemployed. The average U.S. weekly benefit amount is $339 per week, and benefits are typically set at roughly 50 percent of a worker’s prior wage up to a limit set by that state law. As shown in Table 4, states on average set their cap at 116 percent of the full weekly benefit amount or just under $400 per week on average.

- Amount: A partial unemployment weekly amount is capped at the full weekly benefit amount. That amount is reduced dollar for dollar by the worker’s earnings—for every additional dollar a worker earns they get less in partial unemployment benefits. A certain amount of earnings is disregarded from the calculation—and this amount ensures that individuals would be better off working and collecting partial UI, rather than being fully laid off.

- Example: Idaho has a partial UI benefit formula that is among the more generous, and follows a typical pattern. It provides a ceiling of 150 percent of the worker’s weekly benefit amount and an earned income disregard of 50 percent of the weekly benefit amount. In Idaho, a worker earning $10 per hour and working forty hours per week would be eligible for $200 in UI benefits if the worker was laid off. Thus if that worker’s schedule was cut by 50 percent to twenty hours per week, the worker would be eligible for UI benefits because their new earnings of $200 was less than their $300 ceiling (150 percent of their potential full week’s UI benefit amount). The partial UI payment would be $100, after a disregard of 50 percent of the weekly benefit amount is applied.

$200 (WBA) – [ $200 (earnings) – $100 (disregard) ] = $100 in partial UI.

This can be thought of as 50 percent wage replacement. The worker lost $200 in earnings and was able to replace half of those earnings with a partial UI check.

Many workers do not qualify for a 50 percent replacement rate. First of all, state formulas vary enormously. The average weekly benefit only replaces 33.6 percent of the average worker’s earnings.27 Thus, in most states, even moderately paid workers would get less wage replacement from partial UI checks.

How Partial Unemployment Benefits Differ By State: An Analysis

The reach of partial unemployment benefits varies dramatically by state. In 2015, partial unemployment checks amounted to a high of 23.1 percent of all UI checks in Montana to a low of just 2.4 percent of checks in Louisiana.28 This metric, the best readily available, is the percent of all UI claims in the states that are paid as partial benefits.

The next section presents an analysis of how similarly situated individuals would fare in different states and how that appears related to how many partial unemployment claims are paid. Figure 2 compares the eligibility of two hypothetical workers for partial benefits—those earnings the state’s average weekly wage as of the fourth quarter of 2015 and those earning $10 per hour. It then compares whether individuals would be eligible for partial UI if their hours were cut by 25 percent, 40 percent, or 50 percent from a full forty hour per week schedule. (A detailed state-by-state analysis is included in the appendix.)

A few key observations from the analysis are summarized below:

- 25 percent reductions in wages are not enough to qualify for partial payments in most states. Only two states pay benefits to workers who are paid the average weekly wage and whose hours are cut 25 percent, and eight states pay benefits to workers who earn $10 per hour and whose schedules are cut by 25 percent.

- Low-wage workers are more likely to benefit from partial UI benefits than higher wage workers. A full-time worker paid $10 per hour who experiences a 40 percent drop in his/her hours would qualify in most states (twenty-six). A worker earning the average weekly wages and who lost 40 percent of their hours would only qualify for partial UI in ten states.

- Workers whose hours are cut in half are the most likely to qualify but eligibility is not universal. A worker paid the average weekly wage whose hours are cut in half only qualifies for partial UI in twenty states. If a full-time worker earning $10 per hour has his or her hours cut in half, the worker would qualify for partial UI in most states (thirty-seven).

