In the sixth year of its civil war, Syria is a shattered nation, broken into political, religious, and ethnic fragments. Most of the population remains under the control of President Bashar al-Assad, whose Russian- and Iranian-backed Ba‘ath Party government controls the major cities and the lion’s share of the country’s densely populated coastal and central-western areas.

Since the Russian military intervention that began in September 2015, Assad’s Syrian Arab Army and its Shia Islamist allies have seized ground from Sunni Arab rebel factions, many of which receive support from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, or the United States. The government now appears to be consolidating its hold on key areas.

Media attention has focused on the siege of rebel-held Eastern Aleppo, which began in summer 2016, and its reconquest by government forces in December 2016.1 The rebel enclave began to crumble in November 2016. Losing its stronghold in Aleppo would be a major strategic and symbolic defeat for the insurgency, and some supporters of the uprising may conclude that they have been defeated, though violence is unlikely to subside.

However, the Syrian government has also made major strides in another besieged enclave, closer to the capital. This area, known as the Eastern Ghouta, is larger than Eastern Aleppo both in terms of area and population—it may have around 450,000 inhabitants2—but it has gained very little media interest. One reason is that the political situation of the Eastern Ghouta is exceedingly complicated and difficult to parse. Despite a three-year army siege, ruthless shelling and airstrikes, and a sometimes very strict blockade on food and aid deliveries, discreet links have been maintained across the front lines. Even as they wage war on each other, certain progovernment and pro-opposition commanders remain connected through an informal wartime economy, muddling their political and military incentives and complicating any analysis of the situation.

The Eastern Ghouta is unique even in terms of its political players. Northern Syria is dominated by Islamist factions like Ahrar al-Sham, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Failaq al-Sham, and the al-Qaeda-linked Nusra Front (which renamed itself Fateh al-Sham in July 2016 and claims to have cut its ties with al-Qaeda). But these groups have only a limited presence in the Eastern Ghouta. There, instead, the insurgency has been led by factions indigenous to the area, including, at various times, a major Salafi group known as the Islam Army, the non-Salafi Islamists of Ajnad al-Sham, the self-declared Free Syrian Army faction Failaq al-Rahman, and local groups with opportunistic politics and uncertain ideology, such as Fajr al-Umma and the coalition known as the Umma Army.

In mid-2013, one of these factions began to overshadow all rivals: the Islam Army, a military-religious organization led by the Salafi firebrand Zahran Alloush, who would come to play a pivotal part in the Eastern Ghouta rebellion. By early 2015, Alloush had managed to pressure nearly all other local factions into joining military and judicial institutions under Islam Army dominance. The power of the Islam Army kept smaller factions in check and brought a modicum of stability to the enclave, allowing it to maintain a more or less united front against the Syrian government. Though he was resisted and reviled by critics who opposed his autocratic methods, Alloush began to appear as one of the insurgency’s few effective state-builders.

The efforts to establish a new political order under Alloush’s dominance make the Eastern Ghouta important to understand—and tragically relevant for the rest of Syria and, indeed, for other fragmented insurgencies. For over five years, the Syrian opposition has failed to produce any viable alternatives to the government it seeks to replace. Only two credible state-building projects have emerged in the territories abandoned by Assad’s regime: the Sunni-fundamentalist “caliphate” of the so-called Islamic State, and the Rojava region run by secular-leftist Kurdish groups. However, both have developed in opposition to the general thrust of the Sunni Arab insurgency and neither could hope to seize Damascus and rule Syria. While other Syrian opposition groups have created a variety of coalitions, military councils, and rival leaderships-in-exile, they have failed to develop effective ground-level governing structures that supersede factional divides and are able to impose themselves on the population. In the Eastern Ghouta, an exception to that rule seemed to be taking shape in 2014–15, led by the Islam Army.

But the balance of power that had enabled Alloush’s ascent eventually began to crumble, due to changes in the enclave’s political economy that weakened the Islam Army and provoked conflicts over smuggling revenues. Alloush’s death in December 2015 created a political vacuum that second- and third-tier factions sought to fill. As the Islam Army’s dominance faded, intra-rebel conflict resurfaced with devastating effect.

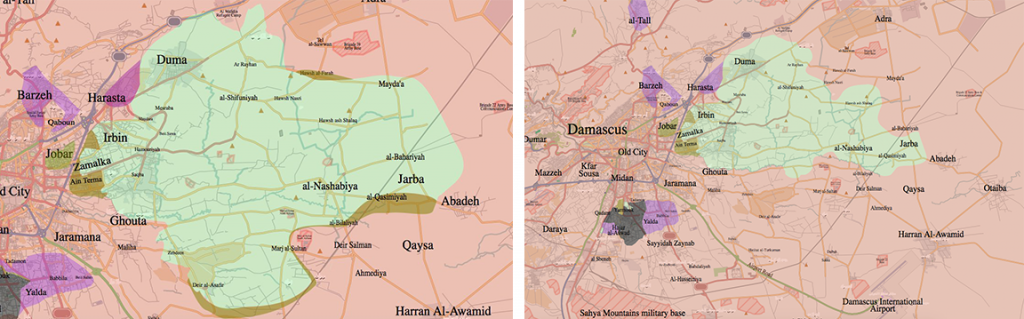

In April 2016, major infighting split the Eastern Ghouta enclave, putting a decisive end to the Eastern Ghouta’s experiment with rebel unity. It also seems to have hastened the end of the enclave itself. In the months since, the Syrian army has retaken about a third of the area, and it is now pushing to impose “ceasefire” deals that will effectively dismantle the last anti-government stronghold near the Syrian capital. If this succeeds, Bashar al-Assad will have dealt a crippling blow to the opposition.

Though the insurgency in the Eastern Ghouta has been the product of unique circumstances, the rise of its rebellion—and now likely also its fall—remains instructive for what it tells us about the development of factionalized insurgencies, how political order may be created from the bottom up, and what conditions facilitate state-building successes or presage their failure.

Methodology

This report attempts to chronicle the evolution of the Eastern Ghouta’s politics since 2011, with a focus on the relations between local armed factions. Much could undoubtedly be written about how the Syrian government and its supporters have reacted to events in the Eastern Ghouta, but such analysis falls outside the scope of this report except as it touches directly on events inside the enclave.

Unable to carry out research in the Eastern Ghouta or even meaningfully in Damascus to investigate these issues, I have instead relied on interviews with Syrians inside and outside the enclave, several of whom have to remain anonymous or are referred to by a pseudonym. Some interviews have been conducted in person, but most have taken place through Skype, phone, and email, or via Internet-based services such as WhatsApp, Telegram, Twitter, Viber, and Facebook.3

I have drawn a great deal of material from press statements by the relevant rebel factions and from Syrian government communications, as well as from online news sources and opposition forums in Arabic and English. Many rebel commanders maintain an active presence on Twitter and Facebook, and local activists have produced a wealth of commentary on social networking sites. Last but not least, coverage over the past few years by Syrian and international media, including from other Arab countries, has been an invaluable resource.

Nonetheless, the dearth of systematic research and the lack of reliable source material has been a severe problem. In many cases I have been forced to piece together key events and context by collecting and comparing scraps of limited, biased, or contradictory data. Despite my best efforts, this report is certain to contain errors of fact and interpretation, and I would like to stress that those failures are mine alone; no interviewee or other source should be held responsible for any of the descriptions, conclusions, or opinions expressed below.

The Eastern Ghouta

“…we came to Damascus; and we beheld it to be a city with trees and rivers and fruits and birds, as though it were a paradise…”

–The Thousand and One Nights

Since ancient times, Damascus has been known for the beauty of the Ghouta.4 A lush agricultural region into which old irrigation channels and pumps drove water from the river Barada and the wells of Damascus, it encircled the city on the west, south, and east, its expanse blocked only in the north by the bare, brown hump of Mount Qasioun. In the fourteenth century, Arab historian and geographer Ibn al-Wardi defined the Ghouta as “the region whose capital is Damascus,” describing it as

. . . full of water, flowering trees, and passing birds, with exquisite flowers, wrapped in branches and paradise-like greenery. For eighteen miles, it is nothing but gardens and castles, surrounded by high mountains in every direction, and from these mountains flows water, which forms into several rivers inside the Ghouta. It is the fairest place on earth, and the best of them.5

