Earlier this month, TCF fellow Thanassis Cambanis had a rare chance to visit Syria. In its fifth year of a grinding war, Syria has become something of a black box. It’s prohibitively dangerous to enter rebel-held areas, where foreigners and locals alike are routinely kidnapped or executed. The government of Bashar al-Assad, meanwhile, rarely hands out visas to Westerners.

During the ten days he was allowed inside Syria, Thanassis visited Homs, the emblematic and now destroyed seat of the popular resistance movement against Assad; the coastal cities where the government feels most secure; and Damascus, a capital city still rich in cultural and social life but deeply consumed by Syria’s fratricidal conflict.

What does a nation look like as it struggles to hold together under the unrelenting pressures of war? Through these snapshots of regular people and their neighborhoods, join Thanassis on his journey and share a glimpse of what everyday Syrians see.

Homs

Early in the uprising, Homs was known by anti-government activists as “The Capital of the Resistance.” Years of block-by-block urban fighting and a punishing siege destroyed the entire city center, leaving only an empty, apocalyptic no man’s land. In 2014, a few hundred people began haltingly to return to Old Homs. Now life is trickling back into a landscape of desolation, in fits and starts.

In the Old City of Homs, priests have reopened the Ghassanieh School, welcoming about two hundred students, most of them Christian. September 29 was the first day back since the end of siege in 2014.

An army recruitment poster at the entrance to Homs reads: “Our army means all of us.”

Urban gardening in Homs: one returning family has set up a chicken coop in the ruins of a shop in Hamidiyeh neighborhood.

The main square of Khaldiyeh, once a busy commercial intersection, is today completely abandoned but for checkpoints and sound of bombed metal creaking in the wind.

Blocks from the worst destruction, kids play soccer in the ruins of a school. Some Sunni families have returned to Hamidiyeh.

A man stops to examine the “wall of martyrs” in the pro-government Alawite neighborhood of Arman in Homs.

The first protests in Homs began in the iconic Clock Tower Square.

Famous Homs eggplants, apparently great for making makdous, for sale in Arman neighborhood.

A Christian youth group has painted murals to beautify Hamidiyeh neighborhood.

Renovations are underway at the historical Khalid ibn al Waleed mosque amidst destroyed Old Homs. The government wants to quickly reopen the city’s oldest historical church, Notre Dame de la Ceinture, as well as the mosque.

Panorama of the desolate remains of Khaldiyeh center, Old Homs.

Displaced people have crowded into the surviving new neighborhoods of Homs, like Ghouta. The owner of Troy Restaurant said he puts detergent in the water “so it smells nice.”

The Coast

The major coastal cities of Tartus and Latakia have been relatively protected from intense fighting, and they are home to a high concentration of government supporters, especially members of the Alawite minority. But the coast is ethnically diverse and hosts hundreds of thousands of Sunnis and others displaced by the fighting inland. The Assad clan hails from the mountain village of Qardaha, and the area’s families have contributed a disproportionate number of soldiers and militiamen to the government’s war effort.

A statue of Hafez al Assad greets drivers approaching Tartus from the north.

The Hashash family from Aleppo countryside has lived for four years in a displaced persons shelter in a converted office at the Social Affairs Ministry in Tartus.

Father Taamer says his Orthodox Christian congregation in Latakia has been shrinking steadily throughout the war. Most of the Christians who can afford the trip choose to emigrate from Syria.

Latakia fisherman dispel rumors that Israel unleashed sharks on the coast this summer. In the next picture, you can see the dogfish they caught.

“Don’t be alarmed, these are dogfish, not sharks,” the fisherman says of this recent catch. Dogfish are in fact a kind of shark.

Every day, visitors pay respects at the mausoleum in Qardaha where Hafez al-Assad, the father of the current president, is buried.

An entourage stops their conversation and looks up, following the jets booming overhead at the Hafez al Assad mausoleum in Qardaha.

An hour later we saw this jet (lower right in image) landing at Jableh. Maybe it was one of the planes we heard at Qardaha.

Mascot for the first annual art fair “Tartus, Mother of Martyrs,” at the mountain village of Naqib. Roughly 180 fighters have died just from the environs of Naqib, an area with a population of about 80,000 people.