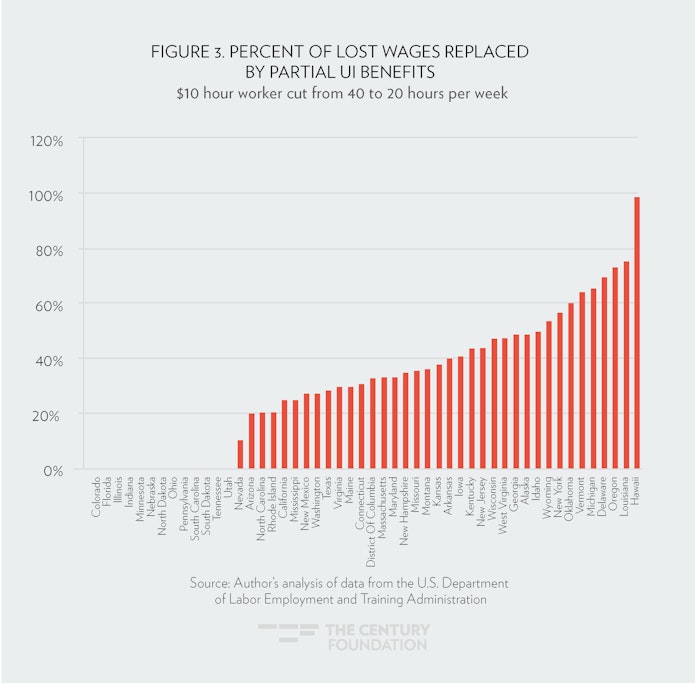

A further investigation of the differences in these state formulas is displayed in Table 4, using the single example of a $10 per hour wage worker whose benefits are cut by 50 percent.29 The table compares the ceiling of the formulas, using a single metric of the percentage of the full weekly benefit amount that these workers would qualify if they were fully unemployed. This mechanism is used by all but three states (Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin)—the minimum is 100 percent, and the maximum is 200 percent.30 This dimension of partial unemployment benefits will be described as accessibility.

Earned income disregard formulas vary in their construction but can be simplified as a dollar amount and used to compare how a similar worker would be treated in different states. For example, the hypothetical worker analyzed below living in Nevada would have an earned income disregard of $13 compared to a maximum of $150 in Hawaii. A worker would only be $13 better off working twenty hours a week in Nevada than being fully unemployed, as compared to $150 better off in Hawaii. This aspect of the benefit rule can be termed generosity.

| Table 4. Partial Benefits For a $10 per Hour Worker Cut from 40 Hours to 20 Hours Per Week, and Density of Partial UI Claims | |||||

| State | $ Partial UI Amount | % Earnings Replaced | Ceiling (Worker can earn no more than) | Earned Income Disregard | Partial Claims as a % of All Claims |

| Alabama | $0 | 0% | 100% | $66 | 6.3% |

| Alaska | $98 | 49% | 133% | $100 | 3.6% |

| Arizona | $40 | 20% | 100% | $32 | 3.4% |

| Arkansas | $80 | 40% | 140% | $80 | 13.0% |

| California31 | $50 | 25% | 125% | $50 | 8.1% |

| Colorado | $0 | 0% | 100% | $50 | 5.9% |

| Connecticut | $66 | 33% | 150% | $66 | 14.9% |

| Delaware | $139 | 70% | 150% | $113 | 7.4% |

| District Of Columbia32 | $66 | 33% | 125% | $66 | 6.7% |

| Florida | $0 | 0% | 100% | $58 | 4.0% |

| Georgia | $98 | 49% | 100% | $50 | 8.3% |

| Hawaii | $198 | 99% | 100% | $150 | 10.7% |

| Idaho | $100 | 50% | 150% | $100 | 12.3% |

| Illinois | $0 | 0% | 100% | $94 | 3.2% |

| Indiana | $0 | 0% | 100% | $38 | 2.9% |

| Iowa | $83 | 41% | 100% | $57 | 10.3% |

| Kansas | $76 | 38% | 100% | $55 | 8.1% |

| Kentucky | $88 | 44% | 125% | $40 | 6.1% |

| Louisiana | $151 | 76% | 100% | $104 | 2.4% |

| Maine | $61 | 31% | 100% | $25 | 5.4% |

| Maryland | $67 | 33% | 100% | $50 | 8.9% |

| Massachusetts | $67 | 33% | 133% | $67 | 6.7% |

| Michigan | $133 | 67% | 160% | NA | 8.8% |

| Minnesota | $0 | 0% | 100% | NA | 9.7% |

| Mississippi | $50 | 25% | 100% | $42 | 5.0% |

| Missouri | $72 | 36% | 125% | $64 | 8.0% |

| Montana | $73 | 36% | 200% | $75 | 23.1% |

| Nebraska | $0 | 0% | 100% | $50 | 6.0% |

| Nevada | $21 | 11% | 100% | $13 | 10.5% |

| New Hampshire | $70 | 35% | 130% | $62 | 10.0% |

| New Jersey | $88 | 44% | 120% | $48 | 12.0% |

| New Mexico | $54 | 27% | 100% | $42 | 3.1% |

| New York | $120 | 60% | NA | NA | 10.3% |

| North Carolina | $40 | 20% | NA | $40 | 4.8% |

| North Dakota | $0 | 0% | 100% | $120 | 3.1% |

| Ohio | $0 | 0% | 100% | $40 | 3.8% |

| Oklahoma | $128 | 64% | 100% | $102 | 3.9% |

| Oregon | $147 | 73% | 100% | $87 | 7.4% |

| Pennsylvania | $0 | 0% | 130% | $46 | 14.0% |

| Rhode Island | $40 | 20% | 100% | $40 | 7.1% |

| South Carolina | $0 | 0% | 100% | $50 | 8.1% |

| South Dakota | $0 | 0% | 100% | $44 | 6.2% |

| Tennessee | $0 | 0% | 100% | $50 | 4.4% |

| Texas | $60 | 30% | 125% | $52 | 8.5% |

| Utah | $0 | 0% | 100% | $60 | 6.6% |

| Vermont | $131 | 66% | 200% | $100 | 19.6% |

| Virginia | $60 | 30% | 100% | $52 | 6.6% |

| Washington | $55 | 28% | 133% | $55 | 10.3% |

| West Virginia | $95 | 48% | 100% | $62 | 6.6% |

| Wisconsin | $95 | 47% | FLAT | $87 | 18.0% |

| Wyoming | $108 | 54% | 100% | $100 | 6.5% |

| Average | $85 | 43% | 116% | $64 | 8.1% |

| Source: Author’s analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration. | |||||