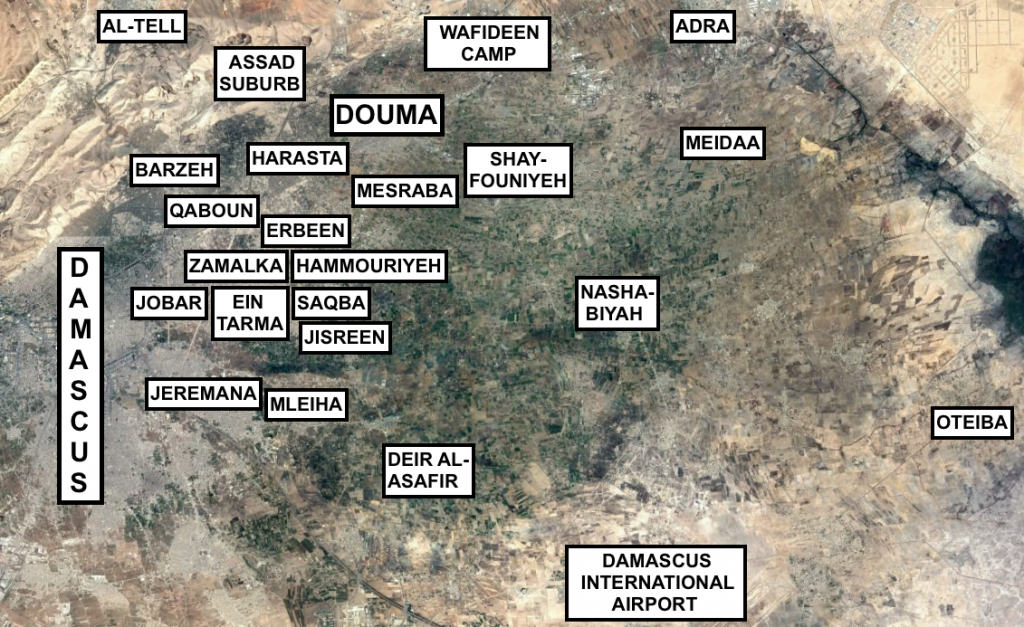

In towns and villages like Douma, Saqba, Harasta, and Jobar, the people of the Ghouta lived off the land, only a short distance from the bustle of the great city. Their olive and almond trees, orange groves, wheat fields, glittering canals, and morning mists would be the first sight of any traveler arriving to Damascus, a city known for its beauty—and that beauty was the Ghouta.

Following Syria’s independence from France in 1946, urbanization and technological changes began to transform the Damascene hinterland into a region of suburbs and satellite towns. Successive waves of refugees arrived, from Palestine in 1948–49 and from the Golan Heights in 1967. They were joined by poor Syrians seeking employment or shelter. Wheat fields were crisscrossed by roads and power lines, while factories, army compounds, and drab housing projects spread out of the city and into the countryside. The ancient oasis seemed destined to disappear.6

Douma, which had for hundreds of years been a small town of mosques and Islamic learning, grew into a city in its own right. Many villages were swallowed up by the capital, with, for example, Jobar—once a picturesque multireligious hamlet where Muslims and Jews tended their orchards—transformed into a series of mostly unremarkable city blocks on the eastern fringes of Damascus. Above, the air hummed with flights from the capital’s main airport, built in the southeast of the Ghouta in the 1970s. The transformation and immigration picked up speed as time passed, and statistics show a rapid expansion of new housing around Damascus from the 1990s onward.7 This outward expansion of the capital’s urban sprawl took place “without the slightest regard for environmental, aesthetic, or health concerns” and often without building permissions or planning. It ended up creating what researchers have termed a “belt of misery” around Damascus.8

Through these changes, much of the Ghouta’s overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim population clung to local tradition. Many were bitterly opposed to the authoritarian secularism of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party, which had seized power in 1963, and the Alawite military elite around the Assad family, which rose to power through then-defense minister Hafez al-Assad’s November 1970 coup d’état. In the 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century, labor migration and new information technologies allowed Gulf-backed Islamist movements to pick up on some of this discontent and penetrate the Syrian countryside.

Bashar al-Assad inherited power from his father in 2000. His first decade as president was marked by painful economic (as opposed to political) reforms, price shocks, and a severe drought, and more generally by the Ba’athist government’s turn away from its traditional base in the countryside in favor of the big cities. In a climate of mounting social crisis, discontent and desperation rose in rural regions, including the Ghouta. Throughout the first decade of the new century, slum areas around Damascus expanded rapidly as the capital and its satellite towns took in poor migrants, while spiraling living costs forced parts of the Damascene middle class to abandon the inner city for a congested daily commute. It was as if every driver of anti-regime resentment in the late Assad era had congregated on the outskirts of Damascus: political frustration, religious revanchism, rural dispossession, and downward social mobility.

When the Arab uprisings swept into Syria in March 2011, the comparatively affluent and carefully policed central neighborhoods of the capital hardly stirred—but the Ghouta rose fast and hard in an angry, desperate rebellion. “When the uprising first reached the capital in 2011, I noticed something odd as I followed the news,” recalled the British writer Matthew McNaught in a beautiful essay on the class dimension of the Syrian war as seen through the windows of the capital’s ubiquitous microbus taxis, the servees:

The first areas in Damascus that rose up against the regime sounded strangely familiar, although I had never visited them: Jobar, Douma, Barzeh, Ghouta, Qaboun, Harasta. It took a moment before it hit me. They were the names that I had seen every day on the roofs of passing microbuses. They were the destinations of the routes; places on the outer limits of the city’s sprawling suburbs. Some of them were lines that I had ridden regularly within the city. But I didn’t have any friends or students in these places. There were no famous restaurants or beauty spots there. I’d never had a reason to ride the servees to the end of the line.9

Suddenly, the end of the line had determined to make itself a new beginning.

The Creation of an Enclave

Five years into the Syrian crisis, the war for the capital seems to be coming to an end. Resistance in the Western Ghouta has been extinguished through the fall of Darayya in August 2016 and Khan al-Shih in November. Rebel areas south of the capital have gone the same way, with the neighborhoods of Yarmouk and al-Hajar al-Aswad isolated and primed for surrender.

Only east of Damascus does the rebellion still flare violently, a lingering threat to Bashar al-Assad’s control over the Syrian capital.

In the Eastern Ghouta, government control began to fray almost immediately in March 2011, as the government cracked down on any public expression of protest. Hundreds of demonstrators were killed or wounded by security forces in the first months of the crisis. Early attempts by commanders in the Republican Guard to negotiate with notables from Douma, the largest city in the Eastern Ghouta, were overtaken by violence or, in some cases, blocked by hardliners in the intelligence services.10

Hardliners also surfaced on the opposition side. Masked men put up roadblocks and Kalashnikov-toting locals were seen in Douma soon after the first crackdowns, but there was no semblance of an organized armed rebellion. It took until summer 2011 before a structured and politicized insurgency began to develop. Some of the armed groups were led by local Islamists, including men recently amnestied by the government, but others were made up of military defectors or local street toughs with no evident ideology. Many were inspired by Colonel Riad al-Asaad’s July 29 declaration in Turkey of the establishment of the Free Syrian Army. While the Free Syrian Army was always more of a brand name than an effective organization, Asaad’s announcement accelerated the formation of armed groups across Syria by providing a symbolic focal point and a template for armed resistance, and by shifting the wider opposition discourse in favor of a military struggle.

By the end of 2011, the opposition had seized entire neighborhoods in Douma and eastern Damascus and was disrupting day-to-day government control over perhaps a million citizens. The army sent tanks into the east of the capital in January 2012, briefly wresting Saqba, Erbeen, Hammouriyeh, and other suburbs from the opposition in what had now evolved into “urban war.”11 But with large quantities of weapons being smuggled into the Ghouta area from Turkey, the rebellion kept growing and the army could not sustain its gains. In late 2012, the last troops fled Douma.

By early 2013, the opposition controlled an area in the Eastern Ghouta that stretched from the Damascus suburbs in the west to the desert town of Oteiba in the east, and from Douma in the north to the outskirts of the Damascus International Airport in the south. Within these lines, Bashar al-Assad’s government had ceased to exist.

At this point, Assad gave up his attempts to roll back the rebels and instead sought to contain them, backed by Shia Islamist militias such as Lebanese Hezbollah and various Iraqi groups. The pro-Assad coalition launched a reinvigorated offensive to shore up government defenses, and then sent armored columns to cut off the flow of arms from Turkey through the Syrian desert.

In April 2013, the government retook Oteiba and began to choke off access to the rebel territory it had surrounded. The opposition launched a counteroffensive in May, backed by nearly all the rebel groups that now operated in the area: the Islam Brigade, the Douma Martyrs Brigade, the Martyrs of Islam, the Nusra Front, Ahrar al-Sham, and many others.12 “The battle of Oteiba was a tipping point between success and disaster,” said a member of a rebel faction in the Damascus region, who noted the town’s key role as a link between the Eastern Ghouta region and the smuggling routes that ran through the desert and the Qalamoun Mountains. “It was not the only such place,” he said, “but it was the last one.”13

By mid-June, it was clear that the army could not be dislodged: the Eastern Ghouta had turned into an island of opposition control, an isolated territory under siege. Having failed to break the siege in the east, the insurgent forces were drawn deep into the battle for the Damascus suburbs. The fighting was brutal and the rebels reported a growing number of small, tactical nerve gas attacks, culminating in a gruesome massacre of civilians on August 21, 2013. As the siege hardened, the horizons of the Eastern Ghouta shrank, and its defenders were increasingly preoccupied by how to defend, organize, and rule the enclave in which they had been trapped.