The Old City, Damascus

The heart of historical Damascus is the Old City, a walled area that has been continuously inhabited for millennia and contains some of Syria’s most important antiquities and religious shrines. It is a bastion of commerce and coexistence, with a bristling market full of everyday items, spices, jewelry and Syria’s famous wood and textile crafts. Mortars regular strike the Old City along with the occasional car bomb, but life inside its walls can still feel remarkably timeless.

Antique dealers on Damascus Straight Street in the Old City haven’t seen tourists in years. The few who still bother to open their stores pass the time playing backgammon with each other.

Although the tourist economy is on hold, daily life is still bustling in the Old City.

One merchant in the Old City wears his politics on his sleeve. Outside his shop he displays rubber chickens labeled “Arab League” and rats labeled “Saudi” and “Isis.”

News may be boiling the week that Russia unleashed its military intervention, but there is still work to do on Straight Street.

Tourists or no, Nofara Cafe, beside the historic Ummayid Mosque, is full every night.

“I didn’t kill this turtle, it came from Asia!” says this silk merchant on Straight Street.

This Armenian genocide memorial was apparently erected this year for the centennial on Straight Street.

Husainiya

On the outskirts of Damascus, the fighting has been more intense. In the first two years of the war, the government almost lost control of the road to the airport and the Shia shrine of Saida Zainab. With extensive help from Iran and Hezbollah, the government regained control of the suburbs around the shrine. It took nearly two years, however, for the government to allow civilians to return to their homes in Husainiya, a neighborhood near the shrine.

The truck at the entrance to the Saida Zainab shrine on the outskirts of Damascus brews excellent espresso.

Palestinians have returned to their homes in this Damascus suburb years after the fighting there ended, but the government doesn’t entirely trust them and they are living with minimal services like water and electricity. Government soldiers still view fighting-age men like these with suspicion.

This extended family in Husainiya suburb of Damascus returned home last month, and are rebuilding their home without any official help.

Last month this lady learned to mix cement in order to help her husband repair the damage caused to their home in Husainiya by mortars and mines.

Damascus

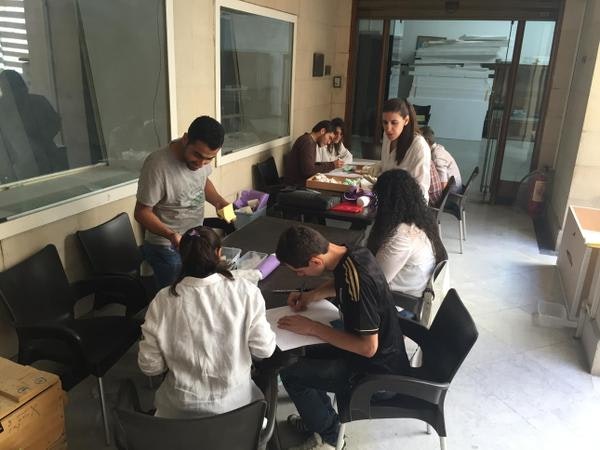

Team of archaeologists catalogue and package cuneiform tablets rescued from Deirezzor at the Damascus National Museum.

Syria antiquities chief Maamoun Abdulkarim reads reports from his informants of continuing destruction of antiquities across the country. Unless the international community intervenes to save the country’s best known sites, he said, “Nothing will remain in Palmyra after six more months of ISIS.”

A cuneiform tablet from the 2nd millennium BC rescued from Deirezzor. Archaeologists based in the shuttered Damascus Museum are processing the saved antiquities for safekeeping.

These funerary busts were dug up from Palmyra by the Islamic State, but officials in Lebanon confiscated them from traffickers. They’ve been returned to Syria where archaeologists will catalogue them and hide them in a bunker with other salvaged antiquities. Here they await processing in a gallery of the Damascus Museum.

This is one of the funerary busts from Palmyra rescued by officials. Archaeologists believe countless more have been destroyed or sold on the black market.

Conclusion

Since the war began, about half of all Syrians have been forced to flee their homes. About 8 million remain inside Syria, and another 4 million have left the country. On all sides of the conflict the infrastructure of daily life is strained or in shambles. Even under such horrific circumstances, those who remain in Syria try to preserve what they can of their routines—or in the case of many pictured here, to salvage something from the destruction. Sadly, there promises to be more.

To read more on Thanassis Cambanis’ trip to Syria check out his latest post “Inside Bashar Al Assad’s Syria.”