A standard weekly unemployment insurance payment typically replaces half of a worker’s lost full-time earnings. A logical corollary would be that a partial unemployment check would replace half of a worker’s drop in earnings from part-time to full-time. Yet, only a handful of partial unemployment formulas do so. Figure 3 displays a replacement ratio for each of the states for the $10 per hour modeled in the analysis. Only ten states would replace half of the lost earnings of this type low-wage worker, and just two states (Oregon and Vermont) would afford the same wage replacement to a worker paid the average wage in each respective state. Fourteen states provide no partial benefits at all to even a $10 per worker whose schedule is cut in half. The shortcomings of partial benefits formulas are even worse for average wage workers, as most states provide zero wage replacement even to those workers who have their wages cut in half.

Next, we mapped the relationship between accessibility and generosity and how many workers collect partial benefits in each state. On this score, accessibility appears more important than generosity. Figure 4 aggregates the states into three groups: states with earning ceilings of 100 percent (thirty states), between 100 percent and 149 percent, and above 150 percent. The relationship is striking. In states with a replacement rate of 150 percent or above, a sizable 14.4 percent (nearly one in seven UI payments) are for partial checks compared to 8.9 percent in the middle group of states and 6.1 percent in the least accessible cohort.

The generosity of partial benefits and take up is not as strongly correlated. Figure 5 (below) groups the states in three groups based on their generosity—the top twelve states, the middle twenty-four states, and bottom twelve (three states—Michigan, New York, and Minnesota—use a method other than a disregard). There is little difference between the twelve most generous states and the next twenty-four average states, while the twelve least generous states are somewhat behind.

One other feature of more expansive state partial benefit formulas is worth noting. Ten states (Alaska, California, Connecticut, D.C., Kentucky, Montana, South Dakota, Vermont, and Washington) calculate the earned income disregard as a percent of wages, rather than a percent of the weekly benefit amount. As discussed above, workers who earn average wages qualify for the capped maximum weekly benefit amount. Thus an earned income disregard calculated as a percent of the weekly benefit amount will represent a smaller share of wages for these workers. In general (but not always), lower wage workers would be treated similarly by a weekly benefit amount formula as they would by a wage formula—for example an earned income disregard of 50 percent of wages or 50 percent of a Weekly Benefit Amount would be the same for a worker whose earnings were cut in half and did not qualify for the maximum weekly benefit amount. On average, states that calculate disregards as a percent of wages appear to provide partial UI to a greater share of workers: 11 percent of the claims in these states are for partial weeks compared to 7 percent in states using the weekly benefit amount formula.

Key Reforms to Realize the Potential of Partial Benefits

Details of partial benefits are left to the states, which can act on their own to make their partial benefits system a more meaningful response to income stability. These include both policy level changes that would have to be addressed by state legislatures and administrative improvements that would not.

- Ceiling: The most important reform to partial benefits would be for more states to adopt a standard of 150 percent of the average weekly benefit amount as the ceiling for eligibility. This standard, or a standard above it, has already been adopted by six states (Connecticut, Delaware, Idaho, Michigan, Montana, and Vermont).33

- Disregard: A disregard based on wages earned in part-time work has several advantages over the more common formula which sets the disregard as a percent of the weekly benefit amount. It is easier to understand for workers, who will know that exactly half of their wages will be deducted from the full weekly benefit amount they would have received if they were laid off. It levels the playing field for those workers whose earnings are high enough to be capped at the maximum weekly benefits. The advantage of an earned income disregard based on a percentage of weekly benefit amount is that it creates a symmetrical policy, with partial UI benefits going down by one dollar for each additional dollar earned up until the earned income disregard after which the partial UI check goes to zero. A standard earned income disregard of 50 percent of the weekly benefit amount would also be a strong minimum standard.

