The aid effort that helps sustain millions in rebel-held northern Syria is under siege, threatened from all sides.

There seems to be no end in sight to a crackdown by Turkish authorities on international relief organizations providing cross-border assistance to Syria’s north from southern Turkey.1 Turkey’s ongoing campaign against international humanitarians now seems likely to shake more relief organizations out of Turkey, potentially interrupting the relief effort in Syria’s rebel-held northwest.

Yet humanitarians are also facing a more difficult operating environment across the border inside northwest Syria, where Hayat Tahrir al-Sham—the latest iteration of former Syrian al-Qaeda affiliate the Nusra Front—seems to have assumed a more overt, invasive role in relief provision and key aspects of civil life. Since the beginning of the year, humanitarians, donors, and others tell me, Tahrir al-Sham has stepped up its attempts to intervene in assistance in ways that have already complicated aid efforts. Now its declared intention to bring the northwest’s currency exchange and money transfer offices under its supervision is setting off alarm bells among humanitarians, who depend on informal “hawalah” transfers to operate inside Syria.

If Tahrir al-Sham takes overt hold of relief in the northwest, many humanitarians and donors already struggling to comply with capricious Turkish authorities could find themselves with little choice but to walk away.

If Tahrir al-Sham takes overt hold of relief in the northwest, many humanitarians and donors already struggling to comply with capricious Turkish authorities could find themselves with little choice but to walk away. The result would be disaster for northwest Syria’s relief regime—and for the hundreds of thousands of civilians who depend on it.

Interference by Syria’s various warring parties in humanitarian relief is not somehow new, or unique to the rebel northwest. The Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad has selectively denied humanitarian access to besieged opposition enclaves, undermining humanitarians’ impartiality and weaponizing their assistance in service of the regime’s ruthlessly effective siege-and-surrender strategy. Humanitarians also told me Kurdish-led authorities in Syria’s northeast have been pushing non-governmental organizations to register, which they were concerned might compromise humanitarians’ independence.

But dealing with Tahrir al-Sham—which is not itself a designated terrorist organization, but is covered by existing designations of the Nusra Front2—is especially fraught.

“We’re all bound by sanctions lists,” said an official with a Western donor government, who, like others interviewed for this article, requested anonymity to speak freely. “We can’t work with organizations linked to a listed entity.”3