A Key Leader: Zahran Alloush

As in all of Syria, the opposition in the Eastern Ghouta has suffered from its fragmentation. Over the past five years, dozens of local factions have spawned and split in the areas east of Damascus, slowly coalescing to create a handful of larger umbrella movements.

The most important of the groups to emerge in the Eastern Ghouta was the Islam Army (Jaysh al-Islam), which rose to dominance from 2013 onwards under the leadership of Mohammed Zahran Alloush, also known as Abu Abdullah. Over the next two years, he would establish himself as the central figure in the enclave’s factional landscape and demonstrate the pivotal role that a single individual can play in the midst of political upheaval. It is worth looking at his background in some detail.

Zahran Alloush was born in Douma in 1971. His father, Abdullah Alloush (b. 1937), was an Islamic scholar who espoused the ultra-orthodox Salafi school of Sunni Islam, as understood by the religious establishment in Saudi Arabia. This brand of Salafism stresses personal piety and doctrinal purity. But although it, too, seeks a theocracy based on the strict application of sharia law and is hostile to Shia Muslims and other non-Sunni minorities, it differs in important respects from the Salafi-jihadi teachings popular in al-Qaeda and likeminded movements. “It is a traditional type of Salafism, what we call salafiyya ‘ilmiyya [scholarly Salafism],” said Abdulrahman Alhaj, a Turkey-based specialist in Syrian Islamism and a former minister in the opposition’s exile government. “They don’t have a global agenda. Their agenda is almost purely religious and national. Jihad is not the aim, the aim is to correct people’s beliefs.”14

Such views found fertile soil in Douma, a famously conservative city sometimes known as the City of Minarets. It is one of very few places in Syria and the wider Levant to be dominated by the Hanbali school of Sunni Islam, which predominates in Saudi Arabia, and this facilitated the spread of Salafi teachings.

Abdullah Alloush had been one of the leading exponents of modern Salafism in the Eastern Ghouta. In the early 1980s, he became the imam of the Tawhid Mosque in southern Douma, and in 1985 he was permitted to open a Douma branch of the Assad Institute for Memorizing the Quran. At this time, the Syrian government focused its attention on the rival Islamists of the Muslim Brotherhood, which had been involved in an armed uprising in 1979–82, but the Alloush family later came into conflict with both the authorities and rival clerics in Douma. Abdullah Alloush was never arrested, but claims to have been repeatedly called in for questioning and suffered police harassment, and he eventually immigrated to Saudi Arabia in the mid-1990s.15 His son Zahran reportedly had his first run-in with the security apparatus as a teenager in 1987.16

Zahran Alloush began to study Islam as a child, first under his father and then under other Syrian religious scholars. He continued his religious studies at Damascus University and later enrolled at the University of Medina in Saudi Arabia, studying under Salafi religious luminaries such as Ibn Baz (1910–99), Ibn Othaimin (1925–2001), and Mohammed Nasreddine al-Albani (1914–99). Back in Syria, Alloush capped his education with a master’s degree at the Sharia Faculty in Baramkeh in central Damascus. He then went into private business, with some sources saying he ran a shop or company selling honey, while others insist that he founded a construction consultancy. Whatever the nature of his work, his real vocation seems to have been secret Salafi missionary activity. During that period, he was deeply involved in running study circles and distributing banned religious literature, and possibly also in organizing support for the Iraqi insurgency, though all sources seem to agree he never carried arms either in Iraq or in Syria.

In 2009, the Assad government arrested Zahran Alloush as part of a broader crackdown on Sunni religious activism and Islamist militancy. He ended up in the Sednaya Prison alongside hundreds of other Islamist prisoners, many of whom had volunteered with al-Qaeda in the Iraq War. Rubbing shoulders with these men, he reportedly emerged as a respected leader in the prison. Alloush was still in jail when the Syrian uprising began in March 2011, but he was released in a presidential amnesty on June 22, 2011. He immediately joined the budding insurgency in his hometown, Douma.17

2011–12: The Early Insurgency

In summer 2011, the Eastern Ghouta was a hotbed of political ferment. Several small groups had taken up arms against the government, most of them using the Free Syrian Army moniker.

After his release from prison, Zahran Alloush and his Salafi allies initially worked with the Obeida Ibn Jarrah Battalion of the Free Syrian Army, which was reportedly the first armed group in the Eastern Ghouta.18 Formally established under that name in or around August 2011, it was led by “Abu Mohammed,” a retired Kurdish lieutenant-colonel from the Rukneddine neighborhood of Damascus, and does not seem to have been an explicitly Islamist group.19 However, as the Damascus insurgency grew in autumn 2011 and new armed groups mushroomed across the region, the Obeida Ibn Jarrah Battalion fell apart.

By September 2011 at the latest, Zahran Alloush had gathered his followers into a new faction under his own leadership. Known as the Islam Company (Sariyat al-Islam), it reportedly started with a small core of only fourteen members, several of them religious students or scholars like Alloush. It then grew quickly by drawing on old networks connected to the Tawhid Mosque and other Salafi institutions in Douma, an environment that apart from the Alloushes also included members of the Boueidini, Delwan, and Sheikh Bzeineh families.20 For example, the Salafi preacher Sa‘id Delwan (a.k.a. Abu Nouman, 1948–) had led Friday prayers in the Tawhid Mosque in the 1980s, and he now lent his support to Alloush’s militia.21

Although others contributed to the founding of the Islam Company, Zahran Alloush was undisputedly its central figure. He seems to have had a knack for organization, combined with an authoritarian, centralizing streak that would soon make its mark on the Eastern Ghouta insurgency. The Islam Company appears to have borrowed its organizational model from the Iraq War jihadi factions in which many Syrian Islamists had fought. It bestowed complete executive power on Zahran Alloush, unchecked except by the constraints of sharia, and he would take advice but not orders from a shura council (or “consultative council”) led by religious scholars and other important figures.

The Islam Company’s first documented attack seems to have been a nighttime raid against a checkpoint in Mesraba, near Douma, in September or October 2011.22 But the group’s distinguishing feature was not, at this early stage, its military capacity. Rather, the Islam Company stood out among the rebels in Douma for its overtly religious and missionary character.

Much of the early insurgency in the city was led by local toughs, who were sometimes members of Douma’s old families and in some cases linked to organized crime. Though they wrapped themselves in Islamic rhetoric when appearing as rebel leaders, many were not particularly religious or ideological. One Syrian researcher refers to them as qabadayat, an old term for the opportunistic neighborhood strongmen who ruled the streets and played politics in Ottoman and French mandate days.23 Some such networks would later coalesce into Free Syrian Army groups like the Douma Martyrs’ Brigade or the Douma Shields Brigade, early incarnations of which played a major role in driving government forces out of Douma city in 2012 under the leadership of local commanders Abu Subhi Taha (real name Ahmed Rateb) and Abu Ali Khibbiyeh (real name Majed Khibbiyeh).

According to one of Zahran Alloush’s early associates, Essam Boueidani, the Islam Company approached these factions as an ally and “taught them how to do the ablution and establish the prayer. Most of them didn’t pray. They were kind people but they didn’t pray.”24

The Islam Company’s religious identity was an important source of attraction as it sought to gather new recruits. Though Alloush’s fundamentalist rhetoric and Saudi connections caused alarm among secularists and some anti-Salafi Islamic scholars, they were not strong or united enough to put up effective resistance. More importantly, his views were not unpopular with the much larger conservative Sunni population in Douma. Indeed, the Islam Company’s ability to portray itself as a religiously observant and uncorrupted force against the Assad government drew recruits away from the Free Syrian Army factions. In turn, the Free Syrian Army factions ended up in the hands of opportunistic elements who, according to the Syrian researcher Youssef Sadaki, “had no strategy and no vision; they were just fighting to be powerful and to get back in the spotlight.”25

In early 2012, the Islam Company had emerged as one of the most powerful factions in Douma and in all of the Eastern Ghouta. To emphasize its strength, Alloush renamed his group the Islam Brigade, or Liwa’ al-Islam. Its identity was gradually becoming that of a big-tent Islamist movement seeking to represent the Ghouta region’s conservative Sunni population and aspiring to a national role in Syria, though the top-level leadership remained firmly in the hands of Alloush and his Douma Salafis.