- Awareness: States don’t effectively let workers know that they could gain UI eligibility when their hours are cut. UI applications frequently couch such a situation under the broad umbrella of a “lack of work.” These workers would typically think of their own experience as a reduction in hours not a lack of work. The application should clearly indicate a separate box for a worker who has been reduced from full-time to part-time hours. While it might be impractical to require all employers to notify their employees when they are eligible for UI, states could easily develop a calculator with which workers could check their eligibility for partial UI.34

- Simplifying Administrative Requirements: UI claimants are generally required to certify their unemployment status each week after they have filed for UI. In many states, when workers want to file for partial UI benefits, they must use these weekly intervals to declare their earnings in that particular partial week. The state uses that information to determine their eligibility and the amount of benefits. Many workers are paid on a bi-weekly basis, and frequently confuse net and gross pay during the claims process. Thus, workers who provide the wrong wage amount while filing for partial UI are required by law to pay back any overpaid benefits. A better system would require states to allow for back-dating of UI claims for at least four weeks, and then allow for periodic reporting. Using this approach, a worker claiming UI would be allowed to submit pay documentation after the fact (e.g. two bi-weekly pay stubs covering four weeks) to the UI agency that would then calculate the amount of partial earnings. The agency should then allow the workers to wait another four weeks to submit two additional pay stubs to continue their eligibility. Adopting this approach would be a major incentive for workers facing reductions in hours to file for partial benefits without concern about overpayments.

- Federal standards: States would be most likely to enact a more generous formula if they were incentivized to adopt this recommended standard by federal law. Previous proposals have included stronger partial UI benefits as one of a set of federal minimum benefit standards.35 One straightforward way to incentivize this reform would be for the federal government to pay for 100 percent of partial benefits during recessionary times in those states that adopt this formula. This would have the advantage of providing additional incentives for those on federal extended benefits to work part-time. Like federal extended benefits, these additional partial UI payments would help to make up for the aggregate demand lost when there is a reduction in hours worked during a recession. Federal funding for partial weeks should be aligned with automatic triggers for federal extended benefits, as proposed by the Obama Administration.36 Such funding could mirror proposals to extend federal funding for work-sharing benefits for at least one year after the extended benefits program triggers on.37

Recommendation 2: Schedule Insurance

The reforms in partial unemployment benefits proposed in the preceding section would dramatically expand partial income replacement for unemployed workers who take on part-time work. However, they would not reach most workers who experience a loss of wages because their regular hours have been cut by 40 percent or less (see Figure 2, How many states provide partial UI benefits to workers whose hours are cut?). In this section, we propose an expansion of an existing unemployment insurance program known as work-sharing that differs from partial UI primarily because (a) it is triggered by an employer application and plan, and (b) it compensates workers for individual days of unemployment. Our view is that a relatively minor adjustment to the federal law governing work-sharing (also known as short-time compensation) offers an opportunity to expand the reach of the program to more businesses and industries that are subject to volatility in hours and wages.

Background: Work-Sharing

Unlike partial unemployment insurance, work-sharing is a program for which employers voluntarily apply when they are faced with a temporary decline in business. Instead of laying off a portion of the workforce to cut costs, an employer achieves equivalent savings by reducing the hours and wages of all employees or a particular group of workers. Workers with reduced hours and wages are eligible for pro-rated unemployment benefits to supplement their paychecks, while maintaining health insurance and other fringe benefits. At the same time, employers are able to temporarily reduce their payroll costs, retain skilled workers and avoid the future expense of recruiting, hiring and training new employees when business improves.

This is how it works: A business facing a 20 percent reduction in production might normally lay off one-fifth of its workforce. Faced with this situation, the employer instead submits a work-sharing plan to the state under which it would instead retain its total workforce on a four-day-a-week basis. This reduction from forty hours to thirty-two hours would cut production by the required 20 percent without reducing the number of employees. All affected employees would receive their wages based on four days of work and, in addition, receive a portion of unemployment benefits equal to 20 percent of the total weekly benefits that would have been payable had the employee been unemployed a full week. In this example, the full-time employee earning $800 per week, who is normally eligible for $400 a week in unemployment benefits, would receive $640 in wages for four days of work plus $80 in work-sharing benefits for the one day of unemployment (20 percent of the $400 weekly UI benefit).

Like regular unemployment benefits, work-sharing benefits only provide partial wage replacement. However, workers covered under an employer’s work-sharing plan are not subject to their state’s partial UI formulas, most of which would typically provide no benefits to an employee with a 20 percent or 40 percent reduction in hours and wages. In addition, employers who establish work-sharing plans must certify that health or retirement benefits will continue for covered employees working reduced hours as if they were working full-time. (For a comprehensive review of work-sharing program features, see Appendix B, “How Does a Typical Work-Sharing Program Operate?”)

Work-sharing was a little-known program in the United States until the Great Recession, when tens of thousands of companies were forced to consider layoffs for the first time. In the seventeen states that had active programs at the time, work-sharing claims activity increased ten-fold between 2007 and 2009 as employers looked for alternatives to layoffs that would help them retain skilled workers during a downturn they hoped would be temporary. Usage was particularly high in the manufacturing sector and soon other states began legislatively enacting work-sharing programs.38

The costs of work-sharing benefits are financed in the same way and under the same state laws as regular unemployment insurance benefits. An employer’s UI taxes are experience-rated based on how much unemployment activity is associated with that employer. Generally, costs and tax rate implications for one employee receiving a full week of UI benefits will be similar to five employees working four days a week receiving a 20 percent work-sharing benefit.