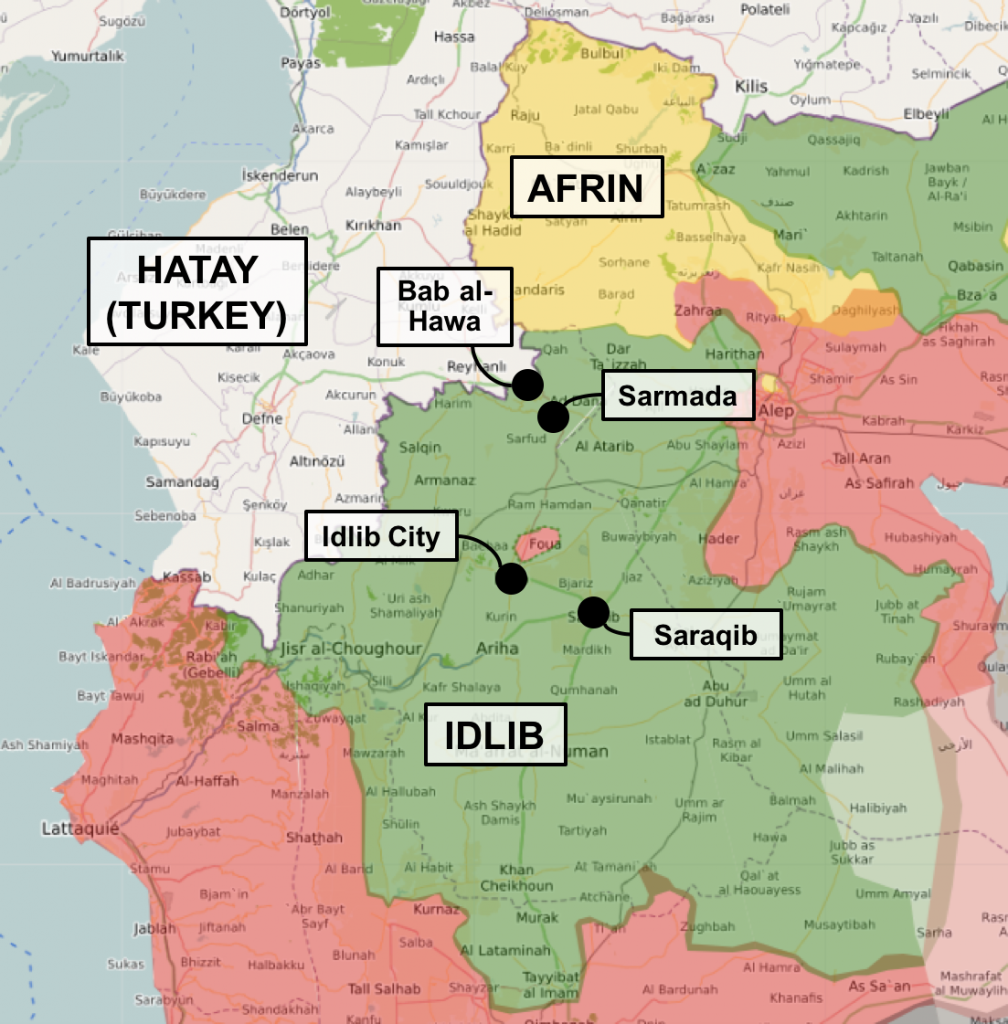

Humanitarians and stabilization contractors working from Turkey have mostly been excluded from Turkish-occupied eastern Aleppo province and Kurdish areas strung along Syria’s northern border. (They’ve mostly managed to serve the latter from Iraq.) The northern, Turkey-based section of the Syria aid effort is now almost entirely focused on Syria’s northwest, including Idlib province and sections of adjacent provinces.

In the Idlib-centered northwest, Tahrir al-Sham is the dominant armed actor. Yet the northwest also holds more than 2.3 million people, according to one estimate, mostly civilians.4 That includes more than 900,000 internally displaced people.

These people—particularly the displaced—are among Syria’s most needy.5 And to get to them, humanitarians and donors need to get through a newly intrusive Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.

Tahrir al-Sham Tries Financial Regulation

Tahrir al-Sham’s stated intention to oversee currency exchange and money transfer offices seems to be the most immediate cause for concern among humanitarians operating in the northwest.

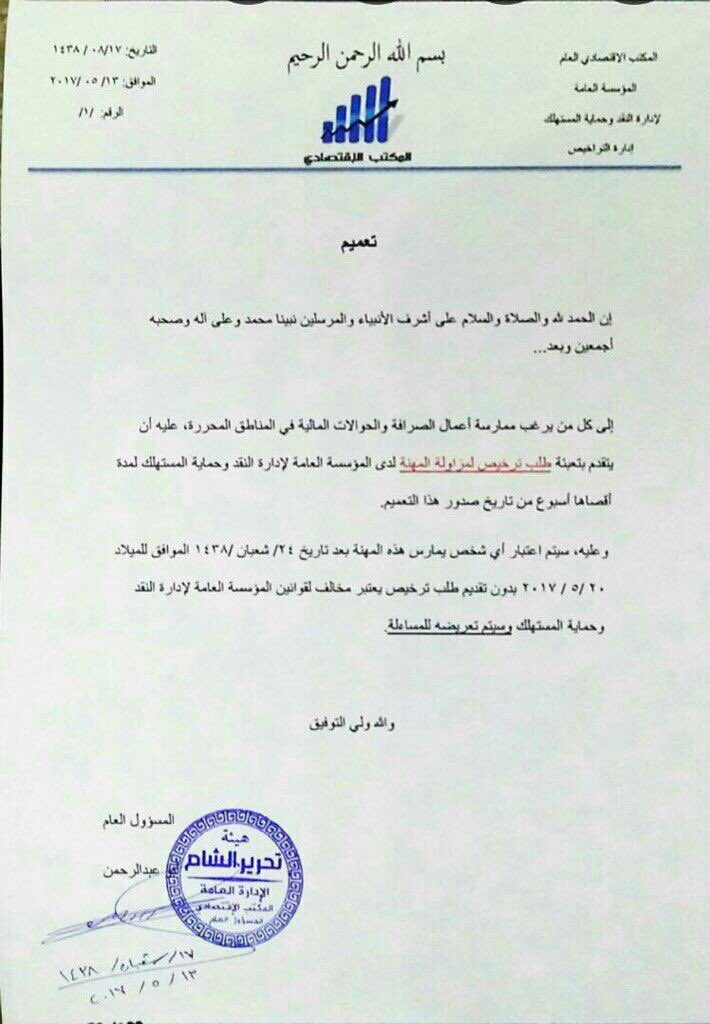

On May 11, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham’s “Economic Office” issued a statement announcing it would establish the “Public Institution for Currency Administration and Consumer Protection” to “administer and supervise the currency exchange market and financial transfers (hawalahs).”6

In a second statement issued May 13, the Economic Office gave all exchanges and hawalah offices in Syria’s northwest until May 20 to register with the new oversight body.7 Anyone who failed to do so, it said, would be considered “in violation of the laws of the Public Institution for Currency Administration and Consumer Protection and would be held accountable.”