An important source of influence for Zahran Alloush was his family connections with Salafi clerics in the Arab countries of the Gulf, which he leveraged to improve the Islam Brigade’s financial standing. Several Syrian expats and foreign clerics dedicated themselves to collecting money on his behalf in Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. Among the best known was Adnan Arour, a Riyadh-based Syrian televangelist who had met Alloush during his days as a student in Saudi Arabia. Originally from Hama, he had become immensely popular among Syrian rebels and Islamist-leaning demonstrators for his feisty and unapologetically Sunni-sectarian denunciations of Assad. Many expat Syrians and other Islamist supporters of the uprising donated money to Arour without knowing his precise affiliations inside Syria, and he seems to have passed on considerable funds to Alloush.26 The Islam Army’s deep pockets were an important reason for its growing power, according to Sadaki. “When money started rolling in to Zahran Alloush and he was able to pay his soldiers $150 or $200 a month, which is a lot inside the Ghouta, people left [the other Douma factions],” he said.27

Another source of influence for Alloush was the arms trade. Several local alliances had been set up in the Damascus region under the Free Syrian Army brand, such as Colonel Khaled al-Habbous’s Military Council of Damascus and Its Countryside, created in March 2012, and Captain Abdel-Nasr Shmeir’s Revolutionary Military Council of the Eastern Ghouta, created in September 2012. These councils were organizationally unstable and failed to inspire much loyalty among the fighters, but some of them played a role in channeling arms from foreign sponsors.

According to Habbous, his Military Council began to serve as a channel for arms shipments from Turkey in mid-2012.28 Large amounts of weapons and ammunition had by then been collected in now-stateless Libya by Syrian exiles and the Muslim Brotherhood, with assistance from Libyan Islamists, Qatar, and the Turkish government. The first leg of the arms transports seems to have been handled by the Farouq Battalions, a group that had emerged in the Homs region in 2011 and now controlled areas on the Syrian-Turkish border. To reach the areas east of Damascus, the smugglers then had to bring their cargo from Homs through the mountainous Qalamoun region.29

Alloush refused to join the Military Council, allegedly because he saw the defected officers as impious ex-Ba’athists, but he collaborated with the group in order to tap into its arms smuggling network. According to Habbous—who, it should be noted, has made a number of unsubstantiated accusations against the Islam Army—Alloush was made responsible for distributing weapons in the Ghouta, but ended up diverting most of the cargo to his own allies. “In this way, the Islam Company started to develop,” Habbous said, “because Sheikh Zahran was the one—or rather one of the members of the committee—that distributed the arms.”30

On July 18, 2012, the Islam Brigade gained national (and international) attention by claiming responsibility for the assassination of several senior security officials at the National Security Office in Damascus, including Bashar al-Assad’s brother-in-law General Assef Shawkat and Defense Minister Dawoud Rajha.31 The incident remains murky and it is possible that this was either an opportunistic false claim on Alloush’s part, or an operation executed by someone else—such as a foreign intelligence service—who credited the Islam Brigade in order to escape attention. Whatever the case, the Islam Brigade was able to use its newfound notoriety to attract additional funds and recruits.

In its claim of responsibility for the July 18 attack, the Islam Brigade had still referred to itself as part of the Free Syrian Army, but in the following months it dropped this label. Free Syrian Army symbols had been in general use among the Syrian rebels, but by mid-2012 they were falling out of fashion as the main factions of the insurgency began to emphasize a religious and sectarian Sunni discourse. The Free Syrian Army brand remained in usage as a general term for the insurgency and would later reemerge as a collective name for Western-approved factions, but Alloush’s group chose to instead double down on its Islamist identity.

2013: Rise of the Islam Army

As the conflict entered its third year, Zahran Alloush was becoming a figure of national importance. Drawing on old contacts from Sednaya Prison, he developed a broad network in northern Syria and Turkey, where some of his former fellow inmates were present in the leadership of groups like Ahrar al-Sham and the Nusra Front. But his primary focus seems to have been closer to home.32

The Assad government and its security apparatus had been expelled from Alloush’s hometown of Douma in late 2012, creating a power vacuum that had yet to be filled. Alloush’s main rival in this area was the Douma Martyrs’ Brigade, a group with roots in the early, nonreligious rebel networks that had led the capture of Douma. Although their conflict was not primarily about ideology, Alloush’s growing power had prompted a closing of ranks among secular activists and rival religious groups, such as Sufi clerics who feared the rise of Salafism. The Douma Martyrs’ Brigade became the primary beneficiary of this backlash, and the two factions began to compete for power in Douma by trying to attract smaller armed groups to their respective sides.

These power struggles seem to have played out almost exclusively within the opposition itself, with little involvement from the wider population. All factions clearly had some grassroots influence and there was considerable support for the rebellion as such, but none of the commanders seemed to have developed a genuine civilian following or an organized popular base. It was not even clear that they were trying. With rare exceptions, the rebels did not form political parties, nor did they stage elections or seek to mobilize the wider population for their purposes through organizations or public rallies, except for the ongoing Friday demonstrations against Assad. There were attempts at political and associative action, but these mostly seemed to be initiatives from civilian activists who had no clout among the armed factions. And though the Islamists worked to influence public opinion through the mosques and missionary outreach, the overall impression was that of an insurgency whose commanders simply took popular support for granted.

The lack of a central authority in Douma after the expulsion of the regime had led to growing lawlessness. Several of the armed groups now ran their own sharia courts and private prisons. Some rebel commanders were becoming infamous for thuggish behavior and criminality and there were sporadic bouts of infighting. As the economic situation and local security deteriorated, the rebels seemed to realize that their internal divisions and failure to govern had become a liability.

In March 2013, rebel commanders in Douma gathered to create the Douma Mujahideen Council in order to rule the city and tamp down intra-factional conflict.33 Though the council included many small factions, it was dominated by and polarized between the Islam Brigade and the Douma Martyrs’ Brigade. The two factions had decided to divide power between themselves, with the Douma Martyrs’ Brigade commander Abu Subhi Taha becoming president of the alliance and Zahran Alloush taking up leadership of its religious advisory board, the Shura Council.

However, the balance of power soon tilted in Alloush’s favor, as smaller factions began to join the Islam Brigade. There seem to have been several reasons for this, including the organizational talents of Alloush’s team and his support from Douma’s Salafi civil society networks. But another reason was the rising foreign support for the Islam Brigade.

In mid-2013, or perhaps earlier, a Kuwaiti charity called the Council of Supporters of the Syrian Revolution had emerged as one of Alloush’s most important foreign sponsors.34 It had been set up the previous year under the leadership of the Kuwaiti parliamentarian Mohammed Hayef al-Moteiri, and it collected a great deal of money. For example, a twenty-four-day fundraising drive in February 2013 listed a goal of 500,000 Kuwaiti dinars, or $1.75 million.35 Much of these funds went into humanitarian projects, but the Council of Supporters did not try to hide the fact that they also financed armed factions. For example, the group’s June 2013 fundraiser was called “The Mobilization Campaign to Support the Mujahideen in Syria,”36 and among its projects was the building of an arms factory in the Eastern Ghouta.37

Over summer and autumn 2013, the Council of Supporters pumped cash into Alloush’s coffers with the unspoken aim of trying to engineer a Ghouta-wide supergroup under his leadership, reportedly directing 70 percent of their donations specifically to the Islam Brigade. On September 29, Alloush declared the merger of the Islam Brigade and forty-two other armed groups into what would be called the Islam Army (Jaysh al-Islam).38 Other small factions quickly decided to bandwagon with Alloush, and by November, the Islam Army claimed to comprise no fewer than sixty rebel factions. Though this was probably an exaggeration, there was no doubt that the Islam Army had grown into a very powerful group.39

The summer and autumn of 2013 allegedly also marked the start of serious Saudi support for Alloush, possibly through or in coordination with the Kuwaiti network. “Saudi tribal figures have been making calls on behalf of Saudi intelligence,” a Damascene rebel commander told Reuters after the Islam Army merger. “Their strategy is to offer financial backing in return for loyalty and staying away from al-Qaeda.40” The suspicions of a Saudi connection were further strengthened when it emerged that Alloush had quietly slipped out of the Eastern Ghouta to visit Saudi Arabia for the hajj pilgrimage right after the announcement of the Islam Army.41

However, Alloush’s links to Riyadh often seemed to be exaggerated by his rivals on the jihadi end of the Salafi spectrum, who were sensitive to and fearful of any Saudi intelligence involvement. In fact, he seemed to be taking money from many sources. There had previously been hints of a Qatari connection, and it seems quite possible that the Islam Army still relied on diverse and mostly nongovernmental sources of funding.

Whoever was responsible for his rise, there could no longer be any doubt that Zahran Alloush was now the most powerful man in the Eastern Ghouta and that he was steadily getting stronger.