During the Great Recession and the prolonged period of high unemployment during the ensuing economic recovery, Congress and the Obama administration regularly engaged in political battle over the stimulative impact of additional weeks of federal unemployment benefits (Emergency Unemployment Compensation) as a response to the crisis of long-term unemployment. However, support for work-sharing during this period crossed political and ideological lines. As Kevin Hassett and Michael Strain at the American Enterprise Institute observed: “To the extent that work-sharing can keep some workers in jobs and out of long-term unemployment, it can increase potential output even after the recession passes…The damage caused by long-term unemployment is severe, inflicting high economic and human costs. Our current suite of policies is not up to the challenge….Other policies must be implemented and work-sharing should be at the top of the list.”39

In 2012, Congress enacted the Layoff Prevention Act, which established a new federal definition of short-time compensation and provided financial incentives to states with work-sharing programs that conform to the new federal standards.40 To date, twenty-eight states have enacted conforming work-sharing laws. Relying on data from the U.S. Department of Labor, the Center for Economic and Policy Research has estimated that work-sharing saved over 160,000 jobs in 2009 and over half a million jobs since 2008.41

Expanding Work-Sharing: Schedule Insurance for Employers Committing to Stable Hours Employment

The story of work-sharing during the Great Recession is instructive in that it provides an example of how some employers are willing to rely on a form of unemployment insurance to effectuate goals that are deemed critical to the operation (and sometimes survival) of the business. Work-sharing has enabled tens of thousands of employers to come out the other end of a business downturn healthy and sometimes even stronger. A recent study of work-sharing in four states (Kansas, Minnesota, Rhode Island, and Washington) found that employers most commonly cited the need to withstand loss of contracts and reduction of work during the recession as the driving reason for using the program.42 But not far behind were goals like maintaining employee morale, allowing employees to hold on to health insurance and other benefits, reducing hiring and training costs when business picks up again and avoiding bad press/negative reputation.43

Work-sharing has enabled tens of thousands of employers to come out the other end of a business downturn healthy and sometimes even stronger.

Work-sharing employers effectively adopt a business model that prioritizes the value of productive employees, encourages the retention of employees through the ebb and flow of business cycles and relies on the use of layoffs only as a last resort. And the program’s dramatic growth during the recession (even with minimal public awareness or marketing) demonstrates that many employers facing temporary economic challenges are willing to assume costs for UI benefits that are narrowly tailored to ameliorate the impact of unemployment in non-traditional ways.

Historically, manufacturing employers have represented the largest share of work-sharing program users nationally.44 However, there is evidence that promotion and marketing of work-sharing can impact the base and diversity of industries that utilize the program. Prior to the Great Recession, 90 percent of all work-sharing employers in Washington state were manufacturers, but from 2008–2013, that figure dropped to 27 percent.45 A recent examination of the industry mix of work-sharing employers in Washington showed substantial program usage in industries like construction, professional, scientific and technical services, retail trade, wholesale trade and health care and social assistance.46 This successful program expansion in Washington is largely attributable to extensive outreach to employers by staff and greater use of public media, and signals that the work-sharing program model has the potential to appeal to a wide swath of American businesses.

Two aspects of work-sharing stand out as different from traditional unemployment insurance. The first is the fact that employers apply for the program. While there are numerous examples of employers facilitating partial and temporary UI claim-filing by their employees, work-sharing is distinctive in that it is a UI benefit program that is initiated by and operates pursuant to a plan filed by an employer. And the employer-initiative feature is closely tied to the layoff aversion purpose of the program since it is the employer who certifies that hours are being reduced “in lieu of layoffs.”

The second non-traditional feature of work-sharing is the idea of providing a prorated UI benefit for a day of unemployment. Under virtually all state laws, full-time workers who experience one day of unemployment are not eligible for a UI benefit. Yet, under work-sharing, a state’s technical capacity to compensate a single day of unemployment enables employers to mitigate the harsh consequences of joblessness on a group of workers by spreading the pain/socializing the experience to the larger workforce.

As a method of partially compensating employees for lost days of work, the work-sharing approach (20 percent pro rata share of total UI weekly benefit) is more generous and carefully calibrated than the partial unemployment benefits model proposed in Recommendation #1. It operates on the premise that the employer is committed to providing a full-time work schedule that is being temporarily reduced to part-time until the employer can restore full-time hours.