Hawalahs are informal money transfers made outside regulated international banking networks and, to varying extents, with limited government oversight. Hawalah transfers are a necessity for humanitarians working in Syria, which has no functioning banking system.

Speaking to me over a messaging app, Tahrir al-Sham spokesman Emaddedin Mujahid confirmed the authenticity of both statements.

“A number of requests and complaints, from local residents and exchange owners, were sent to the Civil Administration for Services’ Economic Office [asking it] to carry out its responsibility to organize the work of these exchange offices,” Mujahid told me. “The Economic Office, in turn, organized a preparatory meeting with the biggest merchants working in the exchange sector. They presented their problems and the difficulties they faced, and it was proposed to them that we establish a unified system to which everyone can adhere.”

“[This system] would have benefits such as preventing the monopolization of the currency market by a few who benefit,” he continued, “getting the volume of currency flows under control, and confronting the economic war the regime uses to apply pressure when it manipulates the currency market.”8

There was no consensus among locals and interested humanitarians I interviewed about why Tahrir al-Sham was trying to do this, and why now. Some interviewees’ theories comported with Mujahid’s explanation: Tahrir al-Sham was reacting to wild fluctuations in the currency exchange market and a disparity in the exchange rate between Idlib and the neighboring Kurdish enclave of Afrin that speculators had exploited, as well as alleged collusion between financial offices and the Assad regime. Others told me they thought Tahrir al-Sham was simply trying to extract economic resources, potentially to brace itself for a rumored Turkish incursion into Idlib.

Mujahid gave an optimistic report on the regulation initiative’s progress so far. “This portfolio was studied by specialists, and the initial foundations were laid down,” he told me. “Given the necessity of establishing a sufficient database, we called on exchange offices to apply for registration in order to organize a working plan that agrees with and suits these merchants. The response was substantial—more than 500 offices applied for licenses.9

At time of publication, it was still unclear how successfully Tahrir al-Sham had corralled the north’s financial offices. Interviewees said they were taking Tahrir al-Sham’s stated intentions seriously, even if some were skeptical Tahrir al-Sham could impose itself on the other factional and economic interests involved.

To take hold of the financial system for the northwest, they told me, Tahrir al-Sham only really had to zero in on one north Idlib town: Sarmada.

Sarmada sits just inside the northwest’s only official border crossing with Turkey, Bab al-Hawa. The town, little-known before the war, has become the financial and commercial nerve center of northwestern Syria. Nearly all the northwest’s currency exchanges and money transfer offices are based in Sarmada.

Traditionally, the north’s factions have treated Sarmada as neutral or shared territory. Sarmada is the hub for the northwest’s traders, who are a power center in their own right—some interviewees called them “mafias”—and some of which have factional links or backing. But Tahrir al-Sham also has a key foothold in and around the town, including through its “Dar al-Qada” court and its “Islamic Police.” It’s through Tahrir al-Sham’s Sarmada checkpoint that the group has been able to exercise an effective veto on commercial and humanitarian traffic from Bab al-Hawa into the northwest. If Tahrir al-Sham were really determined to take Sarmada’s financial offices in hand, it’s not clear anyone could stop it.

These currency exchanges and hawalah offices never operated perfectly independently of local armed groups, interviewees told me, but Tahrir al-Sham’s new oversight initiative does seem like a qualitative—and disruptive—shift in that dynamic. Tahrir al-Sham hasn’t been subtle about it—it has broadcast the move publicly, which means it can’t be papered over or ignored.

Donors, humanitarians, and stabilization implementers all told me they’re tracking the issue closely. Cash payments currently represent only a small portion of relief programming in the northwest—as opposed to inaccessible, besieged areas, where they are critically important—and, at least for now, “truck-and-dump” relief can be shipped in through Bab al-Hawa. But relief organizations all use hawalahs to pay their staff and partners inside Syria, and if more INGOs are driven out of Turkey, then local, inside-Syria procurement using hawalah money could become a necessity.