Whoever was responsible for his rise, there could no longer be any doubt that Zahran Alloush was now the most powerful man in the Eastern Ghouta and that he was steadily getting stronger. He leveraged his military might by offering protection to wealthy businessmen and minor commanders, while using his money to set up charities to curry favor with the population, fund friendly preachers and mosques, and lure new recruits with weapons and a steady salary.

With Alloush now too big to share power equitably with anyone, the power-sharing arrangements agreed in his hometown through the Douma Mujahideen Council broke down. In October 2013, the council president and Douma Martyrs’ Brigade commander Abu Subhi Taha expelled Alloush from the leadership of the coalition. The putsch was cheered on by secular activists and perhaps also by rival foreign powers, but Alloush had no intention of allowing himself to be legislated out of power. He simply pulled his followers out of the council, which duly collapsed. Abu Subhi Taha was temporarily cowed, but continued to plot his revenge.

The following month, virtually all of Alloush’s regional rivals gathered into yet another short-lived alliance, this one called the Greater Damascus Operations Room, which had been conceived of as a coordination structure for both the Western and the Eastern Ghouta.42 Though it was an impressive project on paper, it didn’t work well and it ultimately failed to balance the rise of Alloush. The Eastern Ghouta had now been sealed off from surrounding territories by the army siege and, inside its enclave, the Islam Army was too powerful to be isolated. Left as the biggest fish in a shrinking pond, Alloush was instead finally able to impose himself on the smaller factions, first in Douma and then in the wider Eastern Ghouta.

Repression and Controversies

The Islam Army’s growing power brought increased scrutiny of its humanitarian track record, which was not comforting. The chaos that had plagued the enclave was giving way to an order of sorts, but it was built on a balance between armed factions and on repressive policing. Alloush had created a security branch that was beginning to spread its influence far outside Douma, often setting up offices to encroach on the turf of smaller factions. There were occasional military skirmishes, while civilian opponents of the Islam Army could face harassment, threats, and beatings. The group ran several private prison facilities, such as the Repentance Prison (Sijn al-Toubah), which gained a terrifying reputation for torture and abuses.

“Of course the siege and the indiscriminate attacks of the government are the most important part of the destruction of these areas, but it was also due to the behavior of these armed groups,” recalled Bassam al-Ahmed, a former spokesperson for the Violations Documentation Center, a human rights group based in the Eastern Ghouta. “It is no longer a secret that this experience has failed to bring anything better than Assad in that respect. By 2016, a lot of activists have been forced to leave. Many of them have been abducted, kidnapped, and tortured.”43

The repression also touched Ahmed’s own group. In December 2013, the Violations Documentations Center’s founder and president, the well-known human rights lawyer Razan Zeitouneh, was kidnapped in Douma along with her husband Wa’el Hammada and two other secular democracy activists, Samira Khelil and Nazem Hammadi.44 Never heard from since, it is widely believed that they were murdered after capture. Though the Islam Army has denied involvement, human rights groups and relatives of the “Douma Four” hold Alloush responsible, pointing to a history of threats and harassment against the activists by his security officers.45 A young and charismatic intellectual who had publicly advocated for democracy even before 2011, Razan Zeitouneh was an iconic figure for much of the secular opposition, and she was closely connected to Western human rights monitors. Her disappearance came to define Zahran Alloush in the eyes of many liberal Syrians and foreign observers, and it would later obstruct his attempts to clean up the Islam Army’s image and build relations with the West.

The Islam Army’s politics were also coming in for criticism. In line with his religious beliefs, Alloush was an out-and-out opponent of democracy and he indulged in menacing Sunni-sectarian rhetoric that sometimes bordered on the genocidal. For example, in a September 2013 propaganda video, he had vowed to cleanse the Levant from the “filth” of Shia Islam.46 Among secular Syrian intellectuals and pro-opposition Western observers, he was now being held up as an example of the “bad rebel.”

In fact, such sectarian notions had become mainstream within the armed insurgency two years into the war. Alloush’s opinions were at odds with the idealized democratic revolution envisioned by the Western media, Western officialdom, and the democratic opposition itself, but among the fighters on the ground, Islamist values predominated and there was no evidence that Alloush’s anti-Shia statements had hurt his standing. If anything, they seemed to be broadly shared and appreciated, which was presumably why they were part of the Islam Army’s public propaganda in the first place.

Indeed, rather than shunning him, the other major factions in Syria sought his support. On November 22, 2013, the Islam Army created an alliance known as the Islamic Front alongside some of the most powerful factions in the country, including the Tawhid Brigade of Aleppo, Idlib’s Suqour al-Sham, and the large Salafi group Ahrar al-Sham,47 all of whom espoused Islamist views similar to those of Alloush. The Islamic Front alliance mattered greatly in northern Syria, where the Islam Army had by now acquired subfactions operating along the Turkish border, but it had little direct impact on the politics of the Eastern Ghouta. It did however raise Alloush’s profile as a top-ranking opposition leader on the national level, a status that no other rebel commander in the Damascus region could aspire to.

2014: Uniting the Eastern Ghouta

In early 2014, most of the groups in the Eastern Ghouta seemed to accept that Zahran Alloush had become first among equals inside the enclave, despite vocal opposition from unrelenting rivals like his old competitors in Douma, Abu Subhi Taha, and Abu Ali Khibbiyeh.

After two years of failed coalition building, it was this grudging admission of Alloush’s leading role that finally made broad coalitions possible, by creating a clear center of gravity. It paved the way for a solution of the now dangerously pressing problem of how to govern the enclave, which had remained in a state of semi-anarchy since the expulsion of Assad’s government two years prior, with each rebel faction running its own affairs the way it saw fit and a chaotic tangle of sharia courts and revolutionary councils vying for influence over legal and administrative matters.48

On June 24, 2014, the Islam Army and sixteen other rebel factions announced the creation of the Eastern Ghouta’s Unified Judicial Council, the first enclave-wide union of rebel-backed Islamic courts. Led by a panel of religious scholars, its role would be to impartially administer sharia law across the enclave through a centrally coordinated system of regional courts and institutions. Unlike some of the other post-Assad judicial systems created in the Eastern Ghouta, the Unified Judicial Council had no trained lawyers or judges on its governing board, only Islamic scholars. In practice, most of the sheikhs represented specific armed factions, in order to secure support from these factions for the council.49 And it worked: at its creation, the Unified Judicial Council was backed by every major faction in the Eastern Ghouta, though the al-Qaeda-aligned Nusra Front soon broke off to run its own sharia courts instead.

On August 27, 2014, this was followed by the creation of a Unified Military Command, which became the highest military and civilian authority in the Eastern Ghouta. It was founded by five of the enclave’s most powerful factions: the Islam Army, Ajnad al-Sham, Failaq al-Rahman, the al-Habib al-Mustafa Brigades, and the Eastern Ghouta branch of Ahrar al-Sham. Alloush headed the command, with the Ajnad al-Sham leader Yasser al-Qadri as his deputy and Failaq al-Rahman’s Abdel-Nasr Shmeir as his field commander.50

Qadri, also known as Abu Mohammed al-Fateh, was born in 1983 in Damascus to a family from Reyhani near Douma. A young religious scholar with a degree from Cairo’s al-Azhar University, he had also studied under several famous Damascene sheikhs and his family had strong links to the Muslim Brotherhood.51 Ajnad al-Sham matched the background of its leader: it had been formed in November 2013 as a project of the traditionalist Damascene clergy, possibly also with support from the Muslim Brotherhood.52 Backed by a broad array of Sufi and traditionalist Islamic scholars, many of whom were hostile to Salafism, it had enough ideological and financial muscle to retain its independence vis-à-vis the Islam Army, but it now grudgingly accepted to work under Alloush’s command.

Captain Abdel-Nasr Shmeir, also known as Abu al-Nasr, was born in 1977 in the city of al-Rastan near Homs, but had married into the family of a religious sheikh in the Eastern Ghouta. Unlike his fellow rebel leaders, Shmeir was neither a student nor a scholar of Islam, instead serving as an army captain until defecting in April 2012. In August 2012, he headed an armed group known as the al-Bara Battalion, which made headlines by kidnapping forty-eight Iranians on pilgrimage to the Sayyeda Zeinab shrine; Shmeir claimed that they were Iranian intelligence officers. The Iranians were released in October that year in a murky deal that involved a prisoner exchange and reportedly also a large ransom payment.53 These funds seem to have helped Shmeir remain independent of Alloush and develop the al-Bara Battalion into the much-larger Failaq al-Rahman network, which was created in late 2013. Shmeir drew on his military background to emphasize nationalist themes and a Free Syrian Army identity, seemingly trying to position Failaq al-Rahman as the Eastern Ghouta’s non-Islamist alternative.54

The Unified Military Command had gathered the most powerful factions in the Eastern Ghouta, with one very significant exception: the Nusra Front, al-Qaeda’s branch in Syria. A host of lesser commanders also refused to abide by its rules, notably the disgruntled Douma rebels Abu Subhi Taha and Abu Ali Khibbiyeh, both of whom had a bone to pick with Alloush. One source later estimated that “close to half” of the enclave’s rebels had stayed outside of the Unified Military Command at the time of its formation.55 Alloush and his partners clearly had their work cut out for them if they wanted to use the new alliance to control the enclave.