While work-sharing is only available to employers who attest that schedule reductions are being imposed “in lieu of layoffs,” many employers reduce hours in response to other legitimate business circumstances (e.g. ebb and flow of business, seasonal factors, events impacting local economy) that would not necessarily otherwise trigger layoffs. We posit the idea that just as work-sharing helps employers avert layoffs by compensating full-time workers whose hours are being temporarily reduced by 20 or 40 percent, work-sharing could help high-road employers who commit to providing their workers stable schedules (32–40 hours weekly) by affording them the option to implement temporary targeted schedule reductions in which employees would be fairly compensated through the UI system.

Relying on work-sharing as a foundational template, a voluntary “schedule insurance” pilot program would be targeted toward employers who are committed to maintaining stable scheduling of at least thirty-two hours per week.47 After a federally-funded pilot period, a fully operational schedule insurance program would be funded through experience-rated UI taxes paid by participating employers. Like work-sharing, schedule insurance would differ from partial UI benefits in that it would pay benefits to workers who have an earnings loss that is too small to qualify for partial UI. Moreover, only employers could file for schedule insurance; workers could not file for schedule insurance on their own.

A major weakness in the economic recovery of the past seven years has been the dramatic growth in the percentage of Americans who are involuntarily working part-time. Reversing this trend will require innovative strategies aimed at moving these workers to full-time employment. A full-time job is not only the key to individual economic security; it is an engine of economic growth for American business. Being able to offer full-time employment makes a business more attractive to job seekers, more competitive in securing talent and better positioned to retain top performers. Schedule insurance is one policy option that could provide some employers with the flexibility to customize their use of the unemployment insurance system in a way that would support adoption of a business model built on full-time employment. Full-time employment in sectors where part-time schedules predominate may look different. For even full-time workers at these firms, certain weeks may provide fewer hours. Schedule insurance will provide extra income that can make these jobs a more reliable source of earnings and give employers the benefit of retaining experienced workers.

Proposed Schedule Insurance Pilot Program

- Expand work-sharing to offer a form of “schedule insurance” to employers who commit to provide full-time schedules of 32–40 hours per week.

- Expand base of employers. Before 2012, nonstandard workers did not generally participate in state work-sharing programs, and as a result, the vast majority of work-sharing plans cover employees who normally work forty hours per week (or full-time falls somewhere from 35–40 hours). However, the federal Layoff Prevention Act of 2012 does not include a provision that explicitly forecloses participation of part-time workers and thus provides an opening for program growth in industries where full-time schedules are typically less than forty hours per week.

- A pilot program expansion of work-sharing (to include schedule insurance) would be open to employers that are susceptible to reductions in business demand and the need to reduce hours, but are not necessarily making such reductions in lieu of layoffs. These employers would demonstrate their commitment to stable scheduling of at least thirty-two hours per week. In order to qualify for schedule insurance, an employer would need to document in its plan submission that it has a recent history of providing stable schedules to covered hourly workers. To qualify for schedule insurance, an employer would attest that covered workers have a full-time schedule of at least thirty-two hours per week and would document that in the year immediately prior to application, covered employees have worked at least thirty-two hours in at least thirty-nine weeks (or three-quarters of the weeks they have been employed, if employed less than a year).

- Participating employers would commit to stable scheduling for covered employees. The employer would submit a plan providing necessary information regarding the covered employees and specifying the number of hours that would constitute a full-time schedule. Employers would attest to make best efforts to provide full-time schedules every week to covered employees. (Like work-sharing, a schedule insurance plan would cover up to six months. Unlike work-sharing, plans could be renewed every six months so long as the employer is acting in compliance with the assurances made in the plan.)

- A prorated work-sharing benefit would be paid for weeks in which full-time schedules are not provided. For example, Employer A indicates that covered employees will work thirty-five hours per week. A covered employee scheduled for thirty-five hours of work has a seven-hour shift cancelled by the employer; that employee would qualify for a schedule insurance benefit. The employer would transmit a weekly claim at the end of the week to the state UI agency which would pay a schedule insurance benefit equal to 20 percent of what the individual would receive if s/he qualified for a full week of UI benefits. Covered employees would only be subject to schedule reductions ranging from 20–40 percent of their full-time schedules.

- States would have the option to limit schedule insurance benefits to employees who are UI-eligible and have worked for the participating employer for:

- At least six months (but may not set a minimum employment requirement greater than one year), and

- At least thirty-two hours or more in thirty-nine or more weeks in the year prior to application (or three-quarters of the weeks worked, if less than a year).

The fact that employees must have at least six months’ work history underscores that the schedule insurance benefit is to be made available only where the employer and employee have an established stable hours relationship. A year or more work history with the participating employer insures that the employer who submits the plan will absorb most or all of the UI costs through experience rating.

- Schedule insurance benefits would be limited to a maximum of eight weeks per covered employee during a six-month plan period. If a participating employer provides less than full-time hours to a covered employee for more than eight weeks during the plan period (or implements layoffs representing equivalent hours), no schedule insurance benefit would be paid beyond eight weeks and the employer would be removed from the program at the end of the plan period.