Meddling with NGOs

Tahrir al-Sham’s intervention in the northwest’s financial sector may be the most alarming new development for humanitarians and donors, but it comes amid a seeming expansion of Tahrir al-Sham interference in local relief and civil society that is also raising red flags.

It is difficult to get a clear picture of circumstances inside the northwest, and Tahrir al-Sham’s involvement in relief in particular. Many relief workers inside the northwest and in neighboring Turkey are reluctant to discuss the role of Tahrir al-Sham, both because of concerns about physical safety of staff and local partners and because of the sensitive, potentially controversial aspects of how they’ve had to work around or with the Nusra Front and now Tahrir al-Sham.

More ad hoc, town-level interference with relief and other assistance by armed groups and other powerful local actors has long been a feature of relief work in north Syria, and one which humanitarians have had to continually resist. The involvement of the Nusra Front specifically ticked up in late 2014, interviewees told me, when it began pushing international and local NGOs to register via its Dar al-Qada court in Sarmada. At the time, some organizations complied and registered, securing a letter of permission to operate, while others resisted.

The pressure was enough to prompt relief NGOs to convene and agree on a shared set of principles for dealing with the Nusra Front, a document titled “Engagement with Parties to the Conflict to deliver Humanitarian Assistance in northern Syria,” drafted on December 9, 2014, and provided to me by a source in the humanitarian community.10 The document—which stressed core humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and operational independence—permitted humanitarians to request unhindered access to areas under the control of parties to Syria’s conflict, as well as to provide parties to the conflict with publicly available information on their organizations and information on planned humanitarian activities in those parties’ areas of control. The document said humanitarians would not, on the other hand, allow armed groups to access beneficiaries’ personal information, influence staff hiring or needs assessments, assign armed escorts to relief convoys or control storehouses, extract taxes or duties on aid deliveries, or take other invasive, compromising steps.

The Nusra Front’s 2014 registration push ultimately stalled, as did later registration appeals by rival armed factions like Ahrar al-Sham. Since then, armed group interference in relief has ticked up and down, both formally and in terms of informal guarantees of protection.

“In 2014, [the Nusra Front] insisted these organizations register for them to allow them to work,” one Idlib contact involved in relief and civil society told me. “But then, by the start of 2015, that failed, because organizations weren’t complying. Now every few days, they come up with some new idea.”11

Now, since the January announcement of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, the group may be making another more systematic attempt to intervene in relief provision. Interviewees described a seeming uptick in Tahrir al-Sham interference in relief over the last several months. Tahrir al-Sham’s brief confiscation of a flour shipment in Sarmada in March, en route from Bab al-Hawa south to the town of Saraqib, has been the most visible instance. But interviewees also said Tahrir al-Sham had made more low-key approaches to NGOs, including demanding beneficiary lists and attempting to extract a proportion of relief hauls, although some were unsure if this amounted to a new, deliberate project instead of ongoing, more standard interference.

“They’re trying to control these organizations, in one way or another,” said one Syrian humanitarian. “They’re asking for registration, specifying areas of operation, lists of beneficiaries, implementation for specific projects in specific areas. These kinds of things.”12

“We’re not quite sure whether it’s something which is the initiative of local commanders, or if it’s coming from the top,” one humanitarian told me.13 Information from inside the northwest is fragmentary, and internationals cautioned that they were relying on reports from local partners that might not be totally reliable.

If Tahrir al-Sham is attempting to envelop relief and civil society actors or to fold them into a Tahrir al-Sham-led institutional framework, that would sync with its mission and ethos. From the start, Tahrir al-Sham’s has made it clear it aims to unify and consolidate the entirety of the Syrian revolution.14

Central to this effort seems to be a Tahrir al-Sham “organizations office” or “associations office” that has reportedly been approaching NGOs. (Interviewees gave multiple, somewhat confused versions of the office’s name.)

Tahrir al-Sham spokesman Emaddedin Mujahid confirmed to me that the “Office for Supervision of Organizations and Associations” exists and is part of the larger “Civil Administration for Services.” The office is a “civilian supervisory body,” he told me, meant to “facilitate the work of humanitarian organizations and the delivery of support to those in need inside Syria; ensure relief and humanitarian work is brought to the highest levels of transparency and probity by limiting corruption and favoritism; and unify efforts to achieve the best desired results from humanitarian work.”