The armed groups jealously guarded their military and financial independence, and despite their public vows to let the Unified Judicial Council handle all legal matters, they continued to run private prisons and security forces.

Perhaps a bigger problem was that the members themselves often refused to abide by the rules of the Unified Military Command. The armed groups jealously guarded their military and financial independence, and despite their public vows to let the Unified Judicial Council handle all legal matters, they continued to run private prisons and security forces. They also continued to wrestle over local resources and occasionally skirmished with each other. Even so, the new institutions did provide a useful basis for joint action and the institutionalization of political life in the Eastern Ghouta—and Alloush was already making plans for how to deal with the dissenters who refused to join.

Destroying the Anti-Alloush Opposition

In September 2014, soon after the creation of the Unified Military Command, around twenty small groups that had refused to endorse the new system coalesced into two new coalitions, known as the Umma Army and Failaq Omar.56

The most pugnacious of these alliances was the Umma Army. Led by the veteran Douma rebel Abu Subhi Taha and his associate Abu Ali Khibbiyeh, the Umma Army was a hodgepodge of Free Syrian Army groups and local gangs held together mostly by their shared hatred of Zahran Alloush. Some of its members were linked to the Southern Front of the Free Syrian Army, a rebel coalition on the border with Jordan that received support from the Jordan-based and United States-backed Military Operations Center, or MOC.

Both Taha and Khibbiyeh had played a pioneering role in the early uprising in Douma and they were well-known figures in their home community, but they were also associated with smuggling and criminality. Unable to build major popular support or construct an effective movement, they had struggled in sullen opposition to the Islam Army since 2012. Among other things, they had offered protection to some of Douma’s secular opposition leaders, though it is less clear whether this was a question of genuine political beliefs or if they simply wanted to spite Alloush. In this way, they had emerged as central figures in the anti-Islam Army opposition in Douma.

After his marginalization at the hands off Alloush in 2012, “Abu Ali Khibbiyeh didn’t have that many people with him anymore, but by the end of 2013 and in 2014, people were drawing closer to Islamic and Salafi thoughts, and some opposed this,” explained Youssef Sadaki, of the Orient Research Center. “For them, it was not about whether Abu Ali Khibbiyeh was a bad person or not, or about whether he smuggled and stole. It was about Zahran Alloush becoming all-powerful and trying to finish off everyone else. So people gathered around Abu Ali Khibbiyeh.”57

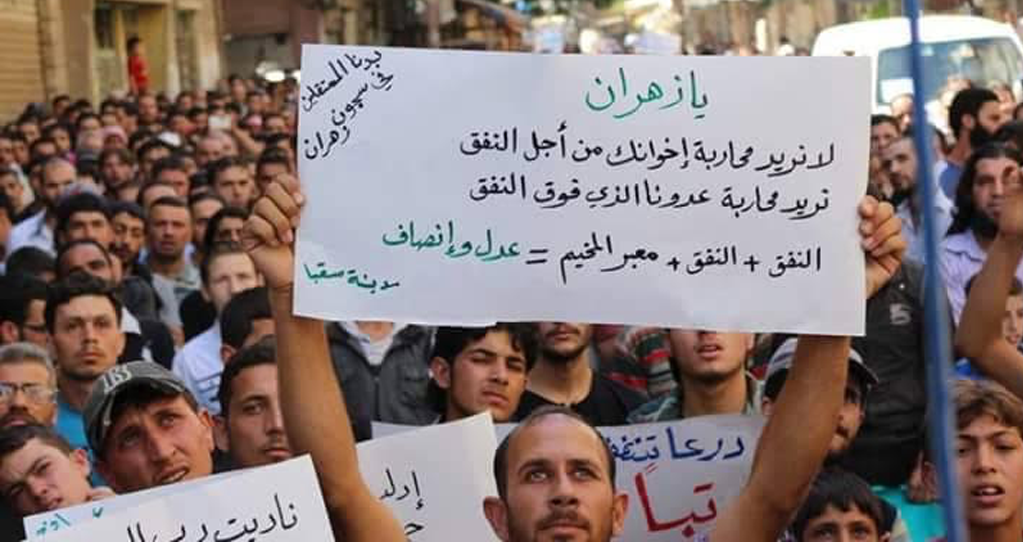

When Zahran Alloush learned of the Umma Army’s challenge to his unity project, he reacted with outrage, threatening its leaders and stating that the Eastern Ghouta could not suffer having “two heads on the same body.”58 Clashes between the groups erupted almost immediately. In late October 2014, the Umma Army agreed to recognize Alloush’s leadership of the Unified Military Command, but the conflict continued.59

One front of the struggle appears to have played out at the Wafideen Crossing near Douma, where Abu Ali Khibbiyeh and his allies were running a lucrative siege-busting business with the complicity of traders and military commanders on the government side. When the Islam Army moved in and began arresting Umma Army members, apparently also seizing some of the goods that had come through the crossing, the Syrian government shut down all trade. This sparked an instant humanitarian crisis in the Eastern Ghouta. The Umma Army blamed Alloush, slamming him as a dictator and a war profiteer who had stolen food from the starving. He in turn castigated the Umma Army leaders as drug dealers, smugglers, and agents of both the Islamic State and the Syrian government.60 To further weaken Alloush, Umma Army members in Harasta decided to stop the Islam Army from using their smuggling tunnels to bring in otherwise unavailable supplies.

As the crisis grew, the Umma Army encouraged demonstrations against Alloush, accusing him of hoarding food and of being Assad’s silent partner in the siege. In mid-November 2014, armed demonstrators stormed Islam Army warehouses in Douma, egged on by the Umma Army. “The guards fired on us directly, which prompted some protesters to fire back, leading to serious injuries among some residents,” a local activist told the online journal Al-Monitor.61

However, if the Umma Army leaders had thought that they could force Zahran Alloush to share power, they had badly misjudged the man. In late December 2014, the Islam Army declared that it would now “cleanse the land of corrupt filth” and launched a ferocious, no-holds-barred military assault on the Umma Army.62 Zahran Alloush’s partners in the Unified Military Command publicly criticized him for acting outside the framework of the joint institutions, but none of them intervened to defend the Umma Army on the battlefield.63

Left alone to face Alloush, the Umma Army did not stand a chance. The Islam Army leader later claimed to have jailed thirteen hundred members of the group.64 Abu Subhi Taha’s fate remains unclear, but the Islam Army later released a video in which a subdued-looking Abu Ali Khibbiyeh, who had been captured after a manhunt in early January 2015, confessed to being a criminal, a narcotics trader, and a homosexual.65 According to some reports, he was executed nine months later.66

Alloush dealt with Failaq Omar, the other faction created in September 2014 that opposed him, in a more cautious fashion. The group had its roots in the Marj area on the southern end of the enclave and seems to have been a local enterprise linked to Bedouin clans and hardline Islamists. Starting in July 2014, the Islam Army’s secret police had waged an unsparing war against the Islamic State, which escalated in 2015 as Alloush declared that even ideological sympathy for the jihadists would be considered a crime.67 Some Islamic State cells were apparently operating inside Failaq Omar, which exposed the group to repeated crackdowns. Weakened and wary of suffering the same fate as the Umma Army, the remaining leaders of Failaq Omar finally gave up and joined the Islam Army in April 2015.68

Meanwhile, another potential rival to Zahran Alloush collapsed in a complicated split. In March 2015, Ahrar al-Sham’s local branch in the Eastern Ghouta was bought up by Failaq al-Rahman, though some members immediately backed out and sought to revive the Ahrar al-Sham brand.69 A dispute over ammunition stockpiles and bases followed, in which the Islam Army sided with Failaq al-Rahman—possibly in return for some of the spoils. The Unified Military Command then sought to enforce a February 2015 ban on the creation of new factions, which effectively outlawed Ahrar al-Sham in the Eastern Ghouta.70 Fearing complete isolation and eager to aid anyone that opposed the Unified Military Command, the Nusra Front stepped in to protect the dissidents. However, according to the Syrian researcher and opposition member Ahmed Aba-Zeid, this rump faction of Ahrar al-Sham comprised only about one hundred fighters, meaning that Ahrar al-Sham was more or less finished as an independent force in the Eastern Ghouta.71

Since the smaller groups were now formally banned from creating new alliances or seceding from old ones, the insurgency began to solidify at a higher pace. Most of the remaining mini-groups were pulled into the orbit of one of the “big three” members of the Unified Military Command: the Islam Army, Ajnad al-Sham, or Failaq al-Rahman.72