- Like regular work-sharing, schedule insurance would help retain skilled employees by guaranteeing a reliable income stream. However, unlike conventional work-sharing, the loss of skilled employees that the employer is insuring against is not the risk of layoffs but rather loss of staff who leave voluntarily when they do not get reliable hours. An employer’s incentive to use schedule insurance is the competitive advantage derived from guaranteeing a stable schedule of hours secured by a work-sharing benefit when there is a need to cut hours. An employer using schedule insurance may not be facing the certainty of layoffs but may want the flexibility to respond to short-term reductions in demand for products or services through single-week hours reductions while at the same time providing a stronger safety net for those workers adversely affected. The fact that the reduction in hours for workers receiving schedule insurance is not technically “in lieu of layoffs” represents the major distinction from the current statutory criteria for work-sharing (short-time compensation) under federal law. 48

- After a federally funded pilot period, benefits would be experience-rated so that the participating employer is generally carrying the cost of reducing hours in the form of increased UI tax rates in future years. In order to address concerns about the costs of benefits being partially absorbed by non-participating employers, states would have the option to assess a surcharge on certain employers (e.g. employers with negative unemployment experience, maximum-rated employers) who participate in the schedule insurance program. This approach, already endorsed by the U.S, Department of Labor for work-sharing, would address concerns about solvency and ineffective charging.49 Because of the prorating element, any covered employee who experiences a reduction in hours qualifies for a schedule insurance benefit. An employer that voluntarily applies for a plan of schedule insurance is assuming future UI costs that it would not normally incur under a standard partial UI formula. This election effectively represents the employer’s commitment to an employee’s value to the business, and any increase in future years’ UI tax rate is offset by immediate savings in wages.

- A state can disregard outside income if a covered employee attests that total hours worked with both employers will not exceed forty hours. This provision would encourage employer participation in the program since payments would not be affected by any wages that an employee earns from a second job (unless the combination of hours worked equates to a full-time forty-hour job). Not having to document other earnings makes scheduling insurance available for more workers, less complex and easier to administer for the employer and the state UI agency.

- Like work-sharing, the employer is submitting weekly schedule insurance claims on behalf of employees in which (a) the employer states how many hours the employee worked in a given week and (b) the employee attests (1) that they were available for their normal full-time hour schedule (the hours they worked plus the hours that were reduced below full-time), and (2) if the employee worked any hours for another employer in same week, total hours worked was not forty hours or more.

- Like work-sharing, if health and retirement benefits are provided, employers must certify that those benefits will not be reduced due to participation in the schedule insurance program.

- Like work-sharing under the federal Layoff Prevention Act of 2012, a schedule insurance pilot could be federally subsidized during a two-year pilot period. The federal subsidy would encourage employers who are uncertain about the program’s potential to participate on a trial basis. Ultimately, however, a permanent program would be financed by employers’ own UI taxes since experience rating would enable the participating employer to spread benefit costs out over three years of future UI contributions.

- During an economic downturn, a schedule insurance benefit could be federally subsidized when the state or national unemployment rate hits a recession-level trigger. A major unemployment insurance study recently recommended that work-sharing be fully federally-funded when state or national unemployment triggers signal an economic downturn.50 Just as it makes sense to encourage employers to avert layoffs by reducing hours when there is an economic downturn, it will make sense to encourage employers to stabilize schedules for as many workers as possible. This approach would also mirror the 100 percent federal subsidy of partial UI described in Recommendation #1. One key lesson of the recession is that there are a variety of ways to target federal UI spending that keep workers connected to their jobs at the beginning of the recession—as an alternative to all federal UI investments being directed to extended weeks of benefits for the long-term unemployed.

In summary, schedule insurance would represent a modest trial expansion of work-sharing that would effectively allow employers who commit to stable scheduling to provide workers a single-day UI benefit that is not generally available under state UI laws. After a federally subsidized two-year pilot period, the benefit would be paid for by the employer in the same way that regular unemployment insurance is funded. The program would be voluntary but limited to businesses that have an established commitment to stable scheduling and fair compensation to workers subject to occasional cuts in hours.

Recommendation 3: Extending UI benefits to Freelancers with Volatile Earnings

As indicated in the data section above, contingent workers have some of the greatest levels of earnings volatility. While some categories of contingent workers like those who work for temporary help agencies or work as temporary contract workers for hire might be eligible for UI, those who work as independent contractors are not eligible. Independent contractors are generally excluded from the unemployment insurance system by law. As described in a recent paper on the independent workforce, it is not easy to prevent the problem of moral hazard when including independent contractors in unemployment insurance.51 The problem of moral hazard is that individuals are less likely to guard against a potential risk if they have insurance. For wage and salary workers, the risk of moral hazard in the traditional UI program is limited because benefits are limited to workers who lose their job through no fault of their own. In theory, freelancers can choose when they work or not and it is more difficult to determine whether they have a drop in income because business has dried up or because they have turned down a gig. If moral hazard is too big a problem, freelancers could theoretically be better off without access to unemployment insurance than if they had it.