Mujahid denied that the Civil Administration for Services is related to any previous body. But that seems to be contradicted by the social media feeds of the Nusra Front’s municipal service body, the “Public Services Administration,”15 which, on May 22, were reflagged as the “Public Institution for Electricity.” The Public Institution for Electricity is—as its media branding indicates and as Mujahid confirmed to me—part of the Civil Administration for Services. The Civil Administration for Services thus appears to be either a renamed or a hybridized version of the Nusra Front’s previous service apparatus.

Mujahid denied that Tahrir al-Sham had asked any relief organizations to register or stopped any from working inside the northwest. “The issue doesn’t go beyond coordination and facilitation,” he told me. “There’s no control or set-asides or anything else along those lines. [We’ve been involved] because [Tahrir al-Sham] controls broad sections of the Syrian north, and because we’re present on the ground and we have a complete information bank about all the area’s needs.”

It may be possible for humanitarians to resist Tahrir al-Sham’s overtures again. So far, it is unclear how much of Tahrir al-Sham’s pressure is just bluster, and whether the group can follow through in sections of the northwest it doesn’t control outright. Some NGOs also operate under the implicit protection of rival factions like Ahrar al-Sham, and are likely to get a free pass.

“They’re tightening up more, but they just need to be handled with some toughness,” said a Syrian humanitarian.16

Blurred Lines

Tahrir al-Sham’s media is also blurring the line between Tahrir al-Sham and independent relief and civil society organizations in a way that is problematic for would-be foreign donors.

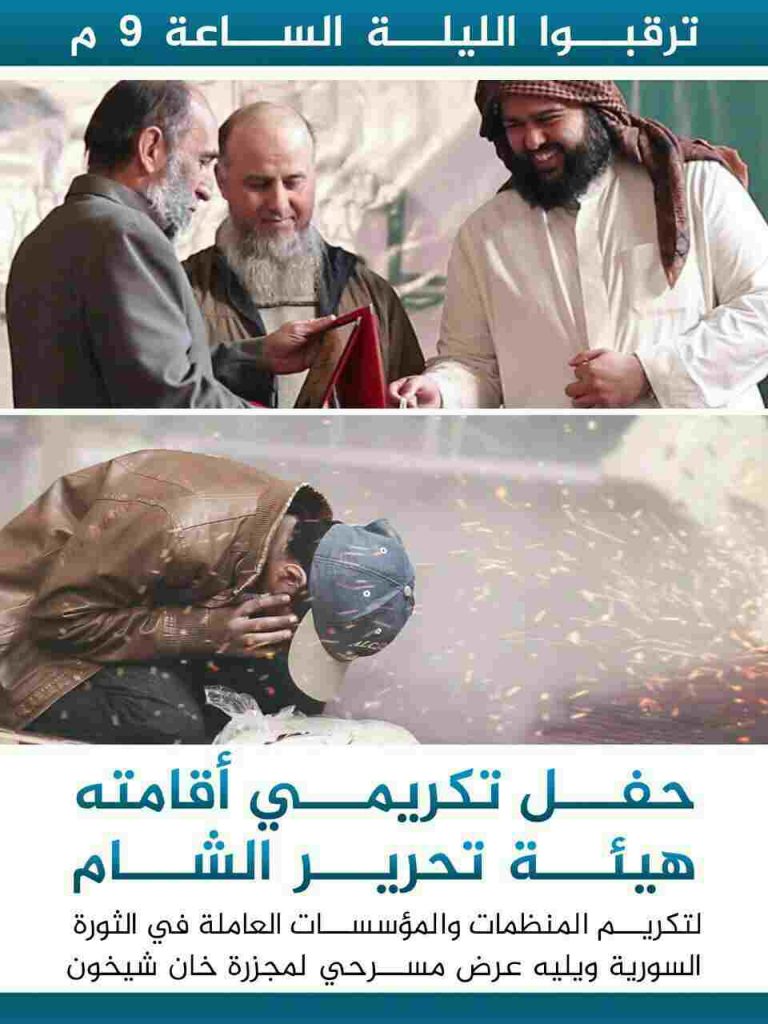

The most eyebrow-raising example to date was what one contact working on stabilization programming called Tahrir al-Sham’s “troll video.”17 In the video release, Tahrir al-Sham leader Hashem “Abu Jaber” al-Sheikh and leading religious official Abdullah al-Muheisini hand out awards and give thanks to representatives of various civil society bodies.18 These organizations, which the video terms “hidden soldiers,” include two relief organizations, “civil defense” emergency first responders, and several Idlib service directorates. Several recipients give speeches thanking and saluting Tahrir al-Sham, and then children stage a reenactment of the Assad regime’s April 4 chemical weapons attack on the Idlib town of Khan Sheikhoun.