As the factional muck slowly drained away, only the Nusra Front remained as an explicit challenger to the new system. It continued to run its own sharia courts outside the Unified Judicial Council system, to which citizens could turn if they didn’t like the courts provided by Alloush and his allies. Alloush repeatedly stated that this state of affairs could not continue and that he would not permit anyone to run a legal system outside the United Judicial Council.73 The Unified Military Command was also mobilized to demand that the Nusra Front shut down its courts and submit to the Unified Judicial Council.74 But the jihadis refused, and Alloush did not, in the end, move against them militarily.75

This exception aside, the new institutions were gaining considerable traction. By early 2015, every major faction in the Eastern Ghouta except the jihadis had endorsed them. Though senior members of the rebel factions were practically untouchable, civilians were now largely being referred to the sharia courts of the Unified Judicial Council. The homogenization of the enclave also proceeded apace on the social level, through the enforcement of strict religious norms. In summer 2015, a new religious police appeared on the streets of Douma to promote Islamic morals and sharia law. Though critics complained that it was a way for the Islam Army to unilaterally impose its worldview on others, the group’s leaders could now claim to act on behalf of the Unified Judicial Council.76

Yet, while Alloush used the new institutions to legitimize and magnify his own power, he refused to be constrained by them. He had not consulted his allies ahead of the crackdowns on the Umma Army and the Islamic State, and when the Unified Judicial Council asked for access to his own prisons or tried to investigate the fate of Abu Subhi Taha, the Islam Army shrugged it off.79

As for the Islam Army, it had now developed into a large and well-equipped military force commanding thousands of fighters. Already officially named the Eastern Ghouta’s supreme commander, Zahran Alloush seemed to be seeking the role as its undisputed ruler. In April 2015, the Islam Army released video footage of a large military parade, with long rows of uniformed soldiers and tanks marching past a parade stand where Alloush sat on a chair flanked by his lieutenants.80 More than anything, it seemed designed to emulate a traditional Arab army, with Alloush in the role of a traditional Arab president.

The Economy of a Siege

The siege imposed on the Eastern Ghouta in 2013 played a major role in the evolution of its politics. Government-imposed restrictions on trade and aid deliveries created a very particular war economy, which left rebel factions dependent on the government but also increased those factions’ influence over the population. In the climate of scarcity created by the siege, the small number of semiofficial frontline crossings and tunnels that could be used to import goods provided the government with new leverage and engendered new forms of competition among the rebels. Actors on the government side profited from the siege and acquired a vested interest in maintaining it, and rebel commanders also increasingly adapted to the siege economy.

Understanding the background and functioning of this peculiar siege economy is crucial to understanding the Eastern Ghouta’s rebel politics, and it provides an instructive example of how financial constraints and opportunities can shape the political and military situation in counterintuitive ways.

As has been described above, the government initially laid siege to the Eastern Ghouta after its capture of Oteiba in April 2013. In the following months, the government moved to seal the main entry routes to the enclave at Mleiha in the south and near the Wafideen Camp in the north. Some trade quietly continued, but the siege was further tightened and expanded into a comprehensive economic blockade in early 2014, when the army recaptured Mleiha and took steps to fully close the Wafideen Crossing. Later in 2014, a limited trade resumed via progovernment businessmen and their rebel intermediaries. But while this allowed food and fuel prices in the enclave to stabilize at a high level, supply has remained spotty and prices sometimes spike due to fighting, checkpoint closures, the destruction of smuggling tunnels, or market manipulations. Civilians have remained trapped inside the enclave, unable to cross the frontlines and prevented from leaving by both government forces and local rebel groups, notably the Islam Army.81

The blockade has caused severe human suffering inside the enclave. For an example of the price inflation, the pro-opposition Douma Coordination Group published the following comparison between the Eastern Ghouta and what it termed “Occupied Damascus” in March 2015. (Units differ from product to product, while prices are listed in Syrian pounds.)82

| Table 1. Price of Goods Comparison, Eastern Ghouta vs. Damascus, March 2015 | ||

| Product | Eastern Ghouta | Damascus |

| Sugar | 2750 | 120 |

| Eggs | 5100 | 750 |

| Bread | 750 | 35 |

| Tea | 8000 | 1200 |

| Heating Oil | 1100 | 120 |

| Potatoes | 1300 | 90 |

| Lentils | 1600 | 125 |

| Source: Posted on the author’s Twitter account on March 4, 2015. | ||

The rebels did what they could to counter the effects of the new policy, including trying to grow more food inside the besieged area and using aid money to subsidize certain goods. Nevertheless, the blockade crippled normal life in the Eastern Ghouta and it had a severe impact on the civilian population, which suffered from malnutrition and the depletion of medical supplies. The opposition-friendly Syrian American Medical Society estimates that more than two hundred civilians in the enclave died from a lack of food or access to medical care between October 2012 and January 2015,83 and Amnesty International concluded that the Syrian government’s blockade on food and medicine in the Eastern Ghouta amounted to a crime against humanity.84

Apart from its effect on the civilian population, the blockade has had a profound impact on the structure and cohesion of the Eastern Ghouta insurgency. On the one hand, new types of conflict emerged, as rebel commanders jockeyed for control over scarce resources, smuggling routes, and government-approved imports. On the other hand, those who successfully monopolized some facet of the siege economy profited greatly and could expand their influence in the enclave. Government-connected businessmen have similarly used the siege to gain influence in Damascus and over the rebels. Army and intelligence chiefs have enriched themselves at checkpoints controlling access to the enclave, and the government also seems to have exploited its ability to turn trade on and off in order to sow enmity among the rebels. “Keep in mind that the regime wants to strengthen a certain faction at the expense of other factions,” said a member of a rebel group operating in the Damascus region. “So it will open a crossing and call it civilian or a humanitarian, and then it turns a blind eye to what passes through there.”85

The Million-Pound Checkpoint

Though neither side has been eager to talk about it, a deal emerged in 2014 through which select progovernment traders are allowed to bring goods to the frontline near the army-controlled Wafideen Camp.

Though the arrangement has occasionally broken down or been temporarily suspended by the government, the so-called Wafideen Crossing has remained the most important outside source of food for the enclave since then and it is often described as the “lung” through which the Eastern Ghouta breathes. In June 2015, a local trader working the Wafideen Crossing explained to Amnesty International how it operates:

To leave Douma I need to pass by a non-state armed group checkpoint then I drive for a couple of minutes passing by an area that is not controlled by anyone. Then I pass by three checkpoints controlled by the Air Force Intelligence and State Security forces. I reach al-Wafedine camp where I buy the food. I do not leave the truck. Two women with me in the car transfer the food and non-food items to the truck and pay the security forces. For every item I pay a price equivalent to eight or ten times the price in central Damascus.86

Commanders on both sides of the front will demand a cut from the trade, turning the enclave’s captive market into “a source of monetary support for the regime,” but also, paradoxically, for the rebels.87 Consumers inside the Eastern Ghouta end up paying enormously inflated prices even on larger shipments, as described in a 2015 report from the London School of Economics:

Assume a businessman in Ghouta wants to buy a ton of sugar which costs USD 0.5 per kilo in Damascus; he would then coordinate with a businessman in Damascus who is connected with certain security officials in the government and would then source the sugar and deliver it across the government-controlled checkpoint ‘One Million Crossing’ entering the ‘exchange zone’. To make it there, certain fees have to be paid. The businessman from Ghouta, who in turn has to be connected with the right commanders in the opposition, enters this zone after crossing the opposition-controlled checkpoint, completes the deal, receives the sugar then enters Ghouta again after paying fees at the opposition controlled checkpoint. When the time is right, this businessman would then sell the sugar for the highest price to smaller dealers and stall sellers and finally to arrive to the end user with the price of USD 11.8 per kilo, a twenty-four fold increase in price. To put it differently, for each ton of sugar which costs USD 500 a staggering USD 11,265 is going to feed this well-established network of war profiteers and violent actors.88

On the government side, the crossing has become so profitable that it is known in Damascus as Hajez al-Milyoun “the Million Checkpoint,” in reference to the earnings of the soldiers manning it.89 The checkpoints do not seem to be manned by the regular army. Rather, various sources name different security and military branches as being in control of the trade, with most pointing to either the Air Force Intelligence Directorate, or the Republican Guard, or both.90

On the rebel side, the Douma–Wafideen route was at one point controlled in whole or in part by the Free Syrian Army faction of Abu Ali Khibbiyeh. In the autumn and winter of 2014, Zahran Alloush sent troops to seize Khibbiyeh’s checkpoints, as part of his crackdown on the Umma Army. Since then, the Wafideen Crossing has been in Islam Army hands. The group reportedly exercises strict control over food imports. Traders are forced to acquire signed permits if they wish to bring food into the Eastern Ghouta, and they must sell and offload all foodstuffs at Islam Army-protected warehouses. In this way, the Islam Army and its surrogate businessmen have gained near-monopolistic control over food imports. However, traders are allowed to bring nonfood items, like cigarettes, into the Eastern Ghouta and sell these privately at a higher profit.91