A large share of self-employed workers use freelance income to supplement regular income. However, states tend to treat freelance income in a more disadvantageous manner than regular employment. States will disqualify individuals laid off from a regular job from receiving UI benefits if they have even a sideline or temporary business, because they are considered to not be fully unemployed or be an “entrepreneur” instead of a worker. These disqualifications occur even if they don’t receive income from that business during the time period in question.52 They also could be disqualified if that income was so low (like a small family farm) that they would still be eligible if it was treated like regular partial income. States should solve this by equalizing treatment of partial income—only disqualifying individuals who have net income from a self-employed business. And states should not classify a recently laid off worker as an entrepreneur unless he has a successful business in their “regular trade.”

The exclusion of independent workers is a large hole in the UI safety net that should be filled if possible. Of particular concern is the estimated 19.1 million Americans whose income derives exclusively from freelancing, and don’t have a safety net to fall back on.53 One problem is that little is understood about how independent contractors would use unemployment insurance if they had access to it, and how their behavior might change. Would independent workers be able to contribute some of their earnings consistently to a UI fund over an extended time? What percentage of workers would claim benefits, and how would these compare to that of other types of workers and employers? If participation was voluntary, how bad would the problem of adverse selection be? How could states assess whether freelancers are available for and looking for work, and assist them to getting back to work? Could intermediary organizations that support entrepreneurs assist the state with assessing and assisting unemployed freelancers?

A pilot program would be one approach to assess possible ways to cover independent contractors with UI benefits. The U.S. Department of Labor has used pilot programs to develop many new approaches to UI benefits including job search assistance, worker profiling, self-employment assistance, and reemployment and eligibility assessments.54 Privately funded research could further investigate freelancers ability to contribute to UI and possible use of funds from the program.

California has long provided for optional coverage for unemployment insurance for self-employed individuals, and the law provides a useful basis for a larger pilot. To be part of the UI system, self-employed individuals have to produce a tax return showing an average profit of $4,600 in the prior year or attest to an average of $1,500 in quarterly profits for a year; show that the majority of their income comes from self-employment and that the self-employment serves as a “regular trade”; demonstrate that self-employment is not seasonal; and show that they do not expect to discontinue their regular business or trade in the next eight quarters.55

Below is an outline of a potential pilot program.

Program Eligibility

The overall structure would be to recruit a sample of self-employed individuals before they need help from UI to join the pilot program. They would need to agree to make contributions into a UI-like fund operated by the state for the pilot program, for at least four quarters before claiming UI benefits. UI benefits could be claimed at any point where the individual could show that their quarterly taxable self-employment earnings (as reported on their quarterly tax return) were at least 60 percent less than the average in their contributing year. This approach is recommended as self-employed individuals are more impacted by volatile earnings than strict “unemployment.” Thus, the pilot could test a UI approach that would address both employment and underemployment among freelancers.

Eligibility for the pilot program would be limited to experienced self-employed individuals who earn the majority of their income through self-employment, in a regular non-seasonal trade, and who can demonstrate at least a year of previous self-employment work on their annual or quarterly Schedule SE, with the $4,600 net profit threshold in California law a possible floor for eligibility.56 This would not include wage and salary workers who supplement earnings in standard employment with independent contractor work, and whose eligibility for UI is complicated by having both types of earnings. Nor would it include those who are misclassified as independent contractors. Rather this would test whether properly classified freelancers could gain access to UI benefits. To ensure that, those involved in the pilot program would screen participants for eligibility for traditional UI before being allowed the in the pilot.

In addition to having a drop in income, a freelancer would need to establish that their loss of income was due to a downturn in their self-employed business, not a lack of effort. Eligible reasons could include the unexpected loss of a customer or other unexpected declines in business activity. In the standard UI program, determining involuntary unemployment in complicated situations is accomplished through a questionnaire which is then verified by an employer. Having customers of freelancers provide verification for the reasons would prove administratively unfeasible. However, a detailed questionnaire legally attested to by the freelancer could achieve the same goal, especially if those administering the questionnaire could ask for substantiation. Substantiation could include statements and/or evidence that the individual had continued actively soliciting customers during the period for which they were claiming benefits.

A goal for the program should be that at least 50–100 individuals would collect UI in two different states, with pilot programs operating in a defined sub-state area like a city or a metropolitan area. If we assume that 50 percent of individuals would have a qualifying spell of low earnings, and that 50 percent would file for benefits, the pilot should recruit a sample of around 800 individuals per city (half in the control and half in the sample group).

Contributions and Benefits