On his channel on the messaging app Telegram, Muheisini excitedly hailed the video as “a leap forward for jihadist media,” which he said had been reproached for its narrow, militaristic focus.19

The awards video includes stock footage of Western-sponsored Syria Civil Defense (“White Helmets”) emergency first responders. Yet the actual “civil defense” representative at the ceremony came from Idlib city’s civil defense unit, which, per the Idlib responder’s red helmet, is not part of the Western-backed Syria Civil Defense organization.20

The Assad regime and its supporters—including Bashar al-Assad himself, when I interviewed him last year21—have consistently attempted to smear the White Helmets as the humanitarian arm of al-Qaeda.

One contact who works on Western stabilization programming said the video was “very damaging.”

“To me, it was exactly what the Syrian regime has been leveling at the opposition,” he told me. “It’s almost like Muheisini is too perfectly playing into that narrative. It tarnishes these organizations and feeds that story that has been promulgated on the regime and its supporters’ side that, ‘This is the opposition, these people you all say are good are really al-Qaeda.’”22

Stabilization assistance in Syria goes towards proto-governance and service bodies, as well as civil society organizations. It is more political and directed than humanitarian assistance, which is purely needs-based. Yet the two types of aid are also complementary—in rebel-held areas, for example, local councils developed and supported with stabilization assistance are key local partners in distributing humanitarian relief.

Tahrir al-Sham has also muddied the waters with photo releases from its Pride News Agency media organ, which has mixed scenes of Tahrir al-Sham fighters on the battlefield with photos of independent relief NGOs at work and, in one particularly innocuous instance, a match organized by the Syrian Volleyball Union in south Idlib.

Tahrir al-Sham may be attempting to demonstrate to its Syrian base how supportive it is of local civil society and how close it is to the northwest’s civilian community. In other important respects, it seems to be setting itself up as the champion and standard-bearer of the Syrian revolution, inserting non-jihadist revolutionary language into its statements and embracing other key elements of revolutionary symbolism.

Tahrir al-Sham may be attempting to demonstrate to its Syrian base how supportive it is of local civil society and how close it is to the northwest’s civilian community.

On May 15, Jenan Moussa, a reporter with Dubai-based Al Aan TV, released a mini-documentary titled “Secret Mission in Idlib” that relied heavily on hidden-camera footage to document the extent of jihadist control in the rebel-held northwest. Moussa’s portrayal of Idlib as a black-flag stronghold and a Syrian Kandahar provoked controversy and outrage in Syrian opposition circles.23

On Friday, May 26, Tahrir al-Sham apparently permitted a protest in Idlib city in which demonstrators raised both Islamic banners and the revolutionary tricolor.24 Nusra Front fighters had previously harassed and beaten activists who protested with the revolutionary flag;25 this time, it disseminated photos of the protest through its Pride News Agency. The episode recalled the group’s response to U.S. Special Envoy Michael Ratney’s March 11 statement clarifying that the United States considers Tahrir al-Sham an expansion of the Nusra Front, and thus a designated terror organization.26 At the time, Tahrir al-Sham came back with a statement framed almost entirely in ecumenical revolutionary language, seemingly deliberately, and shorn of jihadist rhetoric.27

In an excited May 26 post to his Telegram channel, Tahrir al-Sham religious official Muheisini hailed the Idlib protests. “What I saw was a message to those who say the revolution’s popular base is finished,” Muheisini wrote. “They raised the flag of the revolution—without a ‘secret mission’—and without the factions pursuing them, as Al Aan TV claims!”28 Muheisini is himself a Saudi jihadist who was individually designated a terrorist and sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury in November 2016.29

There is still some independent activism and civil society in the northwest that is—if not all directly opposed to Tahrir al-Sham—at least adjacent to and unrelated to it. Towns like Saraqib are seen as independent of jihadist control, and there has recently been encouraging headway organizing local council elections across the province that would give councils more popular weight and legitimacy.

Yet Tahrir al-Sham continues to burrow into the center of the northwest’s Syrian armed and civilian opposition. In doing so, it may frustrate and confuse its enemies’ attempts to isolate and target it. Yet it also risks rendering these other organizations, including local relief NGOs and civil society organizations, radioactive and off-limits to donor support—or at least to Western support, which is substantial.