Eastern Ghouta activists have accused the Islam Army of taking a 30 percent cut from each shipment and of making “unimaginable” profits,92 but the Islam Army denies having any economic interest in the trade. The Wafideen Crossing “is open only to some civilians who transport small amounts of certain goods by foot, or to humanitarian convoys, as well as to a trader who runs a barter operation through the crossing. He brings out certain products from the Ghouta and brings in some of the things it needs,” said Mohammed Bayraqdar, a member of the Islam Army’s political office. “The role of the Islam Army in all of this is simply to provide security, so that agents of the regime do not infiltrate via the crossing.”93

The Cheese King

The trader that Bayraqdar mentioned is Mohieddine Manfoush, also known as Abu Ayman, a little-known local businessman who has emerged as the most important figure in the Eastern Ghouta’s siege economy.94 Manfoush hails from a family in Mesraba, southwest of Douma, but although he reportedly still visits the Eastern Ghouta sporadically, he resides in government-held territory and his offices are in the western suburb of Mezzeh. His family controls the Manfoush Trading Company, which is a major supplier of cheese, yoghurt, and other dairy products for the markets in Damascus under the brand name Almarai. The Manfoush family factory is located in Mesraba, and remains in operation despite the war and the siege.

According to Youssef Sadaki, who has studied the Eastern Ghouta’s siege economy,95 Manfoush began to provide support for bakeries and bring in wheat to the Eastern Ghouta in 2014, as the government tightened its siege. He later began to pay stipends to teachers in his hometown, Mesraba, and the nearby village of Medyara. Eventually, he emerged as a middleman between the rebels and the markets in Damascus, negotiating with Syrian military commanders to take in truckloads of food, fuel, and other civilian supplies through the Wafideen Crossing, while bringing out his own dairy products for sale in Damascus. He thus established himself as the most important supplier of basic goods and food for hundreds of thousands of civilians in the enclave. Sadaki claimed Manfoush has some two thousand employees and has even set up a force of two hundred armed men to guard his farm and his properties in Mesraba, which seems to have been spared most of the airstrikes that have devastated other Eastern Ghouta towns. He is now said to be fabulously rich.96

It is not clear who is providing cover for Manfoush’s operations in Damascus, although the government is clearly well aware of his involvement with its Islamist enemies in the Eastern Ghouta. Given the sensitivity of the issue, there is no doubt that his business has been approved by very senior figures in the regime, and it seems likely that they, too, must benefit financially from it.97

Whoever his contacts are on the government side, Manfoush has clearly built a strong relationship with the Eastern Ghouta insurgents as well as with the civilian population, where many reportedly seek his counsel to access services or other favors. Though these sentiments are perhaps not widely shared in the civilian population, he has been described as “beloved by both the opposition and regime.”98 Some rebels even express surprise at the notion that Manfoush could be perceived as a progovernment figure, apparently considering him to be one of their own who just happens to live and work on the other side. “No, Abu Ayman does not take part in the revolution,” said Wa’el Olwan, the Failaq al-Rahman spokesperson. “He has continued to work in Damascus and reached a deal between the revolutionaries and the regime. This allows him to work with both sides and, yeah, of course he makes money from it.”99

The Islam Army is at pains to deny that they have any stake in Manfoush’s operations at the Wafideen Crossing, but the group doesn’t hide that it appreciates his role. “Manfoush does not serve the Islam Army, he serves the Ghouta in its entirety,” said the Islam Army official Mohammed Bayraqdar. “Our interests are in harmony with the interests of the people and our relationship is merely that of facilitating his services. If there were another person [who performed the same function], we would provide the same services to him in return for his services to the people of the Ghouta.”100

Whatever his motives or the nature of his relationship to the insurgent groups and the Assad regime, all sides seem to agree that Manfoush has emerged as a major powerbroker in the Eastern Ghouta and that his imports via the Wafideen Crossing are now crucially important to sustain life in the enclave. Quite possibly, he is now also a person of some importance in Damascus, and it seems likely that he could play a significant role in future truce negotiations between rebels and the government, and perhaps also in a postconflict settlement. Yet, he has only been mentioned in a small handful of articles in the Arabic press and hardly at all in English. Indeed, his Wafideen business has gained little attention even in Syrian opposition publications.

While much therefore remains unknown about his exact role in the Eastern Ghouta’s siege economy, Mohieddine Manfoush appears as an interesting example of how Syrian entrepreneurs operate in the gray zones of politics and the war economy, and how they can emerge as powerful actors on the ground without even registering in the politicized narratives that dominate media coverage of the conflict.

The Tunnel Trade

Apart from the Wafideen Crossing, the Eastern Ghouta has been supplied through a system of secret tunnels and semi-informal frontline crossings. While the crossings can bring in a far greater volume of trade, the tunnels serve to import goods that are restricted or banned by the government (including fuel, medical supplies, and arms), to move people in and out of the enclave, and to challenge and undercut food prices set by the Wafideen monopolists. Several different factions have had access to tunnels, but much of the traffic has also taken place in collaboration between two or more groups, sometimes leading to ideologically awkward alliances. Repeated battles between opposition groups erupted from 2014 to 2016 over profit sharing, charges of price dumping, and, more straightforwardly, over who should control which tunnel. Though the scope of the traffic may be less than many would believe, the tunnel trade has therefore emerged as an emblematic symbol of rebel corruption to many activists in the Eastern Ghouta.

It is difficult to get a clear picture of the tunnel trade, since it is both a military secret and a source of some embarrassment to rebel leaders, while civilian activists tend to avoid the topic for fear of retribution from armed factions. However, the following, rudimentary description is what has been possible to piece together from interviews and information collected in Syrian opposition propaganda, online journals, and on social media.

The tunnel trade takes place in the Damascus suburbs on the western and northwestern fringes of the Eastern Ghouta enclave. After exhausting sieges and years of bombardment, Barzeh and Qaboun, two contiguous neighborhoods located just west of the enclave, next to Harasta, signed separate truces with the Syrian army in early 2014.101 The local rebels were allowed to retain their arms, surrounded by checkpoints of the army and so-called Reconciliation Committees. Municipal workers and state representatives are allowed entry under certain conditions, and the army now generally permits aid deliveries and trade with Damascus proper, though traffic is inspected and sometimes blocked.

This situation is unusual. Most of the so-called reconciliation agreements (musalahat) imposed by the Syrian government on rebel territories have led to the complete dismantling of local insurgent groups and sometimes their evacuation to other opposition-controlled regions, particularly Idlib. Syria’s Minister of Reconciliation Ali Heidar describes a phased process, which according to the Syrian government should ideally move from the ending of active hostilities, to the restoration of services, to full reintegration into the state and government control. In this case, the process has not been completed: “Sometimes we succeed 100 percent, sometimes we do less well. Barzeh is still at the second stage of the process, I would say.”102

One reason for this slow progress seems to be the relationship between Barzeh and Qaboun and the Eastern Ghouta. Government officials, former rebels in the truce areas, and active insurgents in the Eastern Ghouta enclave all profit from the trade flowing from Damascus through Qaboun and Barzeh to the besieged territory. Though neither side is truly content with the arrangement, all have a stake in seeing it continue and individual commanders seem to be making good money from it.

The dividing line between the Eastern Ghouta and the area covered by the Barzeh truce is the Damascus-Homs highway.103 In this area, a major semiofficial point of access has been established, variously known as the Zahteh Tunnel, the Central Tunnel, or the Harasta Crossing. Like the Wafideen Crossing, it allows the Eastern Ghouta to tap into the markets of Damascus, via the truce zones, though that trade is ultimately regulated and limited by the checkpoints surrounding Barzeh and Qaboun.

Starting in 2014, the Eastern Ghouta insurgents also began to dig several smaller smuggling tunnels to Barzeh and Qaboun, as well as to the semi-isolated frontline neighborhood of Jobar, which juts deep into eastern Damascus. These tunnels mainly focused on bringing in ammunition, fuel, and other goods restricted by the government, and on moving wanted individuals and armed units past army checkpoints. Many tunnels have been dug exclusively for military purposes, but around three or four, aside from the Zahteh Tunnel, are used partly or exclusively for commercial purposes. In addition, there seem to be smaller routes, perhaps appended to the main ones—descriptions are unclear. Most of the commercial trade moves along the Harasta-Barzeh route, but tunnels also connect the Eastern Ghouta neighborhoods of Zamalka and Erbeen to Barzeh and Qaboun, and to the military front in Jobar.