Systemic Risk

The question now is whether Tahrir al-Sham’s interventions in relief and civil society will have a systemic impact on internationally sponsored assistance to Syria’s northwest, an aid and stabilization effort already shuddering under Turkey’s INGO crackdown and general donor fatigue.

“Donors are looking at this area,” one donor government official told me about Tahrir al-Sham’s interference in relief NGOs specifically. “They have red lines, some of which have been crossed. If they’re crossed repeatedly, they’ll need to look at it.”

“The only way we can come in as donors is if we can still ensure this assistance remains impartial, and not instrumentalized,” the official said.30

The official said he didn’t expect that donors would entirely cut off humanitarian assistance, but they might direct it to other areas not subject to the same armed-group interference. If those areas are few or small enough, though, the result will likely be an effective reduction in assistance overall. And even then, clearly delineating “Tahrir al-Sham” and “non-Tahrir al-Sham” areas inside the northwest is easier said than done.

“[People] can tell you where [Tahrir al-Sham] is stronger, sure,” a humanitarian told me. “But it’s present throughout [the northwest], and infused through the different structures they have.”31

Tahrir al-Sham’s new “organization” of the northwest’s currency exchanges and hawalah services seems most likely to cause problems for humanitarians and donors. Turkish official suspicion of hawalah payments has already helped spur Turkish authorities’ crackdown on relief INGOs, and Tahrir al-Sham’s move could bring more unwelcome scrutiny by the Turkish government. But as more humanitarians exit Turkey and attempt to maintain programming continuity in the northwest remotely from Lebanon and Jordan, hawalahs will become substantially more important. Tahrir al-Sham interference in hawalahs could make sanctions-compliant remote programming difficult or impossible.

“If in fact [Tahrir al-Sham] controls the entirety of the banking system of Idlib, yeah, that’s a big problem,” a stabilization sector contact told me.32

Continued assistance to the northwest may hinge on Tahrir al-Sham backing off its effort to control aid and the region’s economy for the sake of its civilian constituents—or, perhaps more cynically, on Tahrir al-Sham’s capacity for strategic thinking and its desire not to aggravate its base of support.

Local relief actors have their own contacts with Tahrir al-Sham, and United Nations humanitarians are permitted to engage all parties to a conflict—including a designated terrorist organization like Tahrir al-Sham—to discuss tactical issues related to humanitarian access and the delivery of assistance. With luck, Tahrir al-Sham can be made to understand that its encroachment on relief and civil society jeopardizes the donor-supported assistance that sustains the northwest’s civilian residents.

With luck, Tahrir al-Sham can be made to understand that its encroachment on relief and civil society jeopardizes the donor-supported assistance that sustains the northwest’s civilian residents.

“We’re hoping [Tahrir al-Sham] realize, as they did in the past, that they depend on aid to survive, and so these populations don’t revolt against them,” one donor official told me.33

“This subject is sensitive for people—relief, in particular,” said my Idlibi contact involved with relief and civil society. “If people get upset, they might stage protests at a time [Tahrir al-Sham] is trying to strengthen its popular base.”34

The millions of civilians in the northwest are already in a precarious situation, with hundreds of thousands dependent on a relief effort that’s endangered from without. The last thing they need is an interruption to needed assistance prompted, unbidden, by line-stepping jihadists inside the northwest itself.

Now continued assistance to Syria’s rebel northwest could depend on the judgment and restraint of jihadists on a path, as they see it, to glory and martyrdom—and on others’ ability to talk sense into people whose entire ethos is built on their defiant refusal to compromise.

Cover Image: Tahrir al-Sham graduates class of infantry commanders, source: Telegram

Notes

- Sam Heller, “Turkish Crackdown on Humanitarians Threatens Aid to Syrians,” The Century Foundation, May 3, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/turkish-crackdown-humanitarians-threatens-aid-syrians/.

- Aron Lund, “No, the United States Isn’t Dropping Syria’s Jihadis From Its Terror List,” The Century Foundation, May 18, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/no-united-states-isnt-dropping-syrias-jihadis-terror-list/.

- Donor government official, interview with the author, May 2017.

- Author’s estimate using the International Organization for Migration’s Needs and Population Monitoring Data for March 2017. For details on methodology, see Sam Heller (@abujamajem), Twitter, April 20, 2017, https://twitter.com/AbuJamajem/status/855009979375509508.

- For a sense of how many beneficiaries depend on cross-border relief from Turkey, see “Turkey | Syria: Humanitarian Dashboard – Cross Border Response Jan – Dec 2016 (Issued on 30 Mar 2017) (EN/AR),” UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, March 30, 2017, http://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/turkey-syria-humanitarian-dashboard-cross-border-response-jan-dec-2016.

- “Tahrir al-Sham Tuassis Dairah li-Muraqibat al-Sarrafah (Tahrir al-Sham Establishes Office to Supervise Currency Exchanges),” al-Dorar al-Shamiyyah, May 13, 2017, http://eldorar.com/node/111399.

- Sent to me by a contact in the stabilization sector, subsequently confirmed by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham spokesman Emaddedin Mujahid.

- Hayat Tahrir al-Sham spokesman Emaddedin Mujahid, interview with the author, Telegram, June 1, 2017.

- Ibid.

- Via a contact in the humanitarian community, May 2017.

- Idlib contact involved with relief and civil society, interview with the author, May 2017.

- Syrian humanitarian, interview with the author, May 2017.

- International humanitarian, interview with the author, May 2017.

- Sam Heller, “Syria’s Former al-Qaeda Affiliate Is Leading Rebels on a Suicide Mission,” The Century Foundation, March 1, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/syrias-former-al-qaeda-affiliate-leading-rebels-suicide-mission/.

- Sam Heller, “Keeping the Lights On in Rebel Idlib,” The Century Foundation, November 29, 2016, https://tcf.org/content/report/keeping-lights-rebel-idlib/.

- Syrian humanitarian, interview with the author, May 2017.

- Stabilization sector contact, interview with the author, May 2017.

- “Hayat Tahrir al-Sham Tukarrim al-Junoud al-Akhfiyya wa-Tuqim Ardan Masrahiyyan li-Majzarat al-Kimawi (Tahrir al-Sham Honors ‘Hidden Soldiers’ and Stages Theatrical Reenactment of Chemical Massacre,” “Hayat Tahrir al-Sham,” YouTube, May 14, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hR8LGeauoyY. The video was originally disseminated through Muheisini’s Telegram channel in Arabic, English, and Turkish.

- “Qanat D. Abdullah al-Muheisini (Dr. Abdullah al-Muheisini’s Channel)” channel, Telegram, May 14, 2017.

- A disclosure: In 2013 and 2014, I held a research position with a stabilization implementer that supported Syria Civil Defense.

- Sam Heller, “Assad Will Talk, But He Won’t Negotiation,” Foreign Policy, November 22, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/11/22/assad-will-talk-but-he-wont-negotiate/.

- Stabilization sector contact, interview with the author, May 2017.

- “Raddan ala Film Muhammah Sirriyyah ! fi Idlib (In Response to ‘Secret [!] Mission in Idlib’),” “Mousa Al Omar,” YouTube, May 17, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zs-Tp06pWBg; “Muhimmah Sirriyyah fi Idlib.. Keif Yuhaddid al-I’lam Hayyat 3 Milayyin Madani bi-Suwwar Murakkabah? – Huna Suriyya (‘Secret Mission in Idlib’… How the Media Threatens the Lives of Three Million Civilians with Composite Photos),” “Orient News,” YouTube, May 17, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IKJwDde3MjA.

- “Wikalat Ibaa al-Ikhbariyyah (Pride News Agency)” channel, Telegram, 26 May 2017.

- Osama Abu Zeid et al., “Nusra deflects blame for protest suppression; ‘mandate flag…sows division,’” Syria Direct, March 8, 2016, http://syriadirect.org/news/nusra-deflects-blame-for-protest-suppression-%E2%80%98mandate-flag%E2%80%A6sows-division%E2%80%99/.

- U.S. Embassy Syria (@USEmbassySyria), Twitter, March 11, 2017, https://twitter.com/USEmbassySyria/status/840540398602858499.

- Rami al-Dallati (@Rami_Dalati), Twitter, March 12, 2017, https://twitter.com/Rami_Dalati/status/840970248778088449.

- “Qanat D. Abdullah al-Muheisini (Dr. Abdullah al-Muheisini’s Channel)” channel, Telegram, May 26, 2017.

- “Treasury Designates Key Al-Nusrah Front Leaders,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, November 10, 2016, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl0605.aspx.

- Donor government official, interview with the author, May 2017.

- International humanitarian, interview with the author, May 2017.

- Stabilization sector contact, interview with the author, May 2017.

- Donor government official, interview with the author, May 2017.

- Idlib contact involved with relief and civil society, interview with the author, May 